Some Thoughts on Compositional Strategies in the Works of Duke/Battersby, Mike Hoolboom, and Dani Leventhal

The four artists whose work is featured in the current Hallwalls exhibition — or, if you prefer, the three “artistic units,” since two of the video-makers work strictly as a duo — employ the tools of their chosen medium in highly divergent ways. The team of Emily Vey Duke and Cooper Battersby employ both storytelling and somewhat primitive animation in order to interrogate aspects of the human experience that are often left simmering within the unconscious. Mike Hoolboom’s recent work, most of which has met the viewer at the rather reassuring feature length of 70 minutes or more, has engaged in a kind of multi-perspectival portraiture, refracting both its chose subject(s) as well as the very notion of identity. And the relatively short videos of Dani Leventhal are characterized by a radical condensation of the quotidian, with material that would conventionally be considered diaristic rubbing shoulders with theatricality and aestheticism, in compressed editing schemes that foreground movement and gesture, color and shape, over traditional denotative content, much less exposition.

Any attempt to consider the work of Duke and Battersby, Hoolboom, and Leventhal collectively must absolutely attend to the substantial differences between the artists and their work. At the same time, one should not become so fixated on local, surface differences that we might miss larger, more global commonalities, should they exist. The Russian Formalist critic Viktor Shklovsky proposed that all artworks, and indeed all oeuvres, possess an aesthetic “dominant,” a primary formal gesture which is the organizing principle around which all other elements in the work orbit, like a nucleus. Clearly, within each of the pieces I will be discussing below, there is a different dominant, a specific aesthetic sensibility and approach at work.

However, if there were perhaps one global commonality among these four artists’ work, it would be the tendency, or even the ethic, of negotiating difference within the boundaries of the text. Each of these works is a kind of charged field which, due to certain non-absolute but nonetheless recognizable parameters, permits the organization and holding-in-tension of diverse informational streams. This can mean a set of discrete but interrelated biographies (Hoolboom’s Public Lighting), or a collision between animal and human realities (Leventhal’s Hearts Are Trump Again), or even just between text and image (Duke and Battersby’s Here Is Everything). Within each of these works, there is a sensemaking that allows for moment-to-moment relationships — the motility of actual watching — as well as a macro-movement, a broader sense of sweep and drift that carries the larger dominant along, throughout the work, in often imperceptible ways.

Here is one way to think about all of this. Some experimental film and video promulgates a particular shape or reduced set of shapes across its running time (e.g. works by James Benning, David Rimmer, Michael Snow, or even more densely edited works like those of Ryan Trecartin, which bombard to the point of generating a kind of static wall of data). Other works, like the ones we’re considering here, generate their meaning, by and large, by creating relationships between disparate formal and textual elements, generating multi-tiered systems of harmony and/or discord among those elements. Although terms like collage, montage, assemblage, or even bricolage are largely inadequate to articulate the various ways in which Leventhal, Hoolboom, Duke and Battersby compose their videos, they do at least put us in the ballpark, and provide a contrast with the more minimalist end of the aesthetic spectrum.

In the chapter “Synchronization of Senses” from his book The Film Sense, Sergei Eisenstein describes and expands the concept of montage. Whereas many filmmakers and critics, both in his own time and subsequently, have seized upon Eisenstein’s notion of “collision montage” — that is, the extreme articulation between two shots for maximum dissimilarity and jolt, the explosive dialectic within film language operating on cinema’s micro-level — in this text the Soviet theorist makes it quite clear that montage, as an organizing principle, must be active at all possible levels of a film’s composition. He writes:

The general course of the montage was an uninterrupted interweaving of these diverse themes into one unified movement. Each montage-piece has a double responsibility — to build the total line as well as to continue the movement within each of the contributory themes. […] It is naturally helpful that, aside from the individual elements, the polyphonic structure achieves its total effect through the composite sensation of all the pieces as a whole. This “physiognomy” of the finished sequence is a summation of the individual features and the general sensation produced by the sequence (The Film Sense, pp. 77-78).

Eisenstein is speaking very particularly here about the need for sound and image in a film to both echo one another, and the overall dominant. That is, an artist can and should map relationships both on the micro and the macro compositional levels.

So what does this mean for our four artists under consideration? If we can agree that, alongside their considerable divergences, all four are united by a tendency to bring differences into contact, to negotiate difference, through non-absolute but nevertheless firm, identifiable compositional systems, then we can think about them in a number of illuminating ways. First of all, on the broadest level possible, we can think the works themselves together, within this essay and within the context of the show, since their broad differences can, in even more general ways, be navigated.

But more crucially, we can think of the works as “open sets,” and observe the manner in which the artists have given shape and coherence to disparate forms and concepts, drawing relationships without reducing those forms to a single dominant shape. Consider Public Lighting, a feature-length video work by Mike Hoolboom that is as wide-ranging as it is deft and masterful. The tape exists as a kind of macro-biography of a writer (the voice of Esma Moukhtar) who describes her creative process as an urban typology, a form of anthropological openness or listening/processing of the drifting voices of the city. By forming texts based on these borrowed words, the writer (who, incidentally, is a fictional character herself) performs a kind of monumentalizing that she calls “public lighting.” Hoolboom, for his part, begins the piece with a short studio-bound prologue that consists of the pure manipulation of light — refracting a spotlight off a prism, filtering light through the barn doors of a stage lamp, filming the R/B/G spots of a video projector, etc.

So Public Lighting moves from medium-specificity to an entirely different form of reflexivity, a (fake) biography that, it turns out, explains the rest of what Public Lighting will show us. The writer tells us that there are six personality types that comprise the city, and she will present them to us through her work. What follows are six semi-autonomous, experimental character sketches, which we must assume correspond to the writer’s typology. But how? What Hoolboom has done is to concoct a unifying structure that lends coherence to disparate, semi-detachable works. Public Lighting is indeed a “text,” but one that has been organized on its broadest level by a bracketed or parenthetical boundary line.

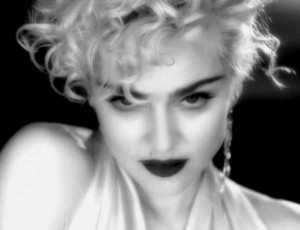

There are six different segments — a man (Ken Thompson) who provides a personal tour of Toronto restaurants based on the dissolution of his relationships; an impressionistic portrait of composer Philip Glass; a recoding of Madonna’s “Vogue” video as a scathing letter from a former lover, a gay man dying of AIDS; a filmmaker (Carolynne Hew) of Chinese descent who has to travel to China for family reasons and experiences temporal dislocation; a noirish portrait of photographer Hiro Kanagawa; and finally, a testimony from a model (Liisa Repo-Martell) recounting her experiences with infamous West Coast photographer Jock Sturges. Each could be a short video in itself. However, each takes on particular meaning within the broader framework of Public Lighting.

In a sense, other of Hoolboom’s longer video works, such as Imitations of Life (2003), Tom (2002), and Mark (2009), share the compositional tendency of sifting and organizing disparate textual materials within an overall framework. Nevertheless, it’s clearly Hoolboom’s strategy to allow the fragments to retain relative autonomy, not to be semiotically determined by their place in the larger work. For example, the writer’s assertion that each represents a personality type may be a Rosetta Stone or a ruse (for the record, I vote ‘ruse’), but in either case it allows Hoolboom to ironize the entire discourse of biographical representation. The individual segments certainly do this in themselves, with their experimental approach that, in the final segments, gives way to explicitly partial, fragmentary knowledge. But raising the very idea that these highly unique portraits could be somehow emblematic of broad social types allows Hoolboom to remind us that portraiture, like any representational mode, tends to lapse into generality the moment it’s realized. We assimilate even the most idiosyncratic knowledge into pre-existing categories; Public Lighting makes this its meta-discourse.

This problem of how to assimilate the radically particular without reducing it to the known is an aesthetic dominant that Public Lighting reinforces even in its most condensed compositional moments. In the segments “Tradition” (on Hew), “Glass” (on the titular composer) and particularly “In The City” (the tour of boyfriend break-ups), Hoolboom edits and layers many images, moving through them not so much with rapidity as with an intensity and force of superimposition and color blending. “Reading” these images is overwhelming, almost painful; our eyes want to either tune them out or fixate on the most prevalent image, filtering the others out. As with the rest of Public Lighting, it is a challenge to remain open and attentive to these dense image skeins, to assimilate multiple forms and apprehend their relationships across different temporal registers.

This is something we can also see at work in the videotapes of Emily Vey Duke and Cooper Battersby, although unlike Hoolboom, they tend to compose with a far more forceful and singular dominant in their pieces. This is because, like a number of other key video artists currently on the scene (e.g., Bobby Abate, Jesse McLean, Shana Moulton), Duke and Battersby are writerly, character-driven artists who tend to organize their tapes around a textual baseline. Nevertheless, this does not inherently reduce the multiplicity or disparate tactics or approaches that their videos contain. Within the seemingly solid organizational flow of script-driven exposition, Duke and Battersby adopt an episodic compositional model that, while not exactly modular, certainly permits the surprising introduction of material that is not “necessary,” strictly speaking, within the parsimonious economic logic of traditional narration.

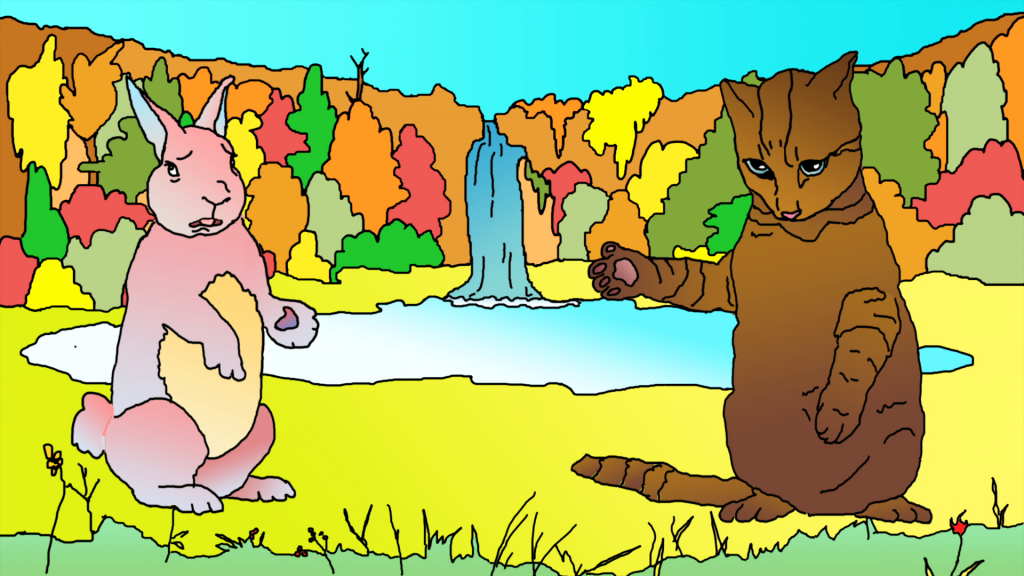

Recent works exemplify Duke and Battersby’s porous conception of narrative organization, whereby multiple registers of information are drawn together as a constellation on the dominant theme. Beauty Plus Pity (2009) introduced live-action material, including (faked?) documentary footage from a deer hunt, and combined it with an original song and animation. All provided different perspectives on the primary idea of human/animal relations, in particular of hunting as a surrogate form of bestiality. The flipside in the “animal love” diptych, Lesser Apes (2011), was constructed as a more complete mock-doc, in the form of testimony/confession from a primatologist who had entered into a love-and-sex relationship with a bonobo. Once again, Duke and Battersby combine childlike singing-storytelling (a tone pitched somewhere between Barbara Manning and the McGarrigles), their own unique, coloring-book form of computer animation, and the intrusion of secondary voices, to provide a multi-vocal, mini-treatise on the value of perversion. As with Beauty Plus Pity, Lesser Apes is script-controlled, but this hardly accounts for the fragmentary character of the tapes, or the ultimate ambivalence of the pieces with respect to human/animal relations and the question of free will.

Their latest work, Here Is Everything, represents a natural progression while also marking a logical separation. If, following Eisenstein’s injunction, it is necessary that every element of a work should communicate with every other, Duke and Battersby achieve this through unusual means. This video announces itself, quite comically, as “a message from the future” from two helpful travelers, a bunny rabbit and a kitty cat, who have come to explain everything to us wayward humans. Although this is a joke, the artists use this frame much as Hoolboom did with Public Lighting, but even more directly, as a kind of filing system for organizing and assimilating otherwise divergent modes of information. The “hosts” exist in Duke and Battersby’s trademark animated mode, but other segments contain rack focus images of plastic figurines, extreme close-up photography of various insects, and not one but two musical numbers. The first song about “the gutter” is accompanied by a long, tracking shot along a mud bank filled with meticulously arranged detritus (a flattened 12-pack of Molson, a Blockbuster card, snipped buds from exotic flowers). The shot looks to be a direct allusion to the creekbed tracking shot in Tarkovsky’s Solaris; we can add cinematic allusion to the types of material Here Is Everything works to accommodate.

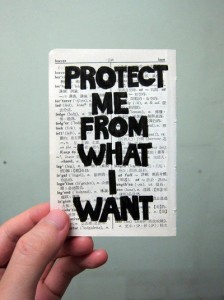

Ultimately, what unifies the piece, its dominant, is its play between exhaustive cataloging of human experience, which it promises, and the fact that it hardly comes close. There is a rank randomness to the “everything” advice that Bunny and Kitty choose to impart. They begin with topics such as the sublime, addiction, and God. But before long, they are providing particular asides about the need for young women to stop acting “cute or precocious” to try to get their way, or a sudden paean to the tapeworm. On the one hand, this seeming randomness, the narrators’ nonconformity to our present-day conception of what constitute the Big Questions, is entirely in keeping with a future perspective to which we are not privy. On the other hand, it is a compositional method that allows Duke and Battersby to dodge and weave in unexpected directions and, perhaps more crucially, to work with various classes and textures of material. Here Is Everything, in a sense, fails to deliver on its promise. And yet, as a broad organizational rubric, it is right on the mark. There is virtually nothing that Duke and Battersby might produce in the future that could not, in principle, become a part of Here Is Everything. Hypothetically, it could be for them what the Magellan Cycle was for Hollis Frampton, although one suspects their restlessness will nudge them onward to the next piece, and the next.

Among the four artists under consideration, arguably none is more in tune with the classical tenets of montage than Dani Leventhal, whose works are breathtaking paragons of economy and precision. In a Leventhal work, meanings really are articulated not just in the collisions between shots, but also in the almost imperceptible micro-gestures that sweep and curl inside of a given shot in order to coax or hurtle it into the next. Leventhal’s editing is absolutely in dialogue with a panoply of avant-garde masters (Brakhage, Menken, Sonbert, as well as her contemporary, Nathaniel Dorsky), but the crucial difference is that Leventhal is a videomaker and as such, her “cuts” have a radically different texture. Their architecture, their very sinew is both softer — there is no absolute segmentation of the frame — and more drastic, electrified, a wholly other optical ordeal. Not for nothing has Chris Stults compared Leventhal’s style with Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty and its phalanx of sensory shocks (Cinema Scope, No. 47).

Leventhal has been working with “collision video” for quite some time, tapes such as Draft 9 (2003) and 54 Days This Winter 36 Days This Spring for 18 Minutes (2009) combine dominant motifs (such as a bike ride as follow-shot, or a study of various dead animals) with nature imagery, portraiture, fragments of daily activities, bits of conversations, all of which are joined on the basis of some similarity or dissimilarity — a rhyming shape, a sound bleed, the flash to a complementary color — that strikes us intuitively, whether or not we perceive it in the time of viewing. Leventhal’s most recent pieces expand on this vocabulary while also edging towards longer sequence-shots, allowing her to articulate certain key events across multiple shots while retaining the pacing and organization that the montage mode permits.

If the more insistently compressed works lend an equal weight, formally and denotatively, to all the material that enters Leventhal’s process-field, then these newer works similarly equalize shot-sequences within the fabric of a gestural, object-driven universe. That is to say, a series of shots in a Leventhal piece which “connect” more obviously than those around them, and even seem to produce a temporary diegetic space, has a qualitatively different effect than those same continuity-producing shots would in a more conventional work. Here, they negate, they press against a general tendency. For instance, Hearts Are Trump Again has what we might in another context call a “café scene,” one whose placement toward the end of the video and instigation of a dialogue relationship might imply that it is somehow summative for the piece. In a German setting, a friend tells Leventhal about having been impregnated by a sperm donor. “Did you pay him?” Leventhal asks. “No! Why should I, Dani? It was just some sperm.”

It is easy, in context, to link this conversation (real or fictional, we do not know) with another extended shot at the midpoint of Hearts, in which Leventhal shows us pigeons entering and exiting a broken warehouse window in close-up. Leventhal’s framing makes this co-opted nest into a kind of membrane through which the screen itself is penetrated by fidgety natural “forms,” and they retroactively take on the character of bobbing sperm trying to fight their way to the egg. Nevertheless, Hearts contains just as much movement through other, less directly legible spaces, both visual and sonic, whose organization and valence is formal above all else. In particular Leventhal employs sharp cuts on sound in this piece, showing musicians playing only to cut them abruptly off.

Hearts Are Trump Again reflects a slightly looser compositional approach than some of Leventhal’s previous efforts. (The title phrase, spoken by a disgruntled senior citizen playing bridge, perhaps gives a hint regarding the tape’s overall mood.) Tin Pressed is a bit tighter, but similarly replaces the hard, jabbing collisions of Leventhal’s earlier works with a more enveloping, poetic sensibility. As per Eisenstein, Tin Pressed is a piece that rises and falls with motivic gestures on the small as well as the large scale, with bodily shape and movement operating as the aesthetic dominant. For instance, the start of Tin Pressed relies on either a form holding the center of the frame as a nucleus, with action swirling around it (as in the first shot of Leventhal on the concrete, being kicked by unseen assailants, and the second shot of wasps inside a yellow flower) or movement around an empty center (as in the fourth shot, with bait sardines whirling in a water bucket). The subtle shift in orientation created by the bobbing fish takes us from circular motion to perpendicular stasis; the brief fifth shot of a Virgin Mary icon is quickly supplanted by Leventhal’s bare back as she’s mashed into a mammogram machine. This shot, like the extended café conversation in Hearts Are Trump Again, holds for quite a while. Then it is replaced by a side of beef hanging in a butcher shop window.

This very brief video (just under seven minutes) concludes with two unusual shots. One finds Leventhal “editing” within a single shot through a sly zoom-out. We see a woman on a TV screen speaking sign language, pull back to see that she is in the corner, translating an episode of “The Smurfs,” and then see that the TV itself is droning on unnoticed in the kitchen of a halal restaurant where a man slices meat. The final shot, another of Leventhal’s extended plan sequences, is of a Turkish woman singing a torch song in what appears to be a karaoke bar. If we think back to the rest of Tin Pressed, this woman’s plaintive gestures become a bookend to the (pretend) violence against Leventhal on the ground, a more extended form of torment.

Violence, the body, and the submission of oneself to punishment and/or discipline — these are some of the key ideas wending their way through Leventhal’s most recent piece, 17 New Dam Road, along with a dominant concept which, many of us would agree, is related to those others in fairly direct ways: the family. I will be the first to admit to being somewhat baffled upon first seeing Leventhal’s new work, given that it is so stylistically different than everything else of hers that I have seen. It is practically a documentary, in that the shots do not “collide,” but rather work in tandem to depict a single location and those who occupy it.

The piece takes us into the lower-middle to lower-class digs of the Russo family: Jason, Jon and Teresa. A family friend, Jason Albrechtsen, is also present. What we see and hear of them is somewhat jarring. Their yard is filled with garbage, as though cleanup were still pending following some natural disaster. They are seriously into guns. One of the young men is wielding nunchucks, then swinging around on a chain hanging from the ceiling. Who are these people? In time, we discover that Teresa is a boxer, and one of her brothers is seen taking promotional photos of her as she strikes mid-punch poses. This, in essence, is the entirety of 17 New Dam Road. On its surface, the piece hardly feels like Leventhal’s work at all.

But as I looked closer, and perhaps more importantly as I considered the piece not only within the context of Leventhal’s body of work but of this current show and the other three artists heretofore considered, I discovered some points of entry. Not only did 17 New Dam Road open up for me, but the idea of it as a singular video-text began to open up as well. For one thing, I was wrong, plain and simple, not to see this piece as characteristically Leventhal’s. While it is very different, it also represents a logical expansion of the tendency toward extended portraiture sequences and para-documentary already germinating in both Hearts Are Trump Again and Tin Pressed. What’s more, based on the manner in which Leventhal has deployed documentary/interview modes in those works, it is beyond naïve for us to simply assume that our visit with the Russos is strictly on the level. Artifice is clearly a matter of degree, but as Teresa shows us at the end of 17 New Dam Road, there is performativity, a self-conscious presentation of self, at work.

But even more broadly (and this takes us back to questions Eisenstein raised), if we think not about this or that video, but the entire Dani Leventhal master-text, all the videos a part of a grand ongoing project, then how does that shift our perception of 17 New Dam Road? Juxtaposed like a “shot” against the likes of Hearts and Tin Pressed, it is a somewhat lengthy, elaborated rupture, not unlike the café scene or the singer’s conclusion within those single texts. In this respect, Leventhal is creating patterns and rhythms in the composition of her works, between and among shots, and even on the macro-level, between and among individual works. And so, the sensibility that we must bring to any given Leventhal video — being prepared to negotiate difference within a unifying framework — is now the same one we require when facing a new work in comparison to the ones that came before.

What Leventhal, Hoolboom, Duke and Battersby share, then, is a mode of viewer address that requires that we meet the work as an entry into an active field of relationships. A boundary exists, one which defines the kinds of relationships that can and will occur within the works. But those boundaries are themselves permeable (as we see above, they can even spill over beyond the notion of the discrete, singular “text”), and what they actually delineate is a time and space through which we subject ourselves to a set of discontinuities and forge connections, see what we hear, observe minute changes as they accumulate into broader, more global wave forms. The works ask us to synchronize our senses, so that we may better perceive our shattering loss of calibration.