The Festival Daily, September 12, 2002

It’s not a Festival without a Mike Hoolboom film, and this year the director returns with one of his best, the poignant and remarkable Tom, a portrait of his friend and fellow fringe filmmaker, 52-year-old Tom Chomont. Chomont is a notorious figure, a provocateur whose film and video work has upset the underground since the 1960s, and whose biography – an incestuous relationship with his brother, long involvement in the S/M scene, experiments with drugs and religion – would madden the mainstream. The two have been friends since the early 1980s, when Hoolboom programmed a night of Chomont’s work at Toronto’s Funnel film co-op.

Early in their friendship, Hoolboom experienced an uncanny – and decidedly metaphoric – sight. The two were sitting in Chomont’s tiny kitchen in New York late one night when Chomont “did something with his eyes,” and the room was suddenly flooded with a bright glare. “It was a white light that came from everywhere,” Hoolboom explains. “Every little detail in the room was sharp and illuminated. For Tom, the white light is the light you dissolve into when you die. It’s all pictures and all sound, all experience in a way. And it’s like cinema in a sense; if you projected every film ever made onto a screen, it would form this white light.

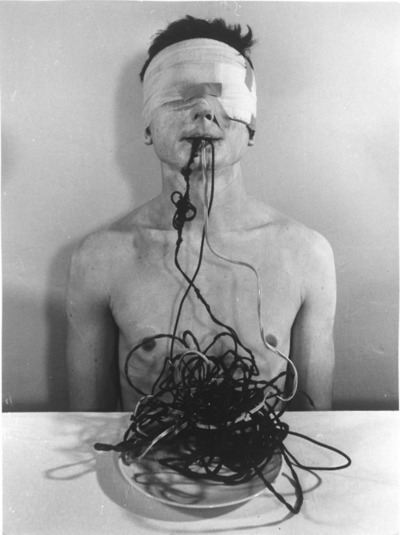

In assembling Tom, Hoolboom didn’t quite project every film every made, but he did borrow images from a great many of them. Chomont’s life is inextricably entwined with that of the cinema, and Tom is a complex skein built of images plundered from Hollywood blockbusters, obscure archival footage and his and Chomont’s own multifarious oeuvres. Interwoven through these are scenes from Chomont’s life (in fetish gear, getting his eyes checked, spooling film onto rewinds) mostly shot on glossy video.

Hoolboom was reluctant, however, to emphasize Chomont’s current struggles with both HIV and Parkinson’s. “I didn’t want to make this film about an emaciated, ‘gay white male’ dying of AIDS, looking like a victim,” Hoolboom says. “It needed to be about the Tom that I knew, filled with fantasy and imagination and stories. So one way to conjure that is with all these other stories. I wondered if the life of his unconscious might be more aptly conjured through the use of these other images.

Hoolboom spent about four years on the documentary, constantly travelling from Toronto to New York to film his friend. While Chomont was quite infirm – it would sometimes take him an hour to get his jeans on – he was delighted to participate in the project, having filmed himself and his friends for decades in films like Love Objects and Sadistic Self Portrait. “He was the perfect unexploitable subject,” Hoolboom laughs.

Tom also contains a parallel and impressionist history of New York, Tom’s lifelong home and the city Hoolboom calls the most photographed in the world. These images add a whole other richness to the film. “It’s a kind of metaphor for personality,” Hoolboom says. “Tom appears in so many incarnations and guises, and in that sense of metamorphosis, I also imagine the shifts of Manhattan itself, its convulsive eruptions.” The film is similarly mutable, a sublime record of a life lived, bravely, painfully, to the fullest.