Text commissioned for the Montevideo Catalogue, 2005

Mike Hoolboom is a Canadian filmmaker who since the 1990s has received an international reputation within the fringe media world for his extensive and varied oeuvre. For years worked on 16mm film (of which most have been destroyed) and switched to video in 2000.

His films often contain an enormous amount of processed film and video images that we may or may not know from our collective, virtual archive of images that is daily supplied and corroded by film and television. The work of Hoolboom seems to engage a battle with the overproduction of images as well as their vanishing. Production and memory form a recurring theme in his movies, along with the body, desire, illness and loss. Politics, personal philosophy and experience, quotations and writerly texts, images that come from everywhere, abstractions as well as intimate portraits, are fluently and playfully interwoven.

Our movies mark the passage of time. They are time machines built for mourning and in some moments they are much of what stands between us and our need to obliterate everything, our need to begin again, to wipe the slate clean. There are two kinds of terror here, the terror of annihilation and the terror of remembering. Which will we find more painful? Or more seductive?

Panic Bodies

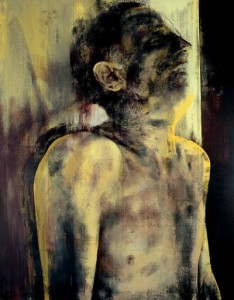

Panic Bodies consists of six parts or chapters, varying in length and style. Each suggests a new approach to these returning questions: what does it mean to have a body; to be a body, and what does this body want? Hoolboom appears in the framing chapters, and in between others take his place, submitting their bodies to a probing research. The treatment and effects of AIDS reform these subjects, but also the sexual body with all its desires and questions, and the almost dying body that can temporarily leave the world to be absorbed by what is called ‘the white light’ in Eternity.

Voice-overs and intertitles alternate and speak sometimes in loaded (quoted) words, and then again in casual little lines like: “I am writing these thoughts because they relate to that moment in my kitchen when we speak and what happens to us.” This intimacy is typical of Panic Bodies. The voice speaks directly to the viewer, confessing, admitting, raising questions.

A theme that recurs over and again in Hoolboom’s work is: looking and being looked at; how we are using images, how images are using us and how our memory is mediated by all this. In Panic Bodies Hoolboom joins questions from and about our body and our relationship to our death, to issues of memory and the image.

Panic Bodies’s opening chapter, Positiv, shows the filmmaker in a small enclosure, speaking about becoming a body and AIDS. Around him three accompanying screens fill with the manic refuse of the mediaverse, providing counterpoint and juxtaposition to the flow of language. The second chapter is a wordless psychodrama, entitled A Boy’s Life, which shows a man in search. Beautifully photographed in close-up, this haptic quest narrative is shot from inside the body, out into a world which it also imagines as a body. The third chapter is entitled Eternity and features a video letter which appears over barely visible pictures made in Disneyland. The letter is by Tom Chomont, subject of Hoolboom’s next movie, and relates the death of his brother, and the white light which accompanies the beginning and end of life. The fourth chapter 1+1+1 is also the shortest, a stop motion romance repeated three times in successive waves of legibility, as two battling lovers arrive at a place where the Other becomes visible. The fifth chapter is entitled Moucle’s Island and features Vienna avant filmmaker Moucle Blackout. It rhymes her movements with the gestures of a small child, and then projects her into a dreamy sexual reverie. Each of the first five chapters might be read as portraits and these are drawn together in the concluding chapter, Passing On, which is the longest and most elaborate chapter. Elegiac in tone, the filmmaker returns to host a succession of vanishing friends and familiars in an avant-garde home movie that is also a ghost story.”

Tom

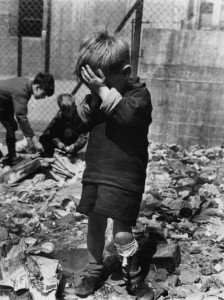

This film leads us through an underworld of long forgotten images, of dreamlike moments that seem to become accessible only in a state of hypnosis; stored fragments of a youth and origin that we might be sharing with everyone else; a collective cinematographic memory of early years and imaginary landscapes of past futures. Tom is an ‘experimental’ documentary almost entirely made out of found footage, from unknown archival material to a famous Buster Keaton scene and from Hollywood to the work of Tom Chomont who is the subject of this movie. Chomont is a well known member of the New York underground scene, a filmmaker, a notorious video artist and narrator. In his film work Chomont tries to reconstruct moments of his past, to give them a shape that can be shown and shared.

Chomont’s recountings are accompanied by a dazzling amount of pictures. This fragmented and unusual biographic construction expresses how liquid and layered a life story can be and how filled up our stories are with images that come from everywhere. Tom speaks about his youth, the relationship with his brother, of love, of his illness with AIDS and Parkinsons. He says that the pictures you make and fill rooms with (pictures of countries, animals, stars and neighbors) changes the image of your own face.

Hoolboom shoots Chomont at home, among mutual friends and walking along the streets of the most photographed city of New York. Intimate moments alternate with archival images of streets filled with traffic and crowds in a city always under construction. It’s a movie about a beginning and a fading life, and about a fragile body weakened by illness. At the same time it is a liberating free fall in which air, height and water play an important role, next to numerous feature film fragments in which doors and windows are opened over and again leading to new rooms and discoveries. Hoolboom’s themes, such as cinema, history, memory, the body, (homo)sexuality and loss, come together in a dark and light, dense, fluent and tender portrait of a man, a time, a place and a state of existence.

Imitations of Life

The structure of Imitations of Life can be compared with Hoolboom’s earlier movie Panic Bodies. Both consist of separate chapters connected to an overall theme and title, which this time is: the imitation of life. The returning question is why and how we represent ‘life’ in pictures, in film and in our memories, and how memory and media influence each other. Moments which are recorded are pictures relegated to the past but pointing towards a future, ready to be seen later. They are already busy conjuring a future of visibility out of the frames of the past. Thereby past and future converge in our tendency—which is related to a compulsive will to remember and to imagine—to imitate what is lifelike. The question is: what is true to life, and how do we recognize it?

Imitations suggests that the shape of our memory is delivered by the pictures that surround us. Each of its ten chapters suggests a way to negotiate this troubled inheritance. This sometimes take the form of a fable or a myth, like in Portrait’s reworking of the Lumiere brothers’ footage, or Secret’s foetal creation tale.

In the episode Jack Hoolboom portrays his nephew, a curious and animated young boy for whom everything is starting. Jack functions as the film’s guide and emissary. The images which surround him are his inheritance. Sentences uttered by Jack are ingeniously interwoven by Hoolboom with quotes and his own texts, so that we—not unusual in his work—never know where the words actually come from. They can sound loaded, like famous aphorisms or poetry, and yet, because they pass so casually and are rhymed with more banal remarks, it never becomes too heavy. The same might be said of the stream of images which arrive from feature films, documentaries, video clips and from his own film and video material. The combination of images makes the whole accessible.

Imitations summons pictures as evidence and storytelling fragments in these essayistic briefs. It moves from the portrait of his nephew to the wordless aquatic epiphany of Last Thoughts which simulates the rush of pictures in the last moment of consciousness. After this ending the movie begins again with Portrait, a relook at cinema’s origins, and then Secret tells another pre-birth tale from the point of view of a foetus. In My Car, The Game and Scaling narrate the trials and betrayals of growing older. Imitation of Life is the longest and most complex of the ten chapters, a meta-science fiction movie whose long picture/intertitle collages are set against personal musings on an empire of movies. The movie concludes with Rain, a slow motion reverie which voices the hopes and regrets of adults who have grown into the pictures which awaited them as children.

Hoolboom plays virtuously with language, text and image, and lets the viewer reconstruct their origins and meanings. By using pictures that already exist and adding other images next to them, he gives them a new context, in order to destabilize their fixed meanings and the empire of imagination. In their new configurations they tell another story. Owing to the density and speed of presentation Imitations of Life requires each viewer to produce an individual journey.

Public Lighting

Memory is also a function of personality, and its staging shifts according to personal inclination. But the personal is bound and mediated by the images which surround us. Sometimes images can take away the sight of one’s own face, or a whole life’s story can be reduced to a single frame.

In Public Lighting six different life stories are on offer as personality types. As in Panic Bodies and Imitations of Life, Hoolboom works in separate chapters. In the case of Public Lighting there is an introduction, Writing, in which a writing narrator formulates with hesitation thoughts six different kinds of ‘personality’ that follow in the next stories and contemplations. Each story demonstrates a different mode of public display (of staging interiority) and uses different formal strategies to enact them.

In the City utilizes layers of superimposition while a man we don’t see narrates a series of break ups in 26 alphabetically arranged restaurants.

Glass is a portrait of the composer Philip Glass, using archival footage of New York.

Hey Madonna shows a fan letter scrolled over her video clips.

Tradition tells a generational tale of forgetting and repetition, set on two continents.

Hiro is a wordless psychodrama about a photographer haunted by atomic memories.

The closing chapter Amy portrays a woman recounting her childhood in which she has been photographed by the same man over and over—she can only look at herself the way he looked at her then, and the way we are looking at her now.

Once again Hoolboom combines his own film material with found footage, clips and icons, interweaving texts and voice-overs. These portraits (which are sometimes city portraits as well) and meditations each represent a way of being, of recounting and of telling. Each perspective is also a retrospective. The past is derived from a domain of pictures, which on the one hand don’t belong to the subject, but on the other hand provide their roots of memory and subjectivity. They are spoken by language. Their personalities are apertures for external pictures and sound.