These entries were written by Jean in a number of Visions du Reel catalogues, including the year of my retrospective in 1997.

Mike Hoolboom

This Toronto-based filmmaker sent the video cassette of Letters from Home to the Visions du Reel festival which we watched with a great deal of interest. Mike Hoolboom knew how to captivate his audience, both through a very personal, fragmentary and autobiographical narrative, based on the family, and a visual style which impressed strongly upon the viewer the fragile nature of film and the beauty of the flashes of light and dark over the images. This made us want to examine in depth the rest of his work, which proved to be both abundant and distinctly apart from themainstream. The body of work that we viewed in order to prepare the program was composed of some twenty films ranging from two to ninety minutes in length which were shot between 1980 and 1997. Four distinct features hallmarked these films, which, word had it in Toronto, were the most striking of the independent productions in Canada, or what could termed the Canadian underground.

The first and most easily identifiable of these features concerns the playful and provocative manner in which Hoolboom transforms the images which dominate the market. In Shooting Blanks he edits together an amazing series of sequences from recent films of sex and violence in order to denounce their fundamental inaninity. As for Dear Madonna, he superimposed subtitles over the images from one of her videos, a sort of letter to the singer which lays bare the mechanics of her rarefied eroticism.

Contrarily, in a manner of speaking, the filmmaker cultivates a passion for old films, found footage, and home movies, which he integrates into his work. Of these, Brand is one of the most beautifully shot in which children play in a subtle show of black and white contrasting light and fleeting movements. Of course, these image are also diverted from their primary function, but here the result is not iconoclastic, but rather an imaginative and poetic form of cinema.

As regards genres and themes, Mike Hoolboom’s films lie anywhere between documentary and fiction, a constrant thread running through them being what arises out of close proximity with the subject. When, on the documentary side, he films a friend’s travel notebook in Mexico, he centres his concerns on the body in motion, its confrontation with signs of death, its need to find its roots and shelter. But it is when the filmmaker decides to focus on the exacerbation of sexual fantasies and death wishes which transform bodies into defecating bags of skin that he outrageously fictionalizes his often nightmarish narratives (in House of Pain, for example).

To sum up, Mike Hoolboom is a craftsman in film, busy making films whatever the cost and imposing his truly film-based sensitivity. He extracts from blacks and whites, camera movements, editing and the dynamic relationship between sound, voices, and images, the notes of a strong aesthetic experience through which he exorcises his demons and throws into relief the accursed but nonetheless poetic side of images.

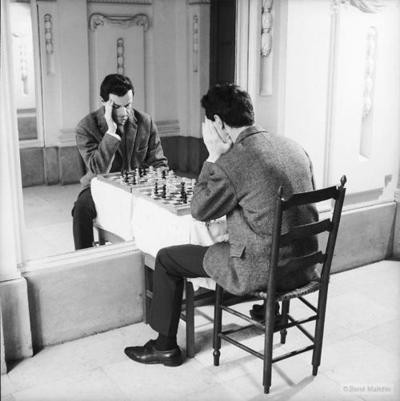

Frank’s Cock (1993)

At the top left, the face of a man in black and white. In front of the camera, he talks about his friend Frank, their homosexuality, their close friendship which death brings an end to. The image is gradually composed of one, two, three other frames (microscopic views of cells, fragments of faces and naked bodies, pornographic close-ups of men making love). With a multiple soundtrack (soul songs, sound effects), Hoolboom disturbs one’s sense of sight and hearing (where to look, what to listen to?) and sketches a portrait by using effects and the juxtaposition of lacunal, arbitary and provocative elements, which are likely to reconstruct memories of the loved one he has lost.

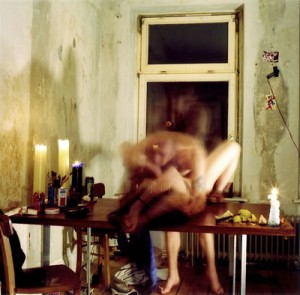

Panic Bodies (1998)

Howling sirens and film which seems to be burning evoke the violence of war. From the ruins of the images, a man and a woman gradually emerge. Without a word but with a powerfully suggestive soundtrack, Hoolboom sets the stage for a strange dry-humoured theatre. Particularly daunting is the role of the woman who ironically delights in doing violence to the man. With its great formal inventiveness combining accelerated sequences and pixilation, this film is as jarring as the lives of many couples.

Moucle’s Island (part five of Panic Bodies)

The film is composed of visual and geometric variations with the oneiric correspondences in the background which seem to guide, as in a nightmare, the paces of a woman whose hand is stretched out towards unattainable horizons. Excerpts from a colour home movie intrude, images of the former innocent happiness of a little girl. Another film with nudies of total and feigned innocence echo the character, whose body is literally tortured by these images highlighting its painful solitude.

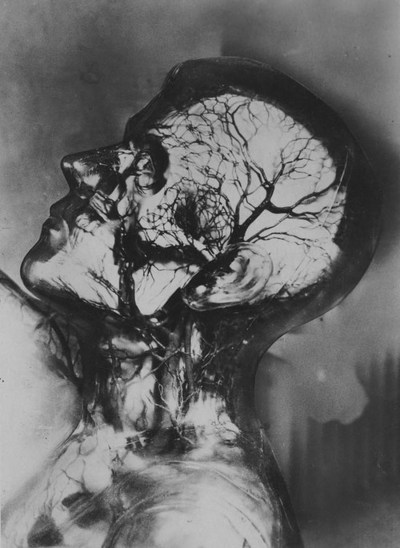

Passing On (part six of Panic Bodies)

Children playing emerge from overexposed film spoiled by time. It is snowing. These solarized images deal with memory in this film of maturity by Mike Hoolboom. The tone is serious; his voice evokes his brother, his parents. The people appear on the screen as though they were disappearing. Hoolboom records the loss of loved ones whose features he stares at with lasting affection. Beautifully simple recurring shots of the white square with black lines crossing it represent the realm of the hereafter, where the ghosts go. With contained and poignant lyricism, Passing On addresses itself to death as something familiar, death which prowls and throws into relief the images of a cinema trying to resist another death, no doubt worse, a white death of memories forgotten, without images.

Imitations of Life (2003)

Mike Hoolboom’s latest work is an extraordinary palimpsest in action. It is packed with cinema images that interpenetrate, fertilize and repel one another. Taken from Hollywood fiction films but also from newsreels and documentary and scientific works, all these images patiently collected against the background of a salutary hold-up (the scenes are excised without any particular precaution from the gigantic body of cinema films, and by extension from the myths that they convey) have something of the construction of a metafilm. This is both a situationist commentary, through the playful and iconoclastic way in which the works concerned are diverted, and at the same time a Sisyphean attempt to get another story to emerge from this magma of images. In ten chapters Hoolboom gives consistency to nightmare-filled sleep and to waking dreams, with which he constructs a political and poetic reflection. Political in that he brands cinema as a colonial weapon, which even today-at least partially-tends to impose an imperialist vision of the world. The documentary shot of two white women throwing a few bread crumbs to some poor people is quite terrifying from this point of view. His film is poetic in its development of associations via editing. The film is organized into periods of harmony and hiatus, where light and darkness, body and decors, draws the arabesques of an incomplete narrative. When Mike Hoolboom himself gets hold of a camera, it’s above all to film Jack, his sister’s little boy, for whom he shows concerned affection.

In an intimate mode, voice-overs express doubts about the history of human beings and their expectations as they face the future. The pieces of music have a very elaborate density. They work at the heart of time, the passing of which they strive to disrupt and the buried dimensions of which they strive to bring out. The passing of time is modeled by images of the world in which Mike Hoolboom’s archaic fears and dreams reside. But it ends with a gag-the filmmaker’s elegant way of not giving in to melancholy.

Public Lighting (2004)

Mike Hoolboom puts together some disparate clips, some beautiful images and hesitant shots from family, fiction, reality archive and advertising films (the Japanese advertisement for an all-purpose cleaning fabric is hilarious). Some images have been found or borrowed while others are original and have been shot for the purposes of the film. In the images there are also words, uttered in short sentences, and the voices of men and women. But this is only half the story. The filmmaker uses a dual approach to images and sounds to construct his unique universe. On the one hand, he gives them depth by slowdown effects, fade-ins and fade-outs, solarization, intermingling of visuals and sound in a complex dramatization relationship. Public Lighting thus consists of strong images that show us the ages of history, its moments of grandeur and shame, touching on the public and private spheres, mingling show-biz and intimacy. An image in a Hoolboom film is always multiple, a confusing palimpsest that is embedded at a certain point in a different image, a pagan icon that keeps trace of the movement of a body, the expression of a face, the inflection of a voice. On the other hand, although this magnificently impure film is based on a very elaborate editing rhetoric, its profound movement leads to uninterrupted mediation.

Public Lighting consists of six portraits which a young writer announces at the beginning of the film. These six people tell of ordinary follies, narcissistic obsessions, demiurgic desires and wounded memories. The separated man, the obstinate pianist, the aging singer, the Chinese émigré, the nocturnal Japanese and the confessed woman are fragments of a collective history. The warm lighting used by Mike Hoolboom illuminates sleepless nights when one is no longer prepared to be deceived—at least for a while-by the ghostly apparitions that haunt our dreams. A single image then appears to emerge. That of a poetic intelligence worried about the world, in which the grave and lucid Hoolboomian hero aspires to some recognition, to a semblance of eternity and to a ‘genuine’ place in the movement of life.

Fascination (2006)

Among documentaries, biographical portraits are a canonical genre. Generally, these strive to stick as closely as possible to their subject, highlighting basic traits that reinforce the viewers’ reasons for holding in esteem-or not-the said subject. Rare but welcome exceptions include Mike Hoolboom’s latest work, which portrays the video artist and performer Colin Campbell (who passed away at the age of 59, in 2001). A beautiful and charming man, Campbell felt driven to externalize his femininity; he would dress up in all the finery of a woman fishing for compliments. As the filmmaker exclaims: “This man-woman, a person who lives in stereo and hence: my first real stereo movie, two channels!”

Nonetheless, it took Hoolboom several exhausting months, even years, to put his film together, implying that he sought as much to capture Colin as to define his own identity. The resulting biography serves as a platform for his autobiographic desire: a demiurgic and compulsive determination to subject film images and sounds to in-depth treatment. His superimposition of the faces and voices of Colin and himself forms a thought-provoking single image, which becomes the film’s icon. In a masterful montage that gives rise to astounding combinations, Hoolboom grapples with his phantasms and imagination, which are reflected in the images he shot and later retrieved from his circle of acquaintances and/or took back (“pilfered” as he terms it) from the flow of the industrial audio-visual production. Hence, Fascination has less to do with Colin than with the utter attention devoted by the filmmaker to the life of the images, thought of as aids to dreaming and dying, forgetting and thinking. Hoolboom reveals how such images belong to the time and space where our collective history settles in layers-a history that is explosive and violent, as well as individual, fragile and abortive. Could we say that Colin dims as the subject figure, beside Hoolboom’s spirited manner of turning the portrait itself into a rhapsody with the hair-raising turbulence of a maelstrom? And that Fascination came into being against the will of its main character, whose portrait the film does-if cautiously-end up piecing together?