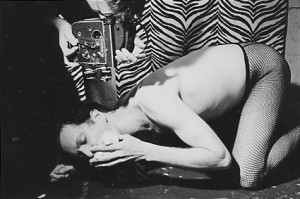

Mike Hoolboom’s feature-length film House of Pain (1995) is a suite of stories that turn around abuse, scatology and bizarre manipulations of bodies. In Precious, Kika Thorne plays a woman who fucks the earth in a cemetery, finds a magical eye, and bathes her face in urine. In Scum, a married couple played by Charles Costello and Janieta Eyre use their own shit to play out a dynamic of alienation and self-loathing. In Kisses, Paul Couillard and Ed Johnson enact a game of sexual torture and revenge, ending in a frolic at a playground. And in Shiteater, Andrew Wilson transforms himself into a magical being who, along with other morning rituals, generates a vast amount of (fake) shit and stuffs it into his mouth. Audience members at the premiere screening of House of Pain demanded to know why Hoolboom had made such a shocking, ugly movie. But they also acknowledged its beauty, at least at the level of the film’s richly textured, black-and-white surface.

Mike Hoolboom’s feature-length film House of Pain (1995) is a suite of stories that turn around abuse, scatology and bizarre manipulations of bodies. In Precious, Kika Thorne plays a woman who fucks the earth in a cemetery, finds a magical eye, and bathes her face in urine. In Scum, a married couple played by Charles Costello and Janieta Eyre use their own shit to play out a dynamic of alienation and self-loathing. In Kisses, Paul Couillard and Ed Johnson enact a game of sexual torture and revenge, ending in a frolic at a playground. And in Shiteater, Andrew Wilson transforms himself into a magical being who, along with other morning rituals, generates a vast amount of (fake) shit and stuffs it into his mouth. Audience members at the premiere screening of House of Pain demanded to know why Hoolboom had made such a shocking, ugly movie. But they also acknowledged its beauty, at least at the level of the film’s richly textured, black-and-white surface.

What does it mean that a film that depicts appalling scenes of torture, shit-smearing and the abuse of objects is beautiful? I don’t the ink the shock value of House of Pain is a question of épater le bourgeois, even if such a thing were possible nowadays. For one thing, there is a simplicity to the way the film presents its scatological scenes. This was not the deadpan, can-you-take-this shock value of rather adolescent films like Gregg Araki’s The Doom Generation (1995), Todd Verow’s Frisk (1995), Bruce La Bruce’s Super 8 1/2 (1994) (which succeeds for other reasons) or Rico Martinez’s Glamazon (1993). In House of Pain the simplicity seems more like innocence, the way a child does things before knowing they are supposed to be right or wrong.

The four stories are organized symmetrically. In the two middle films, couples find some sort of catharsis only after wallowing in abjection so extreme that they would to dissolve as separate individuals. The framing films have an air of redemption and peace, and both end with the figure walking on the beach or into the water.

Also, both characters in the outer films use strap-on dildos-stunningly large, smooth, elegant abstractions; in the inner films, fucking is done with real penises that bear no comparison. This seems to be a comment on the insufficiency of representations of masculine sexuality, if not the worlds-apart difference between penis and phallus. Kika Thorne’s ‘angel’ fucks with her strap-on and comes, even generates (she fucks the ground, then finds a magical eye in the hole she has made), with a sex that seems comfortably borrowed, seems to fit her well in House of Pain’s alternative universe of sexual endowment. The character Andrew Wilson plays transcends his sex: he erupts in other ways, defecating profusely and, with subtle eroticism, breaking a raw egg in his mouth, but like the woman of Precious, he comes only through a dildo.

By contrast, biological male sexuality is punished in House of Pain. In Scum, each member of the estranged couple finds an alternative erotic object. For the woman it’s a bicycle, which she caresses and makes love with, in a tender, visually lyrical scene where the shapes of the bicycle echo the lines of the woman’s moving body. For the man the erotic object is a cauliflower. It is extremely painful to watch him cut a hole in the cauliflower, widen it only a bit with his finger, and painfully fuck its hard interior with his real penis. (The subsequent show will make me skip those dip-filled vegetables at parties from now on.) And in Kisses the engagements between the two men are more like rape or torture. The man played by Couillard undergoes horrible torments, beginning where the camera discovers him sobbing on a seemingly endless pile of concrete rubble, then finding worms and greedily eating them, and continuing to the scenes where the other man tortures him.

Couillard co-wrote this scene with Hoolboom. Not only is Hoolboom willing to devise scenes where male characters can be humiliated (which easily extend to the director himself) but so is Couillard, who plays the most put-upon figure in the film. Perhaps it is at the level of writing that the consensus takes place, the agreement to accept pain and humiliation. It doesn’t happen in the film itself: the woman in Scum violates the man while he is sleeping; the second man in Kisses fucks the first man when he finds him lying unconsciously by the train tracks. These are not depictions of consensual S/M bedroom behaviour; this is not a movie about S/M. The characters break the rules; they represent something out of control.

Certainly House of Pain is organized around sexual subjection, domination and transgression. But these seems to be means of expression for something else. The characters sleepwalk through scenes, as through they achieved some state of grace—Hoolboom does call them ‘angels’ in the credits. There’s an experimental, neutral quality to the scene, for example, where the woman of Precious urinates in a pail (and a sculptural fascination with the way the urine sprays from her shaved genitals) or the scene in Scum in which the ‘husband’ smears excrement on his chest. I have to say that this aestheticizing attitude on my part might be a strategy to deal with extreme images. But Hoolboom’s own approach stresses that these images are not there just for their narrative value. House of Pain is an expressionist film, pushing explicit and violent sexual imagery to a certain limit the same way an abstract painter breaks the codes of painting. Hoolboom shot and edited most of the film in a way that works against the eroticism of the sexual scenes, fragmenting and abstracting them. But this style brings another sort of eroticism into the image. There’s a scene in Kisses where the ’victim’ turns on his aggressor, binds him with wire, and shaves his head: it’s shot in a very dark room, and their struggling figures glow and reflect in the darkness. In Scum there’s a beautiful shot where the ‘wife’ is bathing, and the harsh contrast and high exposure almost solarize the elegant line of her body and her lovely face.

The four stories are too specific to be read as allegories. The scene in Scum does not seem to be an iconic shit-smearing scene, if you can imagine such a thing. The pieces of shit are small and fibrous; when he rubs it on his chest it catches in the hairs. There is too much detail for the scene to remain in the mind as an icon of transgression. Detail complicates an image, polluting it with other ideas, suggesting that to put a simple reading on these scenes would be missing the point. In Kisses, the two men kiss, suck and drink each other through a curtain with a slit in it. The curtain is zebra-patterned. This groovy visual distraction makes me start thinking about why the wall might be zebra, instead of reflecting on the erotics of domination or whatever.

Earle Peach’s soundtrack also forecloses on any sort of iconic quality for the film. In Scum and Kisses the music draws a lot of attention to itself, changing dramatically with each short scene. The music seems to be most successful in Shiteater, where instead of changing every minute it maintains a growling, eerily modulated chord throughout. Like the music, the exaggerated sound effects-the juicy noises of fucking the sloppy sounds of shit, the irritating sound of a zipper being pulled up-perversely underscore the fact that this is a film, an experimental film. Or, again, maybe it’s me who disengages form the film at these points. In my notes taken in the dark screen room, the expert detached criticism gives way to “ICK!!!” in more than one place. An image that is just bearable to watch becomes unbearable for me when sound is added.

In its search for an intimacy that braches the body’s boundaries, it’s interesting to compare House of Pain to Frisk, which was also at the Toronto International Festival. Like Dennis Cooper’s novel on which it is based, Frisk takes the rather densely literal approach that the best way to “get inside” another person is to cut them open. It’s like a bad joke on the idea of visceral knowledge. House of Pain seems to be more about finding a state of grace within, or despite, one’s own body, a state that can only be achieved by taking bodies to extremes. The film touches on a deeply sad, inexpressible longing. How can we live inside these bodies? Can our bodies express truth or love? The ordeals the ‘angels’ endure test the limits of self-coherence and the possibility of survival, with love or self-love intact. When at the end of Precious the woman walks into the light on the beach there is a great sense of release, of having purged some demon. I think this feeling of overwhelming longing is the quality that attracts viewers even when we cannot bear the scenes depicted.

Ultimately House of Pain uses the material of film itself to express what it means to get inside another body. The high-contrast film turns everything depicted into an enormous landscape: the elaborate fabrics and laces the woman wears in Precious, for example, become a world of texture that blends with the woman’s own skin and the grass and sand behind her to make an entire consistent skin on the surface of the image. Frequent close-ups and shots in enclosed places also pull the viewer into a place where she cannot distinguish near and far. Hoolboom’s camera (and film stock) have an obsessive desire to bring what is far near, so that the image itself becomes like skin opening onto skin. It is not a voyeuristic kind of looking-at least, the explicit stuff is shot in a way that seems just as interested in shadows and forms as in the actual shit, cocks, etc.—not a desire to subject things to vision, but to dissolve vision in the things erupting before it. House of Pain creates an intimacy that is less like getting inside a body than like turning the film itself into a quivering skin.