Film so good, it ruined my day: Highly personal work looks at the diseased boy and the filmmaker living inside by Mark Caughlin (Manitoban April 7, 1999)

Perhaps the best thing about experimental filmmaking is not so much the startling originality of the visuals, but rather the highly personal tendencies of the form. And when the creator of such films is living with AIDS, the touch of death tends eventually to find its way into that author’s films. Diagnosed as HIV-positive ten years ago, Mike Hoolboom kicked his filmmaking into high gear at the time and, by his own account, repressed everything he could.

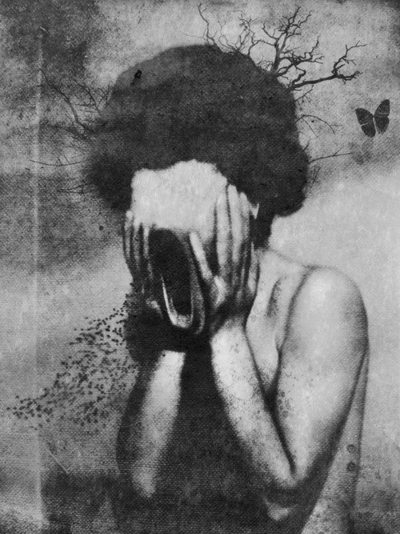

Panic Bodies, however, marks a turn toward a calm, bold candor: it’s a meditation on flesh, on death and on the disease inside Hoolboom’s body. It’s equally a set of hallucinations, an exercise in memory and an elegy to himself that (of course) recognizes his own continuing existence. While the experience of watching Panic Bodies one afternoon left me depressed for the rest of the day, it did so in a meaningful way. The film avoids being emotionally manipulative, making its impact in a way that only a well-crafted film can. Hoolboom may address the audience directly, he may flaunt nude bodies – both healthy and lesion-ridden – but he’s not out for his audience’s sympathy, nor is he out to shock. Rather, he’s groping towards understanding, and he’s sharing that process with an audience. But while he’s considering a whole range of questions besides disease, the body is clearly at the forefront. In the last section of the film, for instance, he contemplates the fact that, as humans, we are contradictory, incoherent beings. Ironically, both our memories and our existence itself are anchored by our body, which is at once our most fundamental imprint, but also the part of us most subject to vulgar decay.

For the filmmaker, film stock is equally the most important imprint – however fragile. In Hoolboom’s hands, it undergoes the same sort of mutation experienced by the body. The Vancouver-based artist shoots new footage and mines home movies and other found images, then processes, blurs and cuts them up, all in order to make things both more personal and more detached and, above all, to re/member. Critics like to highlight the fact that Hoolboom uses footage culled from rock videos, porn and documentaries, but aside from the film’s first section (Positiv), the found image that he uses are not so much pop-culture cut-ups as they are integral – if contradictory – contributions to more extended meditations. And because death doesn’t often come in the form of a dagger in the guy right before the curtain, Panic Bodies broaches its topics idiosyncratically. Divided into six distinct parts varying from 8 to 20 minutes in length, the film comes together in an uncertain whole. In the first segment, the screen is divided into four sections. In one of them a man (Hoolboom himself, presumably) delivers a monologue about AIDS. The accompanying sets of images ironize, (de-)contextualize and expand on what’s being said and felt.

A Boy’s Life, like Moucle’s Island, begins by using the body as a canvas and a mirror, before becoming the story of a man who loses his penis. Moucle’s Island, by contrast, moves into the realm of 20s/30s lesbian fantasia. Hoolboom reduces film stock shot in Disneyland to flecks of light and deep shadows, focusing primarily on sounds of lapping water in Eternity. Over the visuals, he scrolls a letter from a New York filmmaker that talks about seeing the “light” and his brother’s own death. Hoolboom calls his films “documentaries of the imaginary.” As such, this film belongs firmly within the “avant-garde” camp. But it’s not only worth seeing because it’s aesthetically on the edge, arty, or because it makes you think – although it does – but more importantly, because it makes you feel.