Looking for Troglodytes: an embodied rumination on experimental cinema by RL Cutler

(Front Magazine March-April 1999)

December 20, 1998 was a cold and bitter day. Xmas was around the corner and, unusual for Vancouver, snow was on the ground. I needed a diversion, from the December consumerfest and so, on that freezing Sunday afternoon, I made my bundled way to Gastown. I had discovered that Mike Hoolboom’s Panic Bodies would be showing at The Blinding Light Cinema, that fabulous fringe cinema space. I had heard his work mentioned many times by the film buffs and hipsters who populate this metropolis, sequestered in their non-profit offices, or critiquing from sofas from both sides of Main. This was my chance to see the work of a respected, contemporary experimental filmmaker, and I would not let snow, nor sub-zero temperatures get in the way of the experience.

I thought that Mr. Hoolboom’s work would be able to entice more urban troglodytes from their bunkers. But upon entering the theatre, I quickly realized that I was on my own, quite literally, in this crazy peccadillo. Just as the show was about to begin, my solitude and reverie were punctured by another spectator entering the dimly lit space; here I thought was a comrade seeking solace in the comfort of strangeness and cinematic form. But, alas, he belonged to a different breed of troglodyte and left the theatre half-way through the film.

In the introduction to his book, Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada , Hoolboom cities Barthes’ description of leaving the movie theatre: “The subject who speaks here must admit one thing: he loves leaving a movie theatre. finding himself once again outside in the illuminated and half-empty street (somehow he always goes to the movies on weekdays, and at night), limply heading toward some cafe, he walks in silence (he does not care much to talk after seeing a film); he is stiff, a little numb, bundled up, chilly: he is sleepy irresponsible. In short, he is coming out of hypnosis.” Roland Barthes, Upon Leaving the Theatre

Hoolboom interprets this passage as an example of the collective dream produced by the cinema experience, sitting both alone and together in the dark. On this cold afternoon there was no communal experience nor group anonymity within the Blinding Light. Through a haze of hypnosis and somnambulism, Barthes’ Paris facilitated a saunter to the local café. Vancouver’s cold air inflected my own narcosis of reflection, en route to my rental cave.

As the publicity points out, Hoolboom’s film celebrates the complexity of themes addressing the life of a body. “Drawing from sources as varied as hyped-Hollywood, obscure 20s porn, and his own treasure trove of gorgeously shot original footage, Panic Bodies is a complex and visually arresting study of life, love, death, family, obsession and being a stranger in your own skin.” I was particularly interested in the elliptical and synthetic form Hoolboom developed to impart this vision. It integrated a range of techniques and modes in order to describe the complexity of human experience. The hybrid nature of Panic Bodies signals a fusion of past experimental styles into a synaesthetic effect. What appears to constitute contemporary experimental film is a combination of technological innovation, challenging subject matter (libidinal and excessive where possible), and space for reflection. To this end, Panic Bodies can be situated inside a broader consideration of experimental film.

During the last few months of 1998, I accepted the task of teaching studies in Experimental Animation/FilmVideo at Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design. It seemed epistemologically necessary to come up with some definition for experimental film. Not surprisingly, there is no single description for the subject. Its various labels highlight this: avant-garde, poetic, visionary, materialist, formalist, conceptual, fringe, alternative and of course underground. These terms reflect the often heated debates circulating at the time of the film’s initial screenings and they resonate very disparate agendas.

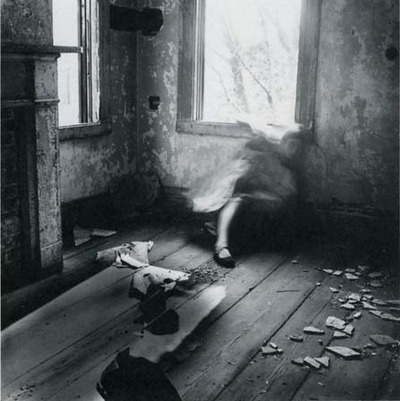

Since film became a cultural product at the end of the last century, experimentation has been central to the practice. Consider George Méliès’ fantastical play with editing and special effects. Although the Lumiére brothers’ projection of still photographs provided the illusion of movement and writing of light, theirs was more of an experiment driven by scientific curiosity. While new technological features have always excited the makers of time-based media, “a horizon line of the real, a line separating the simply visible from the impossible” distinguishes truly cinematic work. The surrealists, progenitors of experimental film, understood the fragmented ontology of moving images which allowed for juxtaposed scenarios and imaginative aesthetics. Maya Deren, with her surrealist and ritualistic sensibility, demonstrated how space, time and illusion were the perfect subjects for film By the fifties, experimental film had been influenced by the progress of modern art, specifically highlighting a self-reflexive and formalist agenda. To those who appreciate the non-commercial, experimental filmmakers can stretch form and content making new experiences for the embodied mind.

Although there is a large and diverse output of experimental film, it is difficult to actually view these time-based objects. While paintings and sculptures take up residence in galleries and museums, screening ‘art films’ is still a tricky venture. In part, the paucity of venues for experimental film is due to problems of funding, distribution, and a colonial unconsciousness. By this I am suggesting a uniformity of cultural and social experience that colonizes the imagination.

What makes films like Hoolboom’s so fascinating is that they do not simulate reality nor the reality of mainstream film but articulate an alternate or parallel consciousness. Many experimental films have imbibed the evolution of film production and employ various strategies or modes of visual experience. Narrativity is fused with the awareness of one’s own perceptions. “Thus one invests the experience with meaning by exerting conscious control over the conversion of sight impressions into thought images.” Experiments in material construction are juxtaposed with political and challenging content.

Panic Bodies was a treat in that it fused the numerous styles of experimental film into a millennial hybrid, weaving sharp observations with aesthetic wonder. Structurally, the film was separated into six vignettes, each preceded by a black and white etching of a Renaissance subject and a title, including Positiv, Passing On, Eternity, 1+1+1, Moucle’s Island and A Boy’s Life. Part personal narrative, part libidinal spectacle, and with an arsenal of visual pyrotechnics, Hoolboom’s film challenged the viewer to participate – to become embodied. The scourge of AIDS on the narrator’s body elicited personal recollections of the body in pain. This is a film about death, which means that sex is never far behind. The libidinal was explored both in a kaleidoscopic vision of penis play and the jouissance of vulva masturbation. Both scenarios were mesmerizing especially due to the jarring soundtrack that accompanied them.

I had hoped to encounter other troglodytes on my way to the cinema. None had emerged, and on my way back I had occasion to reflect on the nature of that day’s experimental film. Hoolboom’s Panic Bodies is a death poem in six acts, representing a body in pain and a body in life. Though the air was bitter when I left the theatre, the body that carried me home was alive in the cinematic afterglow.