Montreal Gazette, Feb. 4, 1999

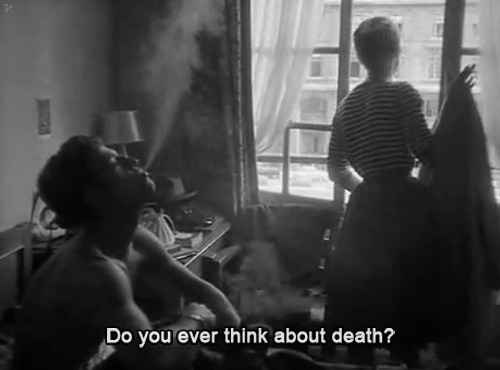

Toronto filmmaker Mike Hoolboom’s Panic Bodies is a 70-minute portrait in six parts about life, AIDS, death and memory and our ultimate corporeal betrayal by time, disease and decay. It is not Toy Story 2 . It is, however a profound reverie upon the impermanence of all flesh and the powerful pull of whatever comes after we have shuffled off this mortal coil. Less feature film than collection of found or retrieved objects, Panic Bodies feels like treasure unearthed in a loved one’s attic after the loved one has left. It is the key to the sanctuary of psyche.

Hoolboom’s most recent opus was three years in the creation and is divided into separate pieces of a whole. It begins with Positiv, a monologue about AIDS told on four screens with images from Terminator 2, science films, Michael Jackson and home movies to name a few. Next is A Boy’s Life, which features T.O. performance artist Ed Johnson, Ed’s johnson, the sins of childhood and the possibility of escape through what your priest called self-abuse. Eternity is a film in the form of a letter written to Hoolboom by a friend in New York about the afterlife. And 1+1+1 follows a couple dressing and undressing against a soundtrack wall of industrial noise by Earle Peach. Moucle’s Island is an all-women daydream featuring Viennese filmmaker Moucle Blackout, while the final segment, Passing On, is an elegiac, hypnotically rhythmic look at family history seen through over-exposed film, as if from a great height, or a greater beyond. It is strange and familiar and almost unbearably sad.

Panic Bodies can make for some heavy emotional sledding and might drive those unused to experimental filmmaking to the wall. But those willing to be carried by it will find the experience fulfilling, fraught with identification and quite unforgettable which might explain why such a theoretically difficult piece won the Telefilm prize for best Canadian feature at the last Festival of New Cinema and New Media here. Great art will out, regardless of content.

Hoolboom isn’t modest about Panic Bodies. He isn’t boastful about it, either. Speaking from his home in Toronto this week, he seems to regard the work as an extension of himself, something he does because he has to. It is who he is right now, in the way that earlier short and medium-length films like Frank’s Cock, Kanada and Valentine’s Day were him in the early 1990s.

“The film represents a lot of work over a lot of time. it was made cheaply, with portraits of people and parts of my life. It’s like a deep and intimate talk between friends before going off to our own solitudes. For me, it’s a way to reconfigure the world and find a shape to everyday life.”

Hoolboom slips into the mystic when he explains that “the finished film exists before I make it. The journey as a filmmaker is to find the place where it is. The piece has inclinations and rhythms of its own. You have to listen to find them. Listening is central.”

He says Panic Bodies and his life in general have been “scrambled together by a combination of doing seminars, getting grants, writing books and living in a rent-controlled apartment,” and cheerfully admits his film isn’t likely to open widely in the multiplexes of the country any time soon. “It’s feature-length but not a feature film�there’s no narrative trajectory. It’s hard to carry around something long, ‘difficult’ and ‘experimental.’ To the extent that I can do it, I become my own distribution company, sending out duplicates to festivals and taking the film places. It’s trundling out into the marketplace at its own steam. One imagines that movies are fixed objects, but I’ve found that it looks different in different places. In experimental festivals it looks mainstream, yet at conventional festivals it seems transgressive. Film itself is interesting. It’s a living, breathing thing. Our experience of watching is really watching the process of film dying.”