Mike Hoolboom and the Second Generation of AIDS films in Canada by Thomas Waugh

Originally published in North of Everything, a book edited by William Beard and Jerry White. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2002

As I start to write this in October 2000, Canadians have been plunged into an election, but I’m more interested in the Minister of Immigration’s pre-election announcement of a new policy of compulsory HIV testing for all immigration candidates. The government responds to the warning of planetary crisis coming out of this year’s Durban International AIDS Conference 2000 by ineffectually trying to block it at the border and winning an election with the same stroke. It is as if, after two decades of the longest, mostly costly and fractious –and most unnecessary-epidemic in modern Canadian history, we have learned nothing. Instead of public outrage, we go on with our lives with resigned indifference to the flagrant act of bureaucratic scapegoating and brutality. For some reason, I think immediately of Mike Hoolboom, not only because he is a child of immigrants and an artist who has done his share of raging along the way (Kanada, 1993; Valentine’s Day, 1994). I think of him mostly because as an artist, infected like so many others with the retrovirus that is besieging bodies and continents, he is responsible within Canadian cinemas for unforgettable images of social otherness, corporal abjection, and psychic intensity that sum up the experience of the person living with AIDS as our societymoved through the 1990s. His images summon us not only to action against state cynicism, but also to conscience, lucidity, and affect vis-à-vis the medico-social crisis that we allowed to happen, and to a narrative identification with the corporal and existential meltdown – and illuminations – it entails.

In this chapter, I would like to focus on Hoolboom’s three principal short works of the 1990s that encompass this imagery. But first I must establish the context of other Canadian and video confrontations with AIDS over the last generation. On accepting the assignment to write a chapter about Hoolboom for this volume. I knew immediately that this prolific and versatile artist – the focus of a substantial critical literature that has enlisted many of Canada’s finest (and worst) film critics, curators, and fellow artists,1 not to mention a prolific film writer and curator in his own right – could never receive a comprehensive treatment in such a short space and that a narrow focus and selection would be necessary. AIDS certainly does not comprise the entirety of Hoolboom’s contribution as an artist, nor define him as a human being – far from it. But as he himself put it, after his 1988 diagnosis, HIV provided “a kind of unifying locus for my identity” and without a doubt his post-diagnosis work has transformed his mission and vision as a an artist.2 It has also found him a new and expanded audience, and elevated his “national” stature within this settler territory whose history we must not forget, was driven by overcrowded, unsanitary boatloads and planeloads of immigrants and refugees, and contoured by the propagation – both infectious and environmental, and eve3n military – of the scurvy, smallpox, cholera, typhus, typhoid, syphilis, tuberculosis, influenza, polio, and cancer that lay in wait for those immigrants and for the land’s unimmunized original inhabitants. It as if Plague Years, the title of Hoolboom’s collection of film writings, could serve equally as a history of Canada.

This assignment came right after I’d hosted Hoolboom at Concordia University and witnessed firsthand his extraordinary commitment and magnetism as a public intellectual/artist – a persona all too lacking in the public sphere of an English Canada mobilized around Stockwell Day, Mike Harris, and Paul Martin. I also observed the unusual power of his films, his voice, and his person to engage a non-specialist, interdisciplinary audience with no interest in experimental cinema. Hoolboom’s charisma, productivity and profile notwithstanding, I am a nonauteurist trapped in an auteurist volume: for Hoolboom’s work makes sense only, he might be the first to agree, as part of that larger cultural community and trajectory focused on and by the retrovirus in the last decades of the century. I would thus like to begin charting the first generation of Canadian AIDS audio-visual activism, the turbulent groundwater of other oeuvres and artists from which rose to the surface Hoolboom’s great AIDS triptych of the 1990s: Frank’s Cock (1993), Letters From Home (1996) and Postiv (1997).

Part 1

Because the number of the dead far outweigh the number of the living, we’ve divided the world into nationalities in order to mourn our dead more perfectly. And our mourning together, this must be the thing we call a country. Positiv

After its “discovery” in 1981, what is now called Human Immunodeficiency Virus and the devastation it caused were commonly perceived here in Canada as an “American” phenomenon, and a strictly “gay” one at that, but one mercifully lagging, epidemiologically speaking, several years behind the skyrocketing crisis in the States. Despite the futile alarms raised by The Body Politic and others, the virus soon infiltrated the bloodstreams but all too slowly the cultural consciousness of Canadians. In the US by mid-decade, a major counteroffensive of long and short films and video documentaries and even porno films about AIDS was in place, most from within the lesbian and gay “community;” the most visible mainstream cultural texts were the sanctimonious TV movie of the week An Early Frost and its spitting sister, Larry Kramer’s pioneering Broadway play The Normal Heart (both 1985). Canadian media artists, initially in Toronto, then elsewhere, inaugurated around 1984 an at first tentative trickle of cultural work about AIDS. The first Canadian documentary prophetically appeared in Toronto in 1985 (No Sad Songs, Nik Sheehan, co-produced by the AIDS Committee of Toronto, 26), a survey of gay community mobilisations intercut with dramatised fantasy vignettes, sewn together around a mournful portrait of a gay man with AIDS preparing for the end with campy humour and courage. AIDS media work picked up momentum immediately after Sheehan’s bold venture forth, most commonly community-based, but with arts networks also well represented, reaching its peak at the end of the decade.

The years since No Sad Songs, fifteen years or so of fevers and lulls in AIDS-related cultural production, can, alas, be divided into periods and genres. As I myself have recounted (1992), the popular melodrama genre, the “tearjerker”—and I do not use the term in any pejorative sense—was the first, most lasting and popularly effective of the cultural formats deployed in the international arena, unashamed in its aestheticisation of suffering, its narrativisation of loss, and its elegiac solicitation of mourning. The first cycle (An Early Frost; Buddies [Arthur Bressan, U.S.A, 1985]; Parting Glances [Bill Sherwood, USA, 1986]; and somewhat later Longtime Companion [Norman René, USA, 1990] and Together Alone [P.J. Castellaneta, USA, 1991]) bounced off its brilliantly cranky German mirror opposite A Virus Knows No Morals (Rosa von Praunheim,1986). The cycle moved to the mainstream, culminating in the international critical and box office hits of the early nineties Les Nuits fauves (Savage Nights, Cyril Collard, France, 1992) and Philadelphia (Jonathan Demme, USA, 1993), followed by a sputtering of indie latecomers, notably Jeffrey (Christopher Ashley, USA, 1995), and It’s My Party (Randal Kleiser, USA, 1996).

Canada’s two distinctive entries into the melodrama current, both musicals, came late: Laurie Lynd’s miniature narrative elegy, the crystalline RSVP (1991), and John Greyson’s rambunctiously hybrid agitprop feature, the comedy-romance Zero Patience (1993). Like many of the above works Zero was eloquent in its elegiac portrait of PWAs’ courage and rage, but was also close to von Praunheim in its spunky irreverence and beyond even him in its deployment of spectacle, eroticism, humour, and experimental effects adapted from art video… and puppet animation! Zero was also both an essay on the epistemology and politics of the epidemic and a cathartic melo engagement with two pairs of lovers challenged and ennobled by crisis and finally parted by death. A follow up Toronto feature by Cynthia Roberts, The Last Supper (1994), an impressively controlled adaptation of a PWA theatre piece by Hillar Liijot about the dancer protagonist Chris’s ritualised assisted suicide, featured a real-life actor Ken McDougall performing his own final struggle as it turned out. Shot in real time at Casey House, the Toronto hospice, The Last Supper garnered positive notices and the Teddy Award at Berlin yet immediately disappeared off the radar screen of Canadian canon formation—it is unfortunately not even available on video. The Vancouver video feature The Time Being, by Kenneth Sherman (1997), was also noteworthy for its achievement and innovative in its narrativisation of a gay couple’s encounter with sickness, death, and mourning. Neither Roberts’s nor Sherman’s films succeeded in having an impact beyond their festival launches and the tearjerker momentum might have seemed spent.

Yet somehow it carried on, and led to two major English Canadian feature films at the start of the new decade, The Perfect Son (Leonard Farlinger, 2000) and The Event (Thom Fitzgerald, 2003), both assisted suicide narratives (why do they appear in three-year intervals?). Both of these latter two films were greeted with critical respect and boxoffice indifference alongside cautious rumblings from within the queer press and elsewhere: was there perhaps just a smidgen of anachronism about fully wrought AIDS suicide melodramas set within privileged North American white gay male milieus in the rapidly evolving global context, shaped by new treatment realities and the geopolitical landscape of pharmaceutical blackmail? As we shall see with the work of Greyson, Fung and Hoolboom, melodramatic desire settled much more fruitfully somehow and intervened more concretely in the “marginal” works of the avant-garde indie scene than with Telefilm Canada (with one “movie musical” exception…).

But melodrama was only one of the genres favoured in the wave of artistic productivity around AIDS in the late eighties and early nineties, and Zero was not Greyson’s first contribution to it. “AIDS is a war,” this indefatigable anti-censorship activist and wunderkind of the Toronto video and film scene had announced in 1990, summarising the political urgency of so much AIDS media activism, “there’s no time for artsy debates about formal issues.” He then went on to paraphrase the contrary view that “AIDS is a war, not just of medicine and politics but of representations–we must reject dominant media discourses and forms in favour of a radical new vocabulary that deconstructs their agendas and reconstructs ours” (1990).1 In fact, his own prolific video work was an energetic embrace and negotiation of both positions simultaneously. Greyson must also be seen as a facilitator, critic and impresario, working infectiously behind the scenes of the first wave of Canadian film and video work. In the same article, he listed the genres of AIDS media activism, and contributed to virtually all of them either through directing or offscreen support: cable access; documents of performances; memorial documentary portraits; experimental deconstructions of mass media; educational tapes on prevention and other urgent topics for specific audience targets; documentaries about AIDS Service Organizations; safer sex tapes; activist documents of demonstrations, etc.; and PWA-directed tapes on such issues as alternate treatments. The Toronto video cable project which Greyson organized with PWA video artist Michael Balser encompassed most of these genres and enfranchised a whole diverse lineup of young artists and community voices before being shut down by Rogers Cable’s kneejerk censorship in early 1991. It could be argued that a no less palpable contribution by Greyson around the time of Montreal’s V International AIDS Conference in 1989 was strictly curatorial. Affirming that the wave of in-the-streets, in-your-face community activist video originating mostly in New York, was on a par artistically with the more culturally prestigious and visible utterances–and in fact he didn’t care whether it was or not, as we saw in his epigraph–he compiled and circulated a cornucopia of tapes for cultural, educational and community work. His package, Video Against AIDS, co-curated with American Bill Horrigan in 1990, contained seventeen American, two British and three Canadian videotapes (Greyson’s own The ADS Epidemic, to which I shall return; Michael Balser and Andy Fabo’s allegorical Survival of the Delirious [1988]; and “Youth Against Monsterz”’s Another Man [1988, 3], a Toronto collective effort aimed at high school students, part media rebuttal and part safe sex clip). The overall package ran the gamut from obscure art video to encyclopaedic grass roots assemblages of raw documentation and dramatised community agitprop, enshrining alternative media as the place where the action was. VAA literally changed the face of AIDS in North American arts landscapes.2

The autobiographical status of Les nuits fauves was unique for a feature-length work of cinematic fiction but echoed a crucial genre in both PWA literature (Hervé Guibert, Paul Monette, Michael Lynch, Ian Stephens) and fine art (David Wojnarowicz, Robert Mapplethorpe, General Idea). Yet Collard’s stupendous and indulgent film had been surpassed in its epochal raw intensity by another first-person posthumous work that appeared the same year, the small format video documentary Silverlake Life: The View From Here (Tom Joslin with Peter Friedman, USA,1992). The following year saw both Derek Jarman’s Blue (UK) and Gregg Bordowitz’s Fast Trip, Long Drop (USA), two very different self-referential works, film and video, ascetic and carnivalesque, testamentary and “the-world’s-my-oyster” respectively, works that cemented the emerging autobiographical cycle of independent non-narrative film and video as the most significant of the 1990s. (Certainly the activist wave of the late eighties had had autobiographical tendencies, but this wave submerged in its collectivist ethic most individualist discourses of makers’ lives as creative raw material.)

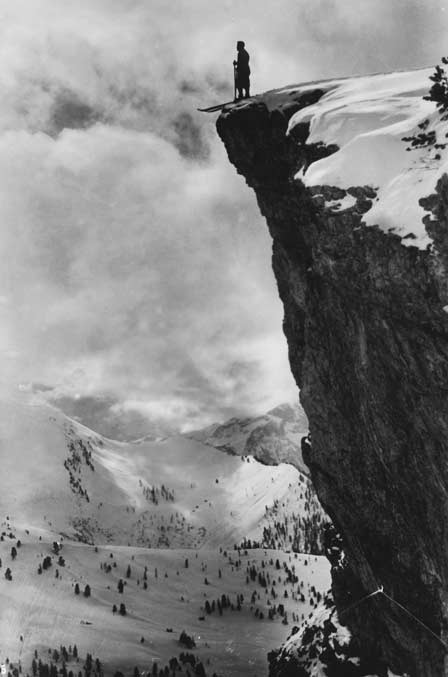

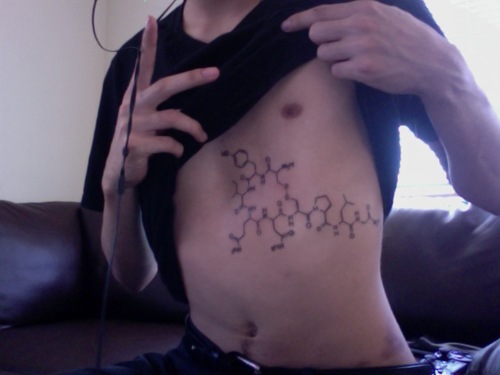

Canada’s distinctive representation within this international convergence of autobiographical work around the beginning of the nineties had in fact preceded the above autobiographies and was manifold. In addition to short experimental video pieces by Balser and Fabo in Toronto, and Zachery Longboy in Vancouver,3 there were two principal longer works. The tender and lyrical video essay Récit d’A by Esther Valiquette (1990), an apparently conventional PWA portrait discreetly layered over the artist’s own “coming out” as infected, and over her reflection on the body, mortality and landscape, announced a new voice and a new departure beyond the demographics of Canadian AIDS artwork in the 1980s (male, gay and anglophone).4 According to Chantal Nadeau (1997, 32-6), Valiquette’s work was “an intense, powerful voice telling of the difficulty of seeing oneself as a ‘positive’ body… making a representation of the virus merge with a representation of her body, appropriating the aesthetic of science as a code of self-representation.” Another Canadian contribution to the genre was from the West Coast: Dr. Peter Jepson-Young, a gay doctor with one of the pioneering Vancouver AIDS practices who was himself diagnosed in 1986, began producing weekly broadcasts for the Vancouver CBC station in 1990, and a lively and inspiring series of 111 short vignettes appeared before his death in 1992. Repackaged that same year for the CBC by David Paperny as The Broadcast Tapes of Dr. Peter, this cumulative work preserved the broadcasts’ diary format, and showed among other things, the undaunted hero, literally blinded like Jarman by an opportunistic cytomegalovirus infection, veering cheerfully down a BC ski slope. Tapes was less about the then cutting-edge video activism and analysis than about giving the “general public” a brave and dignified face for the syndrome. Its Academy Award nomination and US broadcast on HBO reflected this mainstream viability. Otherwise, neither Récit nor Tapes registered within the international AIDS cultural vanguard, and not only for the usual factor of their “Canadianness.” Valiquette’s beautiful work had the disadvantage of being in French and English at once and almost inaccessible in either language versions, as well as feeling a bit literary for anglo tastes and both dated in its political innocence and ahead of its time in its confrontation with the metaphysics and iconographies of corporeal mutability; Jepson-Young’s work, which went on to a book version by Daniel Gawthrop (1994), went by virtually unnoticed by the movement’s New York and London-centred gatekeepers, Douglas Crimp, Paula Treichler, Cindy Patton, and Simon Watney,5 perhaps because of its mainstream marketing or else because the image of a privileged white gay man dying of AIDS, an Anglican to boot, seemed no longer “front line.”

Part II

We didn’t know back then. Nobody did. Frank’s Cock

Hoolboom’s 1988 diagnosis took place in the same Vancouver hospital where Dr. Peter’s practice and final years were lived out, St. Paul’s. Known then as a twenty-something Toronto experimental filmmaker, with a reputation for formal rigour, celluloid purism in the age of video, and film community activism, Hoolboom’s work fluctuated between structural minimalism and excess. Having discovered the writer within, he was increasingly pushing the “new talkie” tendency of eighties avant-gardism to its limit, developing clear talents as raconteur, diarist and aphorist. An ardent collaborator, then as now, Hoolboom moved to Vancouver at the end of the decade to nurture his working and personal relationship with Ann Marie Fleming, an emerging figure in that city’s experimental scene. Hoolboom’s seroconversion, that critical moment of truth later rehearsed repeatedly in his 1990s films, not only altered his life but also re-situated him as an artist in the international and Canadian context I have just sketched:

So one Saturday afternoon we trooped off together to have our juice drained [at a Red Cross blood drive] and that was that. Until a letter came for me in the mail. Saying there was a problem with my donation. My blood. That I should go see my doctor. That’s when he told me I was HIV positive. He was a young guy who worked in the clinic and he handed me a bunch of pamphlets and said, “I don’t really know anything about this disease, I’ve never talked to anyone who’s had it before but read this.” I didn’t handle the news all that well. I kept it to myself and waited to die. Drank a lot. Phoned up a bunch of people I’d slept with and passed the word along. And began a frantic tear of short films that’s lasted till now. Never wanting to make anything bigger than my head because I didn’t figure I’d be around to finish it. I just didn’t know (de Bruyn 1993, 5).

The first generation of AIDS artists, from Bressan and Valiquette to Vito Russo as well as the writers and visual artists I have mentioned above, had passed or were passing the torch, almost all dead by the time of this interview, given just after shooting Frank’s Cock. With this film, Hoolboom found himself for better or worse among a second generation of figureheads of the AIDS arts movement, one of its first male artists not to have emerged from gay cultures and communities. Though the era of in-the-streets activism seemed to be passing—at least in North America—many of the other artistic concerns I have inventoried would be taken up and reinvented in Hoolboom’s AIDS triptych: the melodramatic impulse; the recycling and reconstruction of received media images; the metaphysical thrust; the negotiation between agitprop urgency and formal innovation; and the exploration, transgression and affirmation of sexuality.

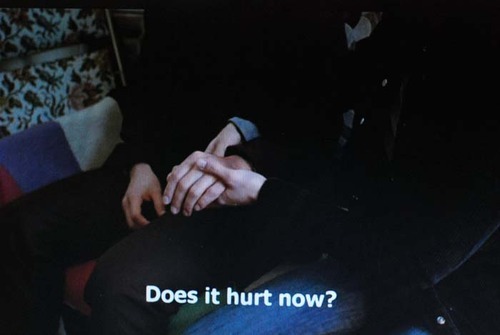

Vancouver had also been where Hoolboom encountered Joey, a fellow member of a PWA group, whose story would become dramatised as Frank’s Cock, the first panel in Hoolboom’s AIDS triptych. Despite its risqué title, its marketing as experimental, and its consumer warning of “extremely explicit,” Frank’s Cock is basically a populist melodrama, a narration of a gay romance and its impending end in Frank’s imminent death, notable for its power of affect and identification. The narrator, played by then unknown Western Canadian actor Callum Keith Renney, tells of his first encounter with his lover Frank, and their mentor-novitiate relationship of ten years, a love story embellished by feats of raconteur braggadocio. The eponymous appendage—described but unfortunately not seen—signals Hoolboom’s appropriation and celebration of same-sex desire that had been at the core of the queer arts counteroffensive for almost a decade, but was relatively new within Hoolboom’s hitherto flamingly heterosexual sensibility.11 Hoolboom’s visually and narratively intricate format was based on a direct-address onscreen narrator and a four-way split-screen mosaic structure and struck an immediate chord. The unnamed Renney character occupies the upper right quadrant, frontally addressing the camera in informal, voluble, confidential closeup. After the upper left awakens with a montage of physiological microphotography (no doubt connoting the invading micro-organisms, or all the swimming cells that Hoolboom repeatedly tells us in film after film die every day in the body), the lower left quadrant recycles Madonna’s banned Erotica video, and eventually the lower right chimes in with closeup excerpts of anal and oral coupling from commercial gay pornography. All three peripheral quadrants are more or less synchronised with the ebb and flow of Renney’s tale, and are visualised complementarily with Hoolboom’s characteristic tinted black and white. The soundtrack includes his unabashed appropriation of romantic if not outright sentimental music, including that of another Frank, Mr. Sinatra. Conciseness is perhaps the key to the film’s impact: one hardly believes that such layered narrative complexity, visual virtuosity and emotional wallop have all been demonstrated in only eight minutes. Hoolboom would return to variations of this tight polyphonic formula for his subsequent two films.

If Hoolboom’s breakthrough, rewarded with festival prizes and wide circulation, had come out of an interpersonal encounter and a discovery of other sexualities, the next film was more about a retroactive Mike-come-lately discovery of the political movement that had grown up within the epidemic in the 1980s. A visit to an ACT UP rally in New York12 had occasioned yet another transformation in Hoolboom, by his account, from a living room observer of the AIDS crisis to a participant in a collective belonging:

…we realized that most of us–and there were thousands–were positive… a congregation of those who had laid their beloveds into the ground, and come here still daring to hope… Vito Russo was the last to speak, and I’d never heard 20,000 people cry at the same time–leather giants and drag queens holding each other in the flood. Something that day changed for me… (1998, 112).

Hoolboom subsequently discovered a speech that Russo had made in Albany in the summer of 1988, the text of which became the core of Letters from Home (1996). The elements of direct address, narrative excess and melodramatic affect have been extended from Frank, but this time the multi-layered polyvocality is sequential rather than simultaneous, and the unitary dramatized narrative premise is lifted. The narrative now migrates from voice to voice in a multi-racial, multi-accented, multi-generational procession of protagonists and narrators, onscreen and off (mostly figures from the Toronto arts scene, where Hoolboom had by this time re-established himself). Frank’s individual-focused simplicity was set aside and the film now aspires in its allegorical casting beyond gay community to the collective universality Hoolboom experienced that day with ACT UP. Russo’s text is a narrative of his and his friends’ experiences as PWAs, and an accusatory indictment of the avoidance, indifference and stigmatization of state (ACT UP’s usual target) and society. Hoolboom fleshes out the speech with his own characteristic dream narratives of a diagnosis (borrowed from Herman Hesse) plus a bodily revelation, a personal anecdote, some Canadian content, and even more high contrast visual flair than before. Most importantly, the rotating first person voice includes, for the first time in this series, Hoolboom himself, briefly superimposed over water images and sounds, appropriating Russo’s words “As a person with AIDS” for himself. The procession finally culminates with Renney, this time recounting first-person a sickbed encounter between the PWA character he plays and a friend, incorporating the melodramatic tropes of flowers, embrace and epiphany sealed in a mutual looking into eyes. All of this unfolds beneath the most manipulative rendition of “Amazing Grace” imaginable, frail piano transposing into organ swelling polyphonically under a glorious sunrise that blazes out Renney’s face. The effect of this anthem is as devastating as it is absolutely true, having migrated from the 19th century abolitionist movement to the 20th century anti-addiction movement and most recently to both AIDS culture and Oprah-land. But that’s not all: the final shot catches Hoolboom, in extreme closeup, looking into the lens—a shot that retroactively takes over the film qualitatively.

The introduction of the new multiple therapies around the time of a later Canadian conference, the Vancouver International AIDS Conference in 1996, had spelled a paradigm shift of AIDS discourse as well as a turning point in the work of all three of the artists I am considering. The shift entailed among other things what Paula Treichler (1999, 325) has called a “transition from a concept of AIDS as a classic epidemic of acute infectious disease to that of AIDS as a chronic, potentially manageable disease” (at least in the privileged and medicared pockets of the so-called developed world). This miraculous return–at least for now–of many of the sick to the ranks of the working populace—including Hoolboom, Andrews and McCaskell—and of the arts critic from the job of necrologising dead artists to the luxury of monitoring continuing oeuvres and maturing artists, occasioned a parallel shift in the symbolics and genres of AIDS texts. Destroying Angel (1998, 32), a short film by Hoolboom’s old Sheridan College colleague, Philip Hoffman, co-directing with American PWA Wayne Salazar, would in some ways epitomise this shift. Pursuing familiar diaristic and autobiographical conventions by expanding the frame into both co-authors’ “families,” the film’s narrative and real-world dénouements confound the AIDS mortality cliché and viewers’ expectations: the PWA turns out to be a survivor mourning Hoffmann’s partner, Marion MacMahon, the third artist in the diaristic triangle, fallen to cancer. By 2000, the AIDS melodrama was for all intents and purposes obsolete such that one critic, José Arroyo, could welcome the pill-popping French feature film Drôle de Félix, what he calls an “AIDS romance,” in the following terms (2001): “to my knowledge at least, one of the first films with an HIV+ protagonist who is offered the expectation of a future, however delimited. In this charming romantic tale . . . the final clinch between the lovers isn’t a deathbed scene but the beginning of an idyllic holiday.”

Hoolboom’s third AIDS panel Positiv had in fact offered the expectation of a future three years earlier, going into circulation both separately and as part of the six-film package Panic Bodies. With its serene image of acceptance, bliss (both carnal and spiritual) and eternity, and its presiding collaborator Tom Chomont, Bodies seemed to answer back Hoolboom’s previous long work, the scandalous House of Pain (whose resident collaborator had been the Toronto performance artists of extreme sensation Paul Couillard and Ed Johnson). This latter film, a nightmare inferno of visual intensity, erotic extremes and corporal abjection, part Dantesque, part Rabelaisian, had been released after Frank’s Cock in 1994-95, put together out of four semi-autonomous shorts. It was as if Panic Bodies’ riposte to House of Pain symbolically articulated the 1996 shift. Appearing as it did in 1997, Positiv would of course not have had the full retroactive distance to assess this paradigm shift in such explicit terms, but the film does articulate an important evolution in Hoolboom’s AIDS conception all the same, as if demonstrating and updating Russo’s original ultimatum that AIDS is about living.

Because we already know how we’re going to die. What we don’t know, what we’re asking you now, is how we’re going to live… AIDS is a test of who we are as a people…

Hoolboom’s self-reflexive insertion into the text is now fully realised, no longer vicariously embodying “Joey” (Frank’s real-life lover), Callum Renney or Vito Russo, but maintaining a continuous presence on the screen, his own face, his own body, his own biographical trajectory, his own personal circle of family and friends. Positiv returns to Frank’s four-panel split screen structure, and not only does he fully take over Renney’s place as the frontal onscreen narrator in the upper right, but “performs” in the other quadrants as well. He recycles self-reflexive narrative fragments from earlier apparently uncompleted projects that evoke his memories of growing up and moving away (one fragment where he is decked out in angel wings on a lonely highway) as well as his more recent experience of medical tests and treatment (Hoolboom engaged in the prophylactic inhalation of aerosol pentamidine to ward off pneumocystis pneumonia, shots that curiously extend the orality of the earlier panels). Of this experience of medicalisation, the narrator pronounces,

There’s not much the doctors can do for you, except draw (your) blood out for tests. In fact the more your condition worsens the more tests (they seem to need.) are demanded, as they seek ever finer ways to monitor your decline. Your identity is clinging to these numbers, your viral loads, the ratios of enzymes and tissues that continue to betray you. [The passage scored out appears in the Plague Years version of the script only, while the parenthetical clause is in the final film version.]

At the same time the “found footage” strands veer in their relation to the voice from exact synchrony (shots of detached hands matching the narrator’s memories of his childhood piano efforts and conceptions of his unintegrated body parts) to delirious arbitrariness. The consistent thread through all the found footage, from sci fi and pedagogical films alike is corporeality, gleanings from pop culture’s neurotic obsession with bodily transformations, from Ken Russell’s Altered States to Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers’s Shall We Dance. Least successful of the three works in terms of mainstream festival audience impact and prizes (at least as an autonomous short film), Positiv is in many ways the most challenging and original of the three, departing from the land of melodrama and finality into its own distinctive personal territorial flux, where “I guess I’m gonna have to wait it out”—part holding pattern, part stock taking, part manifesto.

Part III

…just all of a sudden it comes to you–a new word has taken the place of your body. … the little sticker on your chest doesn’t say, “Hi I’m Mike,” it only says “AIDS” because you don’t belong to yourself any longer, and as you get older it’s not you they’re talking to anymore it’s the sickness…13

In the final part of this chapter I would like to revisit Mike Hoolboom’s AIDS triptych as a whole, and focus on his performative articulations of the sexualised, infected, abject body, in short, the queered body. In the 1980s I had associated Hoolboom with a masculinist wing of Toronto experimental cinema, a certain Sheridan College-Bruce Elder cohort, approximating the network that Hoolboom himself had once termed the “escarpment” school. (1991, 43). Within the discipline of film studies, a tempest in a teapot called “The Cinema We Need”14 had gripped the mid 80s and summed up for me many of the aspirations of this cohort. The polemics had endowed a particular cultural aesthetic with imperial cultural and political pretensions on a national scale, without any serious ramifications for the rest of the cultural struggles going on elsewhere within these national borders. It was a dialogue des sourds by straight white anglo male intellectuals living in Toronto (and Ottawa) and pushing a kind of intellectualized modernist experimentalism as the solution to the [English-] Canadian cinematic impasse. Of course the cohort’s unquestioned masculinism was only part of the problem, but for me it was the start and end of the debate. However, Hoolboom later affectionately credited the cinematography of Letters from Home to his longtime collaborator Steve Sanguedolce, the “cream of the eyejocks,” (with whom he had also made the pre-diagnosis road movie Mexico, in many ways Hoolboom’s most masculinist movie15). In so doing he accidentally touched my queer Montrealer’s nerve that had blocked me out of the Toronto jock avant-gardism of the previous decade. The Hoolboom of Letters had long since moved beyond this jockdom, despite the vestigial traces of athletic metaphors in the AIDS films, e.g. “Joey” wanting to be “Wayne Gretzky with a hardon” in Frank, his fascination with the size of the titular cock and Hoolboom’s receptivity to ACT UP militarist and firefighting rhetoric in Letters From Home. Even at the time of his diagnosis in the late eighties, Hoolboom had already been moving beyond the eyejock visual primacy and intellectualism of his earliest work. He was entering the territory of sexual iconoclasm with his heterosexual diary and performance films, where his female partners of the day were offering the camera their bodies, sexual engagements or relationships with the filmmaker—as well as artistic input.16 In this territory of the body, the cracks in the machismo, its vulnerability, volatility and relativity, seemed to be spreading.

I do not mean to overwhelm Hoolboom’s frenzied productivity of the first post-diagnosis years with a teleological trajectory, all the more so since many of the short films that came out one after another had been based, like Mexico, on material shot earlier. Still, what is clear is that the 1993 Hoolboom of Frank’s Cock was a vastly different species. The transformative effect of his diagnosis was repeatedly being confirmed in interviews:

Our identity hinges on our body. Now what happens to that image once you become HIV positive?… I worked harder. Finished more films. And quite unconsciously began a series of films that take the body as its subject… (de Bruyn 1993, 6).

It does not require a simplistic biographical reading to recognise throughout the triptych the obsessive repetition of this diagnosis moment. I think of the charged use of Billy Holliday’s “You’ve Changed” on the soundtrack of Letters or of the opening dream narrative of Letters from Home, punctuated by ominous flash closeup shots of a man in a surgical mask:

… as I get closer I can see a man stooped over a small set of crystals gathered on a table. He doesn’t look up as I get close and I understand each of these crystals represent a part of myself…He looks up then and for the first time I can see he’s wearing a doctor’s surgical mask. He says, ‘I’m sorry. I’m afraid you’re HIV positive,’ pointing down at the pile, and sure enough, right in the middle of the glow, there’s an off-colour stone slowly wearing down everything around it. I guess the future’s not what it used to be.

This whole sequence is topped off by found footage of conflagration and catastrophe. The spectator also repeatedly experiences variations of this trans-/per-formative pronouncement that are more social than medical, the enactment of stigma through speech or, even more profoundly, through the look. Reflected in the haunting look back at the lens of the speakers in Letters and of Hoolboom himself in Positiv, and in the proliferating eyes in all four quadrants as Positiv moves towards its end, this stigma is repeatedly recapitulated by the voice: If I’m dying from anything, it’s from the way you look when I see you with that funny kind of half smile on your face… (Letters) …you read the whole cruel truth on their faces. You watch yourself dying there… (Positiv) At the same time, indissociably, there are the moments of knowing constituted by “coming out” tropes, those Foucauldian exercises in reversing and reclaiming stigmatising discourses, once the sacrament of gay liberation, now the political ritual of the constituency of the infected. As in Bordowitz’s Fast Trip four years earlier, Hoolboom repeatedly performs onscreen his identity, through the continuous confession, or rather affirmation, of seropositivity and illness. Taken together the three narrations of his triptych include about a dozen such affirmations, either enacted or narrated.

Hoolboom’s performance of identity through transgressive sexuality is even more obsessive, not only spoken but also visual. This is the zone where even Cronenberg fears to tread, the zone beyond Greyson’s flopping penises and anal puppets of Zero, the “extremely explicit” zone of throbbing indexical flesh. From the porno display and the romantic anecdote that creates worship of rimming in Frank, to the intensely ecstatic sequence of kissing and lovemaking by nude male couples under the shower in Letters, to the variously farcical and transcendent masturbatory frenzy of A Boy’s Life and Moucle’s Island, the two lusty chapters which seemingly counterbalanced the comparatively chaste serenity of Positiv in the composite feature Panic Bodies. In this latter work, Hoolboom, the narrative and autobiographical subject with intense eyes, earnest voice and blistered flank joins a processional fresco of a dozen of so other panic bodies through its six episodes. Cumulatively, the filmmaker create equivalences between the affective intensities of mortality with the sensory frenzies of genitality, and thus questions even further the ambiguous boundaries between sex and death. Throughout, it is this obsessive play with knowledge and revelation – verbal, visual, corporal – that Eve Sedgwick identifies as having been “inexhaustibly productive of modern Western culture and history at large,” “a frightening thunder (which) can also, however, be the sound of manna following.”

The erotic performances in Panic Bodies panicked more than one lazy film critic. Commenting on Bodies’s being awarded the best Canadian feature award at Montreal’s 1999 Festival du nouveau cinéma et des nouveaux médias, Le devoir’s Odile Tremblay did not hesitate to collapse sexual gesture into literal embodiments of authorial identity and personality, showing into being: “How the devil could this confused film have seduced a jury, endlessly pushing its experimental side towards the land of the marginal? Excessively ambitious, this narcissistic documentary woven out of homosexual obsessions (we are forced to watch countless masturbation scenes) seems to want to demonstrate for the sake of demonstrating, upset for the sake of upsetting, provoke for the sake of provoking, without delivering any coherent message at the end of the road.” (9 Feb. 2000, B10).

Out of the mouths of homophobic incompetents comes something approaching an understanding of the artistic effect of Hoolboom’s performative, autobiographical marshalling of sexual imagery. The performances of two discrete identities, sexual and sero-, whether verbal or gestural, are relayed separately or in tandem. Hoolboom produces or archives, looks at, shoots, shows and speaks both the gestural repertory of sexual marginality and the bodily performance of immuno-marginality. But the two identities tend to merge in their instability, all the more so within the formats of split screen, sound-image counterpoint and narrative identification, as if together they constitute an expanded and fluid identity configuration. Beyond the post-Stonewall notion of fixed sexual essence, this is a sphere of abject stigma and otherness, in short, of queerness. Each of the three films is structured by these performative moments, where voice confronts body and sexual act, image confronts image, speech and sound confront images, and all together enact identity. Positiv, the final panel of the AIDS triptych, the most fully realised consummation of Hoolboom’s autobiographical discourse, is the ultimate stage in his confrontation with both his body and his identities. It seems the perfect demonstration of what Annamarie Jagose has called “the multi-directional pressures which the AIDS epidemic places on categories of identification, power and knowledge… a radical revision of contemporary lesbian and gay politics… a radical rethinking of the cultural psychic constitution of subjectivity itself” (1996, 94-5). The social subject known as Mike Hoolboom may or may not be bisexual,17 but Mike Hoolboom the filmmaker is here and queer.

Interestingly, Hoolboom has connected the articulations of identity, both as sexual outside and as infected, to a general shift towards narrativity in these three works and elsewhere:

…many of those traditionally excluded from even marginal modes of expression – women, people of colour, gays – have an abiding interest in a narrative practice because their experience must be accounted for, their stories so long ignored given shape by communities of interest… I guess I’ve rediscovered stories over the last few years as I’ve had to come to grips with my HIV status, my own imminent decline.. The time I’ve got. I have to make resolutions quicker, to go back and try to make explicit the patterns of dissent that have narrated my own confusions. This looking back is undertaken with the hot breath of The End on my back, and occasions my own need to tell stories again. To recount what happened and why.

This movement toward narrative accompanied his general disillusionment with the avant-garde through the 1990s, a contradictory development that saw him publishing Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, a collection of interviews with his fellow practitioners of independent and avant-garde film/video in Canada, while at the same time pronouncing the eulogy for eyejock avant-gardism.

“The work I make and the work of others I’m interested in is very small work – not in ideas or commitment – but in terms of an economy of exchange. It lives outside the traditional menus of attention, of theatre chains and daily papers, and this marginal perspective allows it a freedom it couldn’t have elsewhere. The danger in this freedom is solipsism, that “avant-garde” film becomes another genre like the western or the horror film. But without a social context. So it begins to implode. To restage its own history with a visual rhetoric that is increasingly difficult to follow by any but the most versed of its devotees… As I’m nearing (the close of this book Fringe Film in Canada) it’s begun to take the shape of mourning, of a lament for a practice whose days are clearly numbered… Because a real artist, someone who isn’t just making work out of a recipe book, is trying to figure how to live…”

The growing disenchantment with the avant-garde was mutual, if the fiercely hostile, sarcastic and ad hominem review of Letters from Home by Bart Testa is any indication. Testa taxed the “Hoolboom franchise” with a wide range of shortcomings: “coping (sic) techniques from experimentalists such as Bruce Elder and Bruce Connor, playing “dial-a-stylistic”, “rotating personae,” “the duplicity of special pleasing that also uses the pleas of human universalism,” and in general producing “moralizing,” “wordy,” “arch”, and ephemeral work, as well as “AIDS rhetoric” that dates badly. Even the praise is faint and begrudging: Letters is a “strong renter,” “barely sidestep(ing) AIDS clichés, and Hoolboom is a better “magpie montagist” than Bonnie Klein! Hoolboom’s shortcomings are, of course, crimes against an (imagined) avant-garde of an earlier era with its doctrinaire culture and ethics of formal innovation and artistic coherence its politics of entrenches social marginality, and its phobic fear of both sentiment and commerce. Both these crimes were arguably virtues, all of them, in the postmodern 90s of multiple and crossover audiences, identities and practices, hybrid forms and influences, and queerly volatile political and cultural configurations of mainstreams and margins.

Hoolboom’s affirmation of narrative as part of a new aesthetic hybridity, his embrace of autobiography and documentary, performance and eroticism, melodrama and activism, his growing detachment from the avant-garde, enabled the discovery of new audiences and constituencies. The darling of both experimental and mainstream festival audiences as well as the AIDS community and education organizations, Hoolboom was embraced, even appropriated, perhaps most enthusiastically by lesbian and gay audiences anchored in the worldwide networks of lesbian/gay/queer film and video festivals. For the copywriters at Montreal’s Image et Nation festival, who offered Hoolboom a retrospective in 1998 and an update program in 2000, the Toronto filmmaker has “a unique vision of living as a gay man with AIDS… a revolutionary subject… Described by some as the most important Canadian filmmaker of his generation, this adventurous and challenging experience will change the way you look at film forever.”

As I finish writing this during the surprisingly fierce Christmas of 2000, the election, long since over, has maintained the status quo, the policy of scapegoating silently takes it source, and Canada has increasingly become Kanada (with There’s No Business Like Show Business, now enshrined as the national anthem). The South African and Barcelona AIDS conferences of 2000 and 2002 made the Vancouver Conference’s momentary space for paradigm shifts and hope seem a distant memory, as the dimensions of the global castastrophe—and the soaring infection rates in Canadian back yards—become increasingly clear. Showing Positiv in recent years to various groups, I found that audiences and I don’t cry as we did for Frank’s Cock and Letters from Home. Instead, dry-eyed but no less profoundly moved on other levels, we engaged with Hoolboom’s serene acceptance of the organic otherness of his body, his movement beyond the concrete particularity of seropositivity, sickness and sexual identities, towards a generalised queerness that he performs together with his perplexed sickbed visitors and film spectators alike. Meanwhile, Hoolboom’s newly deepened commitment is to writing. A novel is in progress, whose title will include some variation of the past tense of the verb “to say,” the AIDS anagram he has been playing with throughout the 1990s, fascinated by how the migration of a single letter in a devastating acronym becomes the compulsion to speak, create, perform. Whether the writing extends, diverts, or problematizes Hoolboom’s relationship of shared engagement with audiences and impels his continued artistic effort to “figure how to live” will depend on the changing social context as this second generation of AIDS artists, of which he is a part, plays out its mission, ceding, in turn, inevitably to a third generation of AIDS artists. As Hoolboom said in 1993, “It used to be that we thought meaning was contained in the work, but now we understand that the work is part of a social relation that is always changing. Always alive.”

1. AIDS-related video works directed by Greyson in those prolific years of the late eighties include Moscow Doesn’t Believe in Queers (1986), The Ads Epidemic (1987), Four Safer Sex Shorts (1987), Angry Initiatives, Defiant Strategies (1988), The Pink Pimpernel (1989), The World is Sick (Sic) (1989). See Folland 1995 for a useful contextualisation of this early Toronto AIDS video activity within international theory and practice.

2. Chicago’s Video Data Bank and Toronto’s VTape sold up to 200 copies of the 3-cassette package to arts and educational institutions, but its impact was even wider than the sales suggest since it was often handed over free to community organisations. Data kindly provided by the two organisations, December 2000.

3. Respectively, Survival of the Delirious, 1988 and Choose Your Plague, 1993.

4. The lag in Quebec artistic responses to the Epidemic is curious. Denys Arcand and his cast put together in 1985 the first mainstream Quebec cinematic portrait of a PWA in Déclin de l’empire américain (released in 1986): the “tragically” gay sex-addict art historian who pisses blood and thereby absolves/exculpates the promiscuity of his heterosexual friends. This erroneous and pernicious image figment would later be justified by the actor Yves Jacques after his own coming out a decade later by claiming that little had been known at that time of AIDS–the same year that universal HIV screening was introduced into the blood donation system in the “industrialised” worlds, Montreal AIDS community organisations were already underway, and Rock Hudson’s diagnosis and death became the number one media story! My hypothesis is that the resignation of the post-referendum arts scene, articulated in an apolitical formalism, did not spare Déclin, and coupled with cultural insulation from the North American media’s AIDS crisis of conscience, allowed Quebec artists and writers to slumber on in the city with the highest infection rate in Canada until the V International Conference on HIV/AIDS in Montreal in 1989. The first Quebec French-language audio-visual work of any substance, Récit d’A appeared the following year: a personal masterpiece by a seropositive heterosexual woman making her first tape who nonetheless somehow felt compelled to journey to San Francisco to interview a person with AIDS…. When in 2003 Montreal gay journalist Matthew Hays developed a piece for The Toronto Star on the Jacques PWA character’s amazing resilience in Arcand’s sequel to Déclin seventeen years later, Les invasions barbares, Arcand hotly denied that the original character had anything to do with AIDS, contradicting an interview he’d done with same critic a decade earlier. The article was effectively killed but salvaged by Take One (Hays 2004).

5. Tapes is also ignored by Catherine Saalfield, the compiler of the videography in Juhasz 1995, as well as by Juhasz herself, a surprising omission in the light of the book’s aspirations to definitive historiography. However, a paragraph’s attention was accorded in Baker 1994, 84-85.

11. Exceptionally, Hoolboom plays with drag in Man (1991) and The New Man (1992), co-directed with the feminist Fleming.

12. In the company of Tom Chomont, the gay PWA experimental filmmaker from New York, a key collaborator of the 90s, whose letter about a near death experience would become the basis of Eternity, part of Hoolboom’s Panic Bodies in 1998, and who would be the subject of Hoolboom’s portrait Tom (2000).

13. This excerpt appears in the Plague Years (1998) version of the script, p. 159, but not in the final film.

14. The principal texts in the “The Cinema We Need” debate (authored by Bruce Elder, Bart Testa, Piers Handling, Peter Harcourt, Michael Dorland, and Geoff Pevere and published in The Canadian Forum and Cinema Canada in 1985) are collected in Fetherling 1986: 260-336. Hoolboom also made a less known contribution to the debate: “The Cinema We Have: Rumblings from Canada’s Other Cinema,” Innis Herald (Nov. 1986) and Splice (newsletter of Saskatchewan Filmpool – Spring 1987).

15. Mexico, released in 1992 out of material shot around the time of Hoolboom’s pre-Vancouver, pre-diagnosis days, was an ambitious and disturbing exploration of continental politics just as the Tories were pushing through NAFTA, but also an ambivalent immersion in the culture of the bullring and industrial landscapes.

16. The availability of the Hoolboom filmography sometimes seems to be in constant flux: most of the sex diary films, including From Home (1988), Was (1989), Eat (1989) and The New Man (1992, with Anne Marie Fleming) have apparently–symptomatically?– been withdrawn from circulation. Still in distribution are two (1990, with Kika Thorne) as well as Man (1991, with Fleming).

17. Hoolboom currently does not publicly acknowledge a fixed sexual identity, but this feels as much like queer fluidity as coy evasiveness. At Concordia University, 25 November 1999, a journalist asked him publicly whether it is true that he is straight, and he deflected the question with a big grin, hip motion and “I wouldn’t say straight,” drawing out the final word in a three syllable phonetic performance of butch camp.