original program notes for Portugese Cinematheque screenings

Mike Hoolboom is the author of an extensive body of film work (he made films for many years, now he uses uses video, but for convenience we will use the term “film”), in the field of so-called experimental film (another phrase of convenience). Like many experimental filmmakers and videographers, Hoolboom has been the recipient of many exhibitions and installations. It was precisely on the occasion of an exhibition currently underway in the gallery Solar in Vila do Conde (aptly titled Imitations of Life), which brought Hoolboom to Portugal, and permitted these two sessions of his work at the Cinematheque. Besides being a master in the visual domain, with an acute sense of the meaning of each image, which even most traditional filmmakers do not have, Hoolboom has also mastered the written and spoken word. He is the author of hundreds of articles, two books of interviews and another book of film scripts, as well as public presentations which are extremely poetic and models of intellectual clarity. As Matthias Müller, a well noted cinematic artist of the same generational constellation put it: “To his great visual intelligence, translated via the force of the images of his films, is joined a considerable literary talent. In the voiceover narration of his films, Hoolboom uses language that is alternately straightforward and poetic. It is a warmly evocative voice, but at the same time insistent, oscillating between melancholy and sweet irony, sarcasm and brevity, the texts maintain a wonderful balance with the images.”

Imitations of Life is the mature work of an artist who deploys forms short and long, reconciling formal precision with personal statements and innovative material strategies. These personal statements almost alway presents an awareness of mortality — his own and others — but without morbidity or self-complacency. The work arises out of, and in response to, the flood of images in which we live, an endless and uncontrollable epidemic. New technologies have made it very easy, very cheap, and almost mandatory to produce and receive an ever greater flow of images, resulting in a tsunami of amateurism in the field of visual arts. More than ever, Fernand Léger’s observation is valid, whereby a worker and an artisan never delivered a piece before it was completely realized, while too many artists today are content with unfinished work. At present, the audiovisual field swarms with lazy, unstructured works, whose directors are driven by a primary narcissism, clearly convinced that their forms should be free of structure or hierarchies, which is not the way to think – that the initial gestures of production are enough to insist the work should be shown to others and in public, preferably for free. The work of Mike Hoolboom is exactly the opposite. He reflects on what is shown, and on the presence of images in our lives. He is a meticulous craftsman in love with the way and the material, always engaging the spectator, leading him by the hand through the intricacies of an affective perception. The balance struck between the emotional and the intellectual that Hoolboom conjures so often is what makes the work so beautiful, so striking and so indelible.

Imitations of Life is a film about the fundamental importance of images in shaping our personality and our memories. This work is another chapter that shows how “The work of Hoolboom seems to engage a struggle with the overproduction of images as well as their vanishing,” as the Dutch writer Esma Moukhtar so well observed. Like many contemporary artists, Hoolboom’s Imitations of Life works with heteroclite images: excerpts from classic movies, family albums, found material, current films, scientific films, images of early cinema. These various materials are placed in another context, and these amendments are gathered via the look of the director, who before becoming a director was a spectator. Hoolboom reinvents the roll of director as spectator, in other words, as our neighbour. In the introductory text of the abovementioned exhibition, Hoolboom wrote: “It was Andy Warhol who said that movies make emotions look real while in real life they seem distant. Films seem to me at least as real as my friends, and as a filmmaker I am happily consigned to meet them again and again.”

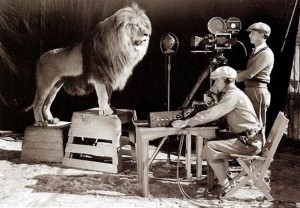

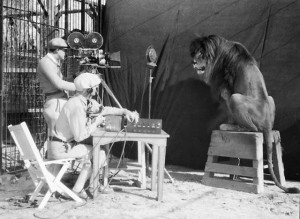

With humor, Hoolboom opens and closes his film with two of the most famous images of opening and closing in the American classic film. Imitations of Life opens with the roaring lion of Metro (but with the sound reworked to make him stutter) and ends with the stuttering cartoon of Porky the Pig announcing, “That’s all, folks!” These are certainly two of the oldest cinematic images that have lodged in our retinas, which connects to the following observation of Freud, cited in the director’s description of the film. “Our childhood memories show us our earliest years not as they were, but as they appeared at the later periods when the memories were aroused. In these periods of arousal, the childhood memories did not, as people are accustomed to say, emerge; they were formed at that time.”

The work’s title is an obvious allusion to a classic film by Douglas Sirk, modified by the addition of the final “s,” rendering it plural. All of these images, all of these imitations of life that engender further imitations, work in a game of mirrors; they are literally our reflection, they have formed our worldview and our memories. At one point, Hooboom specifically mentions the notion of the Lacanian mirror stage, the moment when a child recognizes his reflection, his presence.

But fortunately Hoolboom did not recast his movie as an analysis, this is much less pedantic, not at all the demonstration of a thesis. The ideas flow from the material instead of being imposed on it. Imitations of Life constantly passes from the sphere of personal experience to the collective, following a stream of autobiography and dream. It is divided into chapters, each an autonomous whole and linked together into a larger structure, indivisibly. Like any great movie, this is a journey that seeks to find the future in the past, where we find the memory of what was. In a poignant episode titled Jack, the second longest of the film, which accompanies his nephew during the first years of life, this child becomes a recreation of Hoolboom, and of all of us. The filmmaker is looking for an imaginary past in order to reflect on a possible future, in pursuit of a primordial look, “a second chance.” But we know that second chances are only too rare, and the final segments of this beautiful movie work quietly, with a grave elegiac quality, acquiring the aspect of a dream. Like a dream, we do not control these images, all we can do is wake up.