excerpted from “Grappling with Israel: From Sontag to Lacan and the Maoists in Between – Jadaliyya (September 3, 2012)

It is thanks to the curatorial competence of the organizers of the London Palestine Film Festival that Mike Hoolboom’s Lacan Palestine may be read as an attempt to visually re-present past interpretations of Israel. Hoolboom’s striking skill in grappling with the birth of Israel in his stunning work is testament to cinema’s ability to deconstruct dominant cultural representations without compromising either political or aesthetic values. It is also a tribute to the world community’s growing recognition that the Palestinian plight is indeed valid, genuine, and justified, and that the call to revise the history of the conflict can no longer be ignored.

Using as a starting point Lacan’s psychoanalytic theory of the “mirror stage” and the “alienation” it results in, which describes the early shaping of the ego in response to a clash between one’s self-perceived ideal visual appearance and one’s actual emotional experience, Hoolboom stunningly juxtaposes the trauma of the ancient Judaic experience against the contemporary pain of the Palestinian one. He hints throughout that while unraveling the layers of history does indeed put in perspective the momentous moments we experience, the moment of trauma when it occurs can never be reduced to mere historical occurrence, precisely because of what are ultimately our “singular” experiences. By stitching together visual imagery already etched into our minds and nestled into our subconscious, Hoolboom probes his spectators to reconstruct the layers that constitute our understanding of nation, community, and tribe. Central to his cinematic essay is the vast archive of visual material reassembled by him into a heart-wrenching story of human pain. Included in this are: epic American Civil War films, scenes from violent Crusader wars, Hollywood productions bursting with orientalist overtones, and even shots from more recent experimental films such as Sontag’s Promised Lands and video art works by Velcrow Ripper, Elle Flanders, and Dani Leventhal, sometimes superimposed over the voice of Edward Said and others. The dizzying pastiche of footage is interwoven with iconic images of Israel’s brutal occupation, such as the Israeli Army’s beating of Palestinians with truncheons dictated by Yitzhak Rabin’s “break the bones” policy in the first Intifada, and the horrifying destruction of Gaza in 2009. Ben Gurion’s proclamation of the establishment of the Jewish state standing under a statue of Theodore Herzl, founder of Zionism, and accompanying street jubilations are also part of the assembled footage. These images then metamorphose into scenes from films depicting the hedonistic celebrations of the Roman Empire’s ruling elite.

A large segment of the film is dedicated to uncovering Britain’s role in the violent inception of the state of Israel. In one sequence, Hoolboom takes his spectators on a journey through the passion, drama, secrecy, and tragedy of the inter-war mandate period. This is done through assembling maps, voice-overs, and news footage, such as that of King Abdullah of Trans-Jordan standing alongside British mandate officials, in a nod to the collusion between both over the carve up of Palestine. Other footage recalls BBC commentary from the inter-war period affirming British interest in ensuring a friendly (Jewish) population on the historical land of Palestine at the expense of marginalizing its original inhabitants (Palestinians).

This dizzying series of images is interspersed more than once with the quintessential British icon of drama and conspiracy: the Rolls Royce “spirit of ecstasy” mascot adorning one car driving freely against a backdrop of an ongoing British imperial pomp ceremony. As if adding insult to injury and in a breathtaking end to the sequence, Hoolboom presents us with a shot of two men, one naked, the other in a British army uniform, locked in a passionate embrace lying atop a Union flag. Hoolboom’s choice of footage here compellingly recalls British PM David Cameron’s suggestion that British aid be cut from those countries with anti-gay rights records, indicating, as sharp criticism warned, a contemporary repeat of imperial Britain’s civilizing mission.

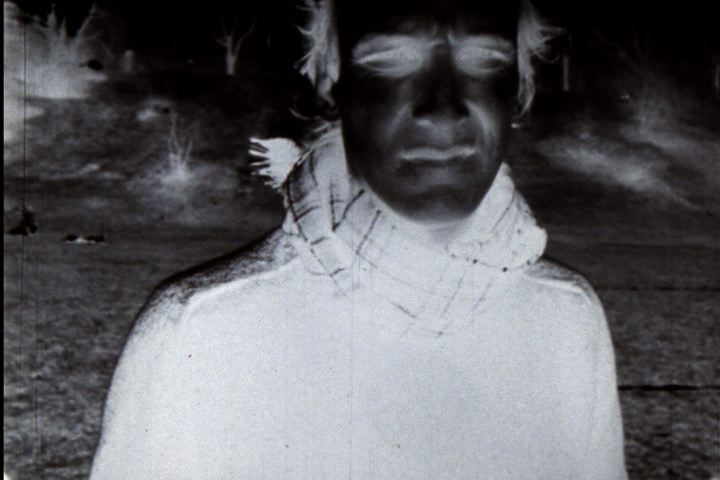

“What are these guys doing in jazz combos?” asks filmmaker Mike Cartmell in a voice-over monologue reflecting on his painful personal life experiences by mapping them on to collective ones. He goes on: “Coltrane, no one could play like that. Elvin Jones, nobody could drive a band like that. Each one of these guys is playing something different, but together there is a coalescing of these quite discreet, quite radically different singular expressions.” There is a mismatch between what the British Empire, and the violent birth of Israel it helped bring in to being, perceive of themselves, and the reality of the “singular” painful experiences they engendered as a result, Hoolboom seems to be saying. His point is movingly driven home through his Lacanian visual interpretation of the manly outer demeanor of a fearful and timid young Palestinian boy woken up in the early hours of the morning by his mother and forced to mount a bus full of adults to see his imprisoned father in an Israeli jail.

Despite what may be interpreted as his collapsing of the collective and the singular into a morass of parity through his choice of visualizing ancient and near history, the sheer brilliance of Hoolboom’s film lies in the fact that he never once loses sight of the reality of the conflict today. Despite never stating it, he is clear on who the perpetrators are and who the victims are in the contemporary conflict in Palestine. He reminds us throughout that history is always part of a living consciousness that pulls together past and present as a way of remaking, reclaiming, and reimagining what we think we already know. And that he does without ever shying away from interpreting the history of a conflict that is in dire need of being re-read and re-told, if it is ever to end.