Making an Approach (September 2013)

It began by accident, I can’t underline the importance of that factoid. How to create a practice that might be open to accident, instead of being modeled after so-called conceptual practices where first thought/best thought decisions are introduced in order to foreclose unwanted vulnerabilities? The year was 1996 and Phil Hoffman and I decided to take a road trip south to see Mike Cartmell. Is Mike a friend? Surely, though he knows nearly nothing about me. He’s so smart I just try to keep him talking in hopes that some of his intelligence will soak into me via osmosis. His second marriage had ended suddenly and catastrophically and after being summarily ejected from his Alabama home he wound up shipwrecked in a Buffalo rooming house. We drove south with vague notions of cheering Mike up, though perhaps we were the ones requiring cheer. When we arrived at his derelict east end digs, I remember him saying that I looked “remarkably preserved for my age” which startled me a little because I had recently gone on the life saving cocktail of drugs that had kept me alive as a cyborg. Though Mike didn’t know it at the time, “preserved” was an apt word for how I was experiencing myself at that moment.

Through much of the eighties I rarely travelled anywhere without a camera of some kind in tow, today’s telephone cams make this a commonplace of course, but back then it was rarer to lug around a wind-up 16mm camera in your knapsack. Phil was part of this tribe of diarists (shoot first, ask questions later), so sure enough, in a gesture of recollection and solidarity, he had brought his never-say-die Bolex camera with him, loaded up with a roll of high-speed, black and white film. When we found Mike cheered by our approach we issued some mutual updates and storytellings and then it was time to haul out the camera. The light in Mike’s grim rooming house was predictably low, but Phil estimated that if we ran the film through the camera three times, there would be enough accumulated light to make visible pictures. Instead of the invisible pictures we preferred to present to each other.

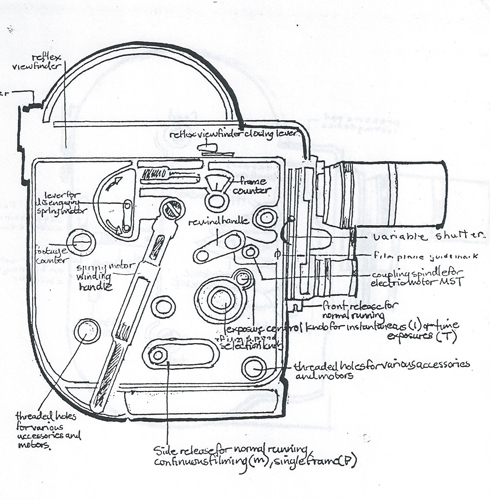

Camera

The Bolex is an interesting camera to work with because it’s not motorized. You have to disengage the crank handle, then line it up with a notch on the camera body and begin winding up the spring. Each wind lasts about twenty eight seconds, though as cameras age the usable part of the spring shortens. In order to rewind the film, the spring mechanism is disengaged, and the film is manually rewound through the camera with a handsome little key. These gestures of cranking and rewinding add considerable time to the operation of shooting, creating spaces where inspirations can condense, necessary pauses and built-in reflection periods collect in these time oases. They are rest stops that help create an approach to the image.

One of the qualities common to many analog devices is that they require some form of twiddling or adjustment or loading before they can carry out their operations. The digital camera, on the other hand, is “always on,” and produces pictures before the picture maker can see them. There is no space before the picture, just as the camera is always on, the picture is always already there, and only part of a web of pictures, a temporary selection from infinity. I don’t mean to suggest that in the good old days we used to make approaches to our pictures, whereas now, in the sordid digital present, the artless, anyone-can-do-it machines do all the lifting. Each technological moment has its own inclinations, its own forms. This is part of what it means to know the procedure, to know your form. Isn’t this how we began as artists? With the injunction to “know your procedure.” The procedure in analog, photo-chemical cinema required making an approach to an image. What does it mean to make an approach? Perhaps it means that instead of the image arriving all at once, there is some necessary prelude to picture making that must be undertaken. This can happen in many different ways of course. Winding and rewinding the camera are only a couple of ways an approach can be made, loading the camera is another. And the drive that Phil and I took to Buffalo is another way of making an approach. We wouldn’t bring the camera out until we had found our way to the necessary place, it was only when the three of us were together that a picture could be made. Our drive to see Mike was also a pilgrimage to a place where the making of pictures was possible.

Approach

“When a painting is lifeless it is the result of the painter not having the nerve to get close enough for a collaboration to start. He stays at a copying distance. Or, as in mannerist periods like today, he stays at an art-historical distance, playing stylistic tricks which the model knows nothing about.” [i

Why is it necessary to speak of making an approach, what difference does it make? I believe that today many movies are made without any pictures in them because people don’t know how to look at what they are seeing. This is what Berger names (in the above quote) as “a copying distance.” If you don’t know how to look at a face, then you can’t make a picture of a face, all you can make a picture of is your inability to look at a face. The camera is pointed in the direction of its ostensible subject, but without a sensitivity to light, without some understanding of how framing excludes more than it includes, without an intimacy above all that flows from both sides of the camera, pictures are created that are only decoys, or false fronts. They may resemble their subjects, but offer little depth or understanding. The artist “stays at a copying distance.” What the phrase implies is that the question of portraiture is a question of distance, of finding the right distance. In other words, portraiture is a question of ethics.

What making an approach offers (but does not guarantee), is that the picture can be made from both sides of the camera, in stereo. In order to have depth, pictures require stereo, which means that the portrait is not only something on the other end of the camera’s lens, but that the subject also looks back at the picture maker. There is a double look, and a picture with depth and dimension arises out of this exchange, this relationship. When a picture stays at “a copying distance” it is trying to remove the possibility of relationship, it is trying to take the place of relationship. Tourist photographs function like this. Instead of having an experience, I can have the picture of the experience I might have had. Tourist photos mark the instants the picture maker leave their body behind. The camera is shield and barrier. A lot of the pictures used to accompany news broadcasts are similar, there is neither the time nor the inclination to look at what is happening in a situation, so pictures are offered in a hasty monotone rhythm (as if every situation were the same), from a copying and touristic distance. That’s why you can see a city or a face on the news hundreds of times, but have no idea of what it looks like until you are face to face with it.

When I write “picture” I’m including sound as well, the conversation that Stephen Andrews and I had that anchors Buffalo Death Mask is an example of this stereo seeing, an exchange of viewer and viewed. Not a monologue but a conversation, a double seeing or hearing. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s go back to Buffalo.

Face to face. After Phil and I made our highway approach to Buffalo, after Mike made his approach via the ending of his marriage and moving across the country, after we had wound up a camera that newly belonged, owing to Phil’s unflagging generosity, to all of us, after we had made all of these approaches we were ready to make pictures face to face. Like every rooming house I had ever lived in, the rooms were small, cramped enclosures, and Mike’s penchant for reading was amply in evidence as books spilled out of every corner in every room. People with money are permitted to live their lives at a distance from others that can be negotiated. People without money live face to face, so here we were, having digested our approaches, but not each other, ready to begin filming. What would we film? Well of course, we would film each other. I remember Phil winding up the camera and handing it to me, and I waited for a moment before turning back to Phil and beginning to film him. We handed over our faces with our cameras. The rooms were so small that most of the shots were made in close-up. And we had the courage of our approaches to bolster us, and it helped not a little that we had a cover story about making a film, or at least, we had said yes to a collaboration of exposures.

When the camera’s spring wind was up I passed it along to Mike. Perhaps he focused on the smoke, or Phil’s fingers, or my face. When his wind was done the camera returned to Phil. We weren’t in a hurry, we weren’t trying to get anywhere, or tell a story. We were trying to stay with each other in this room, in this moment, but instead of the flowing back and forth of language we would use our camera gestures, our faces, our bodies which were already turning into pictures.

Later

The next thing that happened in the film’s making was the most unrepeatable and most important part of all. After the film was shot it was processed, and put in a bin and left alone for nearly twenty years. The exposures made that night were part of a process of gathering time, of allowing time to accrue on a length of acetate and emulsion. The filmstrip is not only a record of time’s passing, but a physical object that bears the marks of time itself, of processing and aging. This time gathering offers many gifts, and chief amongst them was that it enabled me to forget about any impressions, intentions, or interpretations attached to events so long ago. I could watch the footage as if it was made by someone else.

When I reviewed it at normal speed it looked like a shaky, hippie flick, filled with cosmic superimpositions of faces and light that careened from one side of the screen to another. It appeared as a chaos of fragments, as if we were rushing across the rooms of our lives. There were three pictures unrolling at the same time because of the in-camera superimpositions, and these multiple overlays added to the experience of too muchness. And because so much of it was shot in close-up, the camera jammed right up tight to these faces, they appeared inescapable.

Twenty years later, I asked Phil for the roll when I was making Lacan Palestine (2012), a movie where Mike appears as a Lacanian expert rolling out personal asides and theoretical implications. When I watched the roll (it lasts just two and a half minutes) projected I felt it was unusable for the project. But when the endless edit sessions of Lacan Palestine were done (once again I had to race to the end, and start over, and race to the end, and start over, and bring the music in, and bear up to their slaughterhouse remarks, and then begin again, over and over, cutting day and night for years) I returned to it. There was a kind of haunting involved, a ghost whispering, that asked me not only to see it again, but to see it again for the first time. Only this time I ran the footage in slow motion.

Slow

What I had learned in the past twenty years, reluctantly as usual, was how much time it can take to make an approach, to see a face, or make a portrait, which meant also allowing my face to be looked at, to collaborate. These collaborations, between a forgotten material and an artist, or between a pair of artists, can take time. In “real time,” projected at twenty-four frames per second our faces were a blur of accelerations, a speed mirage. In order to see what was actually happening inside them was to slow down the pictures. The technique of slowing is not a stylization introduced later by the artist, it is a documentary gesture, a necessary technical intervention that wipes the window clean so that we can see through it. The so-called “real time” of these pictures produced a blind, it was only by removing this blind, and rendering these frames at hyper slow speed, that I could at last see these faces as they actually were. After twenty years they had been retrieved.

Material Capitalism

These newly slowed frames are attached to the project that consumed us at the Funnel, that we might look into the machines of cinema in order to reformulate capitalism itself. In what is arguably the most famous essay in the twentieth century, Walter Benjamin argues that the cinema is an instrument that can be used against capitalism because of the way it renders time, its “unconscious optics” create new spaces of resistance to the capitalist project. The structuralism of Malcolm LeGrice is an extension of the project that Benjamin laid out in his seminal essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936), particularly in the following passage that I’d like to quote at length.

Walter Benjamin: “By close-ups of the things around us, by focusing on hidden details of familiar objects, by exploring common place milieus under the ingenious guidance of the camera, the film, on the one hand, extends our comprehension of the necessities which rule our lives; on the other hand, it manages to assure us of an immense and unexpected field of action.” [ii]

When Benjamin writes “unexpected field of action,” he is giving us a picture of a battlefield, the battlefield of everyday life, that the motion camera is going to intervene into, creating new spaces dedicated to “action,” meaning, the work of anti-capitalist activity. He goes on to describe a system of economics that has ruthlessly penetrated every aspect of our living, and holds up the cinema as a possible defense against these incursions.

Walter Benjamin: “Our taverns and our metropolitan streets, our offices and furnished rooms, our railroad stations and our factories appeared to have us locked up hopelessly. Then came the film and burst this prison-world asunder by the dynamite of the tenth of a second, so that now, in the midst of its far-flung ruins and debris, we calmly and adventurously go traveling.” [iii]

The hierarchical duo of boss and worker have turned the gathering places of urban life (bars, streets, offices, furnished rooms) into “prisons.” They are enclosures which have been constructed in order to subject citizens to a bio-politics of scheduling, a “standard time” of strict temporal ordering. And what might release us from these schedules is a device that will re-orient (or dis-orient!) the time of these spaces. Because film is exposed at a very rapid rate, twenty-four times per second, it is able to see what the eye cannot see, and via its careful, frame-by-frame review, we might be able to see what lies in the in-between moments of our lives, and thereby rescue them, liberate them.

“With the close-up, space expands; with slow motion, movement is extended. The enlargement of a snapshot does not simply render more precise what in any case was visible, though unclear: it reveals entirely new structural formations of the subject.” [iv]

Here Benjamin announces the aim of cinema, which structural cinema was delirious enough to take up in earnest. For Benjamin, cinema is concerned with the formation of the subject, the viewer in other words. New kinds of seeing would create new kinds of seers, new forms were necessary to break us out of the perceptual prisons of our streets and workplaces. The piece that structural cinema would add to Benjamin’s formulations was its insistence that the machinery itself would show us how we as subjects were formed, and if you can swallow this then it logically follows that viewers could then be re-formed right along with the radical re-forming of pictures and sounds. It wasn’t simply a question of making movies differently, the liberationist project insisted that these different movies would create different people.

“The act of reaching for a lighter or a spoon is familiar routine, yet we hardly know what really goes on between hand and metal, not to mention how this fluctuates with our moods. Here the camera intervenes with the resources of its lowerings and liftings, its interruptions and isolations, it extensions and accelerations, its enlargements and reductions. The camera introduces us to unconscious optics as does psychoanalysis to unconscious impulses.” [v]

In Buffalo Death Mask we see a hand reaching towards a light. We can see the flex of each finger as it opens in hope and towards possibility. It is a hand bathed in light, refinding itself in incandescence, warming itself, relearning its fundamental gestures of grasp and release. What is mine, and what is not mine, what is okay and acceptable and what I believe in, and what I reject. We see a hand opening and reopening. These glimpses of opening are what Benjamin names as “unconscious optics.” In their newly slowed state, these film frames show us, or this is the hope, something about the way a hand operates, something about the nature of this hand. In other words: the physiological roots of desire, of grasping.

Benjamin writes about the way space expands via a close-up, how this expansion and re-orientation of spaces could create new vantages from which to escape the duty and utility of our bodies and faces. Buffalo Death Mask slows down a few gestures of the face as a pair of eyes open, as Mike’s face smiles and passes from one side of the frame to the next, as a smoke ring forms and dissolves in his mouth, his entire face wreathed in smoke, dissolving. Could we reconceive “the project” of the face from these few glances? Are these faces refusing the rush of time, the fantastical acceleration of pictures newly available online, are they offering places to rest the gaze, and to scan across the entire surface of the frame, refusing the centering typical of most informational imaging? Is the ability to scan across the surface of a picture itself a political act, or could it be? What does it mean to recast a face in this new time, and to create this time for a queer inquiry into an epidemic that many feel is already over? Are there ways that these faces resist summary and sound byte, that they create a newly necessary time that makes a certain consideration of faces and portraiture, of time and seeing, of grieving and identity, possible?

AIDS

The AIDS crisis asked each of us so many questions, including: what is my body? This illness was not like other afflictions or viruses that would be hosted inside the body for a time, this was an illness that had come to stay. Am I the AIDS virus? Where does my body stop and the virus begin? BDM’s hand reaching into light poses similar questions about perimeters, boundaries, separations. What is not this body? What does this body not contain? What could possibly be separate from it, now that it has been touched and stained and reconceived by this ingenious virus, that has linked so many of us around the world in a common cause of sorts, as if we were all parts of one body. Is the hand reaching out trying to escape its fate, its status as a hand that has AIDS, that is AIDS? Is it a hand reaching out to other hands, in solidarity, a hand longing to touch, for one more kiss, as Jarman says with such solemn lightness in his AIDS memoire Blue (1993), in which a blue screen (he had gone blind recently, the film features simply the projection of a blue screen and a dazzling series of voices and sound treatments, offering a curious echo of my own White Museum (1986), made half a dozen years earlier, which was similarly comprised of a blank screen and voice-over) offers us a documentary corollary for the filmmaker’s seeing.

Interdependence

The central trope of the original 16mm footage we shot in Buffalo is superimposition. There were several passes of the original strip of acetate through the camera, in order to ensure there would be enough exposure, so one picture was made, and then the camera was rewound, and then a new exposure was made over the old ones. The light builds slowly across each frame, on each pass, and as it does it ensures that bodies are rarely seen in isolation. It is so often our bodies together. Even when it appears that the frame is offering a view of, for instance, a single face, or a single hand, buried in the white light of the “background” are pictures of other faces and hands. Most often though, the frame offers an image of interdependence, a shattering of boundaries, the same way that this illness breaches the body’s traditional boundary of the skin. Newly reconvened inside the camera, we became parts of each other. The cinematic treatment mirrors the effect of the plague that is no longer rendered as tragedy but solidarity.

And what was only too clear now that the footage was slowed was how each of us was moving unmistakably towards our own death. Does that seem too heavy a throw down? There is a distinctly funerary air about the proceedings, not only that, these faces do not appear, to me at least, to be looking back from the past, instead they are looking back from the future, from the moment of their own death, when each face is dissolving into light.

In the cinema slow motion is usually used to arrest a gesture, to take some quickly moving form and render it weightless and allow us to see the intervals that comprise each apparently seamless moment. In Buffalo Death Mask there is constant movement in the slow motion, but what is being slowed down is rarely a gesture, only the smallest of inclinations, the opening of the eyes for instance, or a smoke ring being blown, or a face passing from the bottom of the frame to the top. And what is being seen, in each of these instances, is the way these bodies are dying, are moving towards their own death. Jean Cocteau famously quipped that in the cinema one watches death at work, and I think it is particularly true in this movie, where you can feel the weight of the body, the mark of the years already passed, the slow rapture of release and final succumbing.

Light

After I became positive (aka seroconverted) I learned how to look in a new way. Not because of the new divide between those who were and weren’t positive, or because of whatever ideas separated the dying and merely unwell from the robustly healthy. I’m speaking in a physiological sense, at the level of sensation and perception. I learned in those years, surrounded by so many who were dying, to be able to see how a body ages and dies in a single instant, the same way a speech glitch or a yoga posture or a DNA molecule synthesize generations of inclination. I learned to see the way that light came from bodies, as well as falling on them. Our dying selves emitted a very particular quality of light that I learned to see while sitting in the waiting rooms of Vancouver General, where an entire generation of men had turned into the walking dead. They were sad and angry and defeated and undefeated and beautiful and terrifying and each emitted a light that I could see when I could get over the sheer difficulty and terror and mirror-holding prophecy that each of us became for each other. We were a promise for each other. Today it’s me with the facial lesions and the cane. Three months ago I was bench-pressing four hundred pounds, now I can hardly get out of bed. And one day, only too soon, it will be you. But out of the chests of these cane wielders and bent-over skeletons there was a rare and beautiful light that I learned to trust and was able to find more reliably as the frequency of my visits increased, and I became involved in the local version of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power).

Many of the images of Buffalo Death Mask feature this quality of light, they show light coming from the body, and this, more than anything, is what I wanted to share with the film. In fact, in its earliest versions, which lacked any dialogue, the hope was to concentrate the eyes so that they could be trained in these twenty minutes to be able to see what I had learned to see, that the movie would act as a secret workshop for anyone who would watch it, and show viewers what it had taken me a fatal illness to discover. That our bodies transmit light. But when I ran it for the music (Gary and Steve) they assured me that they couldn’t see a thing. Yes, sure, there were moments of beauty, but they remained far away. Why should we care? This is what they told me. Turn these faces into something that matters. Apparently, these pictures needed the company of words. As usual, I had come to the end, only to find myself returning back to the beginning.

Starting Again

The fantasy was purity. I had hoped to make a single gesture, with a single roll of film shot decades ago slowed and reviewed. And this purity was also a salve to my need to Always Be Closing, to find my way to the end of a project as soon as it was beginning. So I recognized immediately what they were saying to me, that the project had an obstacle that I couldn’t see, and the obstacle, which like all obstacles was designed to show me what I really wanted, was language. I was holding onto my silence, only to find that what these pictures needed in order to be seen was a relationship in language. There were going to have to be words. But whose? And how?

Stephen

I knew I wanted to have a conversation. What I hoped for most of all was to have some breezy speaker hold forth in a groove that would be at once personal and philosophical. There was only one person I could think of, and that was Canadian artist Stephen Andrews. Incredibly, he has been positive even longer than I have, and if I write “incredibly” it’s because there’s not so many of us left from that time. And it had been only too clear for some years now that like me, he had learned to see the particular quality of light from bodies that were dying. In fact, Stephen’s work, whether his more recent painting forays, or his faux film strips, or his painstakingly rendered animations, are filled with this seeing. Over and over again his subjects were turning into light, becoming light, dissolving. It was as if we were working on the same project, but with different tools in our hands. I didn’t really want to ask him about this though, what I wanted to find out, most of all, was how he survived the afterlife. I knew, or at least I could imagine, how he might have reconciled himself to an early death. What I didn’t understand, the cover story I’m still looking to absorb, is what Stephen names “the Lazarus story,” when a cocktail of pharmaceuticals brought some of us back to life.

We set a date and I showed up one sunny afternoon without much sense of what we might say, or the important questions I should ask. To be honest, I hadn’t thought a lot about what was going to happen, though I had approached Stephen before, and saw the frank reluctance he showed to be involved in any project involving pictures that were not his own. I think the fact that I came with a tapeless tape recorder and no camera was a big plus. It’s not simply aging that we are wearing on our new faces. The life-saving cocktail has a nearly universal side effect named lipodystrophy which redistributes the body’s fat. It sounds like a good time at first, at least for the calorie counters, this drug combo not only saves your life, but it slims away the pounds. For the unfortunate few (and Stephen is one of them), it produces a pouch-like sack of fat in the stomach or the back of the neck (very attractive). Liposuction surgeons have reported that it is a lot like fat, though not quite fat. Fat-like at the very least. Stephen, like many of the similarly afflicted, is big on ab work, but has a little pot belly as if he spent his afternoons swilling beer and eating pizza. Lipodystrophy produces a telltale face that is drawn and shrunken, those of us on the drugs can see right away its effects on the faces of strangers, our faces have been marked so that everyone in the tribe can recognize the signs. Like many others, Stephen had cheek implants laid in, a popular measure for restoring some volume to the face. But this is all to say that cameras are not a friend to our crumbling architectures.

When we spoke it was clear that I wasn’t going to be able to sit back and lob questions at him. In fact, as he immediately rang up queries in my direction about how many drug regimens I had been on, it became clear that if I was willing to speak with him, to have a conversation, a dialogue, then he would hold up his end. What we weren’t going to do was any sort of formal interview.

Stephen spoke about many things, including the light which he had learned to see at a moment very close to the end of his old (pre-cocktail) life. His partner Alex Wilson had died of AIDS, a slow diapers and dementia death where Stephen was numero uno caretaker, even as his own defenses were crumbling. Stephen’s blood counts had begun to plummet, and he was close to death. He had begun to see magical Toronto media artist John Greyson who invited him to take a canoe trip to the Charlotte Islands. It looked like a last gasp, a final trek.

Stephen Andrews: “Everyone was pissed off at John because we were going kayaking for two weeks off the Queen Charlotte Islands. I was of the mind that you might as well go to heaven first and then die. Who cares? This was obviously unfair to John, but he seemed to be a completely willing victim, in case I croaked. What I didn’t tell him at the time was that huge chunks of my vision had gone missing. The visual field had holes where there wasn’t any information. And because I was on Septra and we were outside all the time, I turned red as a lobster.

We had an amazing trip. We had been out in eight foot swells on the Hecate Strait. The waves were too big on the shore to put in anywhere so we wound up paddling forty kilometres that day, and pulled in near Rose Harbour just as the sun was setting. We turned into the strait facing into the sun, and I had a strange hallucination where ‘going into the light’ wasn’t about dying, it was about coming out of darkness. It completely retooled my thinking about what was going to take place. I thought: ‘I’ll go home, take the drugs, and be ok. It’s not a shutting down, it’s an opening up.’ I was completely convinced of this, it was a very beatific moment.” [vi]

We might have spoken for fifty minutes or so, perhaps an hour at most. The point was not to have an exhaustive record of every AIDS moment we could summon, but to let something live between us, and to bring a piece of that living onto the tapeless tape recorder. Stephen and I spoke candidly with one another about the drugs that kept us alive, the moments when we might have become positive, the death of loved ones. Being positive for so long provided a kind of gold card of intimacy, we could instantly step inside some of the most difficult places together with some understanding.

Collaboration

When John Berger writes about portraiture he talks about it as a form of collaboration, and that the art of an artist is the art of receiving. “The modern illusion concerning painting (which postmodernism has done nothing to correct) is that the artist is a creator. Rather he is a receiver. What seems like creation is the act of giving form to what he has received.” [vii] That afternoon, with the portable digital recorder lying between us, Stephen and I did the work of collaboration, of giving and receiving, attuned to one another, finding a form of speaking that lay in the back and forth of the flow between us.

Lazarus

Our chitchat was cut into two parts for the movie. In the first we speak about drugs, Stephen’s former partner Alex, and the way friends are a living form of memory. When the voices return, after a dreamy impressionistic interlude where crowds of light gather together, Stephen talks about coming back to life, his Lazarus moment. It was only when he could let himself be loved again, he says, that he could find his way back into the world. It’s corny until you’ve lived it and turned it into something firm and foundational. I’m still hoping the day might come. Or is it something only the night can bring?

Lazarus was a man that Jesus brought back to life, at least according to the gospel of John. Wikipedia says: “…the name Lazarus is often used to connote apparent restoration to life. For example, the scientific term ‘Lazarus taxon’ denotes organisms that reappear in the fossil record after a period of apparent extinction; and the ‘Lazarus phenomenon’ to an event in which a person spontaneously returns to life (the heart starts beating again) after resuscitation has been given up.” [viii]

The figure of Lazarus has obvious and necessary affinities with the project of cinema, which is likewise concerned with the project of reanimation. The material has already been filmed, it lies inert and unmoving as an object on a film strip or a digital file. Successive pictures stranded on an unmoving island of emulsion, or as a still pool of ones and zeros. But when it is rapidly unspooled on a projector or laid into a media player, these pictures jump into motion, or at least, the illusion of motion. As if they had been granted a second chance to live. The act of filming is a kind of entombing, a funerary rite of embalming, a way of preserving a passing moment. And via the projector, the twinned double of the camera, these remains are raised once more raised to light, and restored to life.

In the early 1900s, an early placard advertising the brand new invention of cinema announced that with the advent of colour and sound, movies would ensure that death would be no longer final. Here is the project of cinema most boldly announced: it was a machine that could defeat death by tirelessly reinvigorating moments of the past. And you can imagine how important that might have been for me all those years ago, before and after the arrival of the unwanted chemical rescue squad. I was also trying to reanimate myself through the not inconsiderable haze of fatigue and duress, and to preserve some of the too many sensations so that others might understand a jot of what had gone down in a generation marked by plague.

A.A. Bronson writes in his memoir Negative Thoughts about the two men he loved, his comrades in General Idea. Bronson: “In 1994, when Jorge and Felix were dying, I convinced myself that I was dying too, that the HIV was latent, that I had symptoms of illness, that my grief together with my desire to die would rot me through with cancer. I thought through my life as they thought through theirs, and we wrote our wills together. I came to a point of completion, a sense of satisfaction. I was able to say, and did: “If I die tomorrow, I will have lived a full life.” I was ready to let go.

But life did not let go of me. It forced me to suffer.

Jorge died, and then through the fog of grief, five months later, Felix died too. I was sitting with him. I said to him, “Felix, It’s OK, if you want to go now you can.” He looked at me uncomprehendingly and fell into a small sleep. I went to refill my coffee cup and when I returned he was gone.

What is there to say of death? We live and then we die. While we live, we are surrounded by the dying, and by the dead. We are all dying. And the dead walk among us, surveying our decay.” [ix]

Portrait

At the film’s beginning the multiply superimposed roll of Buffalo faces appear in slow motion, and as soon as Stephen finishes talking they reappear, bookending the movie. Between them are pictures drenched in light, moving forms of what might be Stephen’s paintings. I needed some pictures of him, what I was hoping for most of all were images of him at work, and he agreed to make some, providing he could do it himself. He used his iPad. These were collaged with images of Stephen from an early John Greyson movie called The Perils of Pedagogy (5 minutes, 1984). It was made years before they became partners (Stephen was still with Alex at the time, his boyfriend who died of AIDS), and shows Stephen as an impossible beauty dancing in a variety of bracing outfits as To Sir With Love lays down the backbeat. I wanted to recast into a single frame these prophetic outlines of Stephen’s pre-AIDS self, as seen by the man who would bring him back to life, and layer them into auto-portraits that would show him drawing pictures of John, forming a circuit that would short-circuit thirty years into a few seconds.

Here is Javier Cercas in his modernist Spanish masterpiece of a novel, Soldiers of Salamis, in a scene where an aging communist looks back at his war years and the village comrades he lived and died beside. “Sometimes I dream of them and I feel guilty. I see them all: intact and greeting me with jokes, just as young as they were then, because time doesn’t pass for them, they’re just as young, and they ask me why I’m not with them – as if I’d betrayed them, because my true place was there; or as if I were taking the place of one of them…” [x]

I have thrown away nearly everything I’ve shot on film, many years of spontaneous gatherings and calculated emission tests. One of the few remnants from this twenty year period of making is a visual diary of my shingles illness, back in 1995. Stephen mentions shingles as a definitive sign of the passage from being HIV-positive to AIDS (in other words, he is not only infected, but symptomatic), and I was surprised to hear that he put such weight on this particular illness. I had also had shingles, but it didn’t seem more significant than the pneumonia that I caught twice, and that was such a reliable killer in those days, or mono, or the host of other illnesses. But Stephen’s shingles recollections lured me back into the archive where I could reanimate those long ago days and nights. It became a helpful underlining, showing my pictures with his words, a demonstration perhaps that the virus had produced new lines of interconnectivity and connection, new flows and circulations were possible. It’s your mouth and my body, or perhaps a language of the body we held in common.

Memory

In his typically droll and elegant fashion, Stephen Andrews (in the movie) speaks about the double death that occurred when Alex Wilson, his lover and comrade for a decade a half, passed. Stephen: “Not only do you lose them, you lose what they remembered about you. And if you don’t fully understand yourself, then you’re doubly bereft. Suddenly you start to feel the hollowness in yourself because you had it backed up with these people… if you don’t have these people who know you, then who are you?” [xi] What Stephen underlines is friendship as a living memory, the way we hold pieces of one another in our bodies. I used his speaking in this instance as a kind of script, and began to gather pictures of friends, shooting in super 8 to give the images a grainy, impressionistic hue, and searching for the qualities of light that appear again and again in Stephen’s artwork. While Buffalo Death Mask is sparing in its use of landscapes, settings, faces, concentrating attentions on just a few moments, this section opens up into a quickly cut montage, a suggestion or pointer to worlds outside the film, of other lives. With these words and faces, the movie tries to extend the AIDS narrative to non-positive friends and family, wider circles of acquaintances are also part of the story being told. It is a summoning of interdependence, an insistence that the body does not stop at the skin, but runs through memory, language, shared experience, affect. I am your mouth when I taste the food you make. I am your “back up” hard drive recall for a night when you were too staggered to put the pieces together. The self reappears as a social body, as a collection of pieces, hence the fragmented quality of this section.

This movie is a double survivor’s testament, a duet. In its back and forth exchangings it hopes to summon the outlines of a community, a group of people aligned with post-capitalist values, who had survived a certain death by becoming cyborgs, by admitting an incessant pharmaceutical regime that reshaped our bodies. You only live twice, was this the plague motto for the first worlders fortunate enough to have access to meds? Our lives had detoured around normative narratives of marriage/job/child rearing. And from increasingly marginal perspectives, we tried to resist what Sarah Schulman describes as a post-AIDS “gentrification of the mind” (in which a heterogeneous complexity is replaced with a moneyed middle/upper class uniformity). [xii]

New Generation

And what of the new generation of seropositive conversions? I was floored after speaking with Cheryl, she is Dr. Cheryl to many, who has an all–HIV practice in downtown Toronto. She was describing a young man who had recently become positive and came to see her. The strangest factoid was his address: he called Barrie home. I couldn’t help asking: “Why did he come and see you if he lives in Barrie?” (It’s an hour and a half drive away on a featurless mega-highway) Cheryl replied, “Because he can’t take the risk of being seen in a doctor’s office. He doesn’t know anyone who is positive, there’s no community, he’s completely in the closet.” As soon as she said the words I realized what a privileged bubble of a community I live in. I can be an ‘out’ positive person without having to negotiate the labyrinth of societal disapprovals that this young kid will have to manage.

The hope in making this movie is to try and extend the sphere of privilege, or normality, or sanity, so that others like him can be seen as people, instead of being reduced to an illness, a condition, a tagline. For most of my friends, I am the only positive person they have ever met. And similarly, this movie has been shown (so far) largely in contexts of large international festivals, or else experimentalist festivals, where this film is the only one addressing questions of positivity, where there are few queer movies at all. The people who see it are not part of the lifelong conversation that Stephen and I have been having with everyone around us. This, I have to believe, is a good thing. The point in all this is not simply to have the same chitchat with the same people.

The old liberationist dreams of the avant-garde have been repurposed as the project of fringe movies has become increasingly professionalized. If we once longed to become artists, today a new generation longs to become curators. There are too many artists now, too many movies being produced, what difference can any of it make? For now my work travels across familiar circuits of movie festivals and cinematheques, occasional classroom screenings and libraries. It is still committed to questions of formal difference and political portraiture, creating space for marginalized lives with roots in personal experience and expressions. And while the AIDS crisis may be “over” for some, each year there are millions of deaths, and many tens of thousands of seroconversions, and countless instances of bigotry and misunderstanding. This movie is a small attempt to stand in solidarity with the men and women who are living and dying inside these plague years.

[i] John Berger, The Shape of a Pocket, (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2001), 16.

[ii] Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, (New York: Schocken, 1969), 223.

[iii] Benjamin, 236.

[iv] Benjamin, 236.

[v] Benjamin, 236.

[vi] Mike Hoolboom, “Life After Death: an interview with Stephen Andrews,” unpublished, 2013.

[vii] Berger, 18.

[viii] “Lazarus of Bethany,” Wikipedia page, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lazarus_of_Bethany, September 2013.

[ix] A.A. Bronson, Negative Thoughts, (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 2001), 50.

[x] Javier Cercas, Soldiers of Salamis, (Barcelona: Tusquets Editores, 2001), 198.

[xi] Stephen Andrews, voice-over in Buffalo Death Mask by Mike Hoolboom, digital cinema, 2013.

[xii] Sarah Schulman, The Gentrification of the Mind, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012)

Being Loved Again

Stephen Andrews and Mike Hoolboom in conversation, August 2012

When I arrive at Stephen’s the new front door opens to a nearly empty house, boxes are stacked discretely in corners. He’s just back from an epic global trek with his partner John, and the architects have been busy knocking down walls. Afternoon light pours through the windows. He greets me with an easy smile, his head slightly tilted back as if raised on some permanent perch of bemused ironic hilarity. His droll speech bristles with wit.

I plug in the tape recorder and promptly forget to switch the microphone tab to the correct setting, meaning that the five star instrument I’ve brought to record the session never channels into the recorder, instead the very average, built-in mics absorb the room. Will I never learn to speak the language of machines? I’ve been working with pictures that remind me of Stephen’s paintings, luminous bodies glowing in a light I had learned to see a long time ago, back before the mega pharma companies dished up a combination of drugs we called the cocktail. When the magic elixir arrived, those of us on the way out began a slow crawl back from the exit door. We had been relieved of that certainty as well. I wanted to put a couple of questions to Stephen about that long moment, though as usual had come unrehearsed.

Mike: I discovered pine beetles in my apartment. Tiny specks with legs. They’re not bedbugs, they’re not cockroaches. They don’t bite you.

Stephen: How do you know they’re pine beetles?

Mike: I looked them up. And then my maintenance supervisor dude from the building came by and announced, “Pine beetles.” “Should I be worried about that?” “No, you’ll just clean everything here, everything. And it will be fine.” I threw out 22 years worth of HIV-medication bottles.

Stephen: How come you’re saving them, are you a hoarder?

Mike: No, it was the only thing I’ve saved.

Stephen: Empty pill bottles?

Mike: I thought one day I would do something with them. And one day never came.

Stephen: Well it’s interesting because those things have all changed, right? They go in and out of fashion as you wear them out. What number of cocktail are you on? How many have you used?

Mike: Not many.

Stephen: Really?

Mike: I think I’m on number four.

Stephen: I’m on four or five.

Mike: That’s not many.

Stephen: Over a ten year period?

Mike: Ten years?

Stephen: No wait, it’s more, sixteen years. The drugs came online in 1996, right? September 1996. I know because I was just about toast. CMV (cytomegalovirus) had started and I weighed almost nothing. I was a total disaster area. I jammed my foot in that door as it was closing. I started the drugs when I got back from kayaking with John and went on medication the next day. They didn’t work for the first month, I felt just vile, and then on the thirtieth day the light started shining again. (laughs) I was riding in a car and felt strangely happy, which I hadn’t felt in quite some time. I thought, “Oh I don’t feel like projectile vomiting.” It’s amazing what that does for your sense of well being. (laughs) I was on Saquinavir which was not the best of the drugs.

Mike: None of the early drugs were the best.

Stephen: And then I went onto the wasting ones, like 3TC and DDI.

Mike: Norvir, that was also called something else.

Stephen: They always had two names, I’ve never really understood why. It’s like an alias.

Mike: It’s so that the parents can talk together and the kids won’t know what they’re saying.

Stephen: I’ve given up on the names. They ask me sometimes, “What are you on?” and I have no idea. It’s like, you know, you’ve had so many lovers you can’t remember all their names. (laughs) I’ve been on so many drugs, whatever. What’s your name again? Norvir? DDI? Yeah, I’ve been sleeping around with them all for quite some time. Just like you. When did you seroconvert?

Mike: 1988.

Stephen: Do you know that for a fact?

Mike: That’s when I found out by accident.

Stephen: What do you mean by accident?

Mike: I was giving blood. Afterwards they said: you should talk to your doctor. Do you have a doctor? I said I go to this clinic sometimes. You should talk to someone there.

Stephen: Because they’re not going to take your blood.

Mike: They were vague. They didn’t say anything more about it than that. Then there were a series of frightening events. I remember at 8:30 on a Tuesday morning I got a call from someone in the Ministry of Health. “Hello, is this Mike Hoolboom?” “Yes.” “Hi, this is the Provincial Ministry of Health. So I understand you’re HIV positive. Have you informed everyone you’ve had sex with about your status?” 8:30 in the morning.

Stephen: Can I caffeinate before you grill me? That was 1988, the height of the paranoia.

Mike: People were scared.

Stephen: When do you think you seroconverted? It must have been a couple of years before.

Mike: It’s hard to say.

Stephen: Are you a transfusion guy? Did you get HIV through transfusion?

Mike: No, it would have been sex or needles. (laughs) So hard to decide sometimes. So many people have asked, but it’s hard to imagine what could be less important now. Why would that matter?

Stephen: I think it’s about blame, and not accepting responsibility for your own actions. What was the sequence of events? Did they know? Did I tell them? You tend to forget because it was a tempestuous time. Everything was up in the air and very scary. I could always deflect back onto the loved one. I can worry about you, I don’t have to worry about myself.

Mike: Your lover Andrew you mean.

Stephen: Alex.

Mike: Alex, right.

Stephen: I’m almost positive I seroconverted in 1982 in Haiti, because we had this very wild sex with a fellow by the name of Ti L’homme, who was anything but petit. I can’t imagine it was anywhere else, because the symptoms started showing up in 1985.

Mike: What were the symptoms?

Stephen: I got shingles at the age of 28, twice over the course of two years, in my legs of all places. It’s a weird place to get it, right?

Mike: I don’t know what’s weird with shingles. People get it on their face.

Stephen: Yeah, when they’re 90. Not when they’re 28. (laughs)

Mike: I didn’t get shingles until I was in my 30s.

Stephen: Did you get it on your face?

Mike: No I got it here, on my chest.

Stephen: Isn’t it awful?

Mike: It’s fucking painful.

Stephen: It goes on for months.

Mike: There is the magic of Percocet.

Stephen: Is that where the needles come in?

Mike: There’s no need for needles when you’ve got Percocet. The doctor cautioned, “You’re not going down to the street and sell these, are you?” “Are you kidding me, give those to me right now.”

Stephen: I still have neuropathy from it. After half a bottle of red wine it’s like being plugged into an electrical socket. The nerve damage is still there.

Mike: The body remembers.

Stephen: The disease is writ large across your body in so many different ways.

Mike: Did you know in 1985 that you were HIV positive?

Stephen: Alex was diagnosed with ARC at the time, an acronym for AIDS Related Complex. He was having night sweats and losing weight. Then it just became obvious that he hosted a series of opportunistic infections on and off until his death.

Mike: From the mid-eighties to…

Stephen: Yeah, from about 1986 until 1993 when he died. I think because I’m a mongrel I didn’t get sick until quite late. I have the genetic superiority of mixed blood to get at these things from different angles, whereas he was a thoroughbred and they could take him out right away. But as soon as he died I went down the hill.

Mike: Do you think there’s a relation between his dying and your health?

Stephen: Yes, it’s very depressing losing someone you’ve loved so deeply. This is someone I was with for almost fifteen years, someone I went through all of my changes with. It’s like having your heart ripped out. It was a very depressing time generally, and then I lost both my roommate and my studio mate in the same week. Suddenly you have all this stuff to deal with; a person’s life doesn’t stop just because they’re dead. It was total reality. Everything was so real every day. I was sharing a studio with Rob Flack. I got a call in the morning that Rob was in the hospital. I got a call at eleven that night telling me that Rob had died. You know that story. That’s what we were living with. You could operate, but it really did affect your world view knowing that every day could be your last. How did you manage?

Mike: I was on a countdown. Because I’m an optimist, I thought I would have ten years which would make me, in the words of that time, “a long term survivor.”

Stephen: That was the prognosis. Basically everybody died after three years though. (laughs)

Mike: I didn’t know that. I didn’t know anything. I also couldn’t tell anymore: am I sick? Am I dying today? There were so many days like that. I’m tired. Am I really tired? Am I dying tired? Years later friends told me how bad I looked for so long but they wouldn’t tell me. Why would they tell me? You get used to lower levels of functioning.

Stephen: Yes, because the decline is gradual except for the occasional crisis. You normalize things. And you distanciate. Denial is your friend. People would tell me I was in denial. I would ask them: and what is your strategy for dealing with this? Embrace it? “Oh woe is me, I’m going to die today, or the day after.” No, I’m like you, glass-half-full guy.

Mike: I think I would have found it a lot harder to embrace my denial if I was living with somebody who was in such bad shape.

Stephen: There was too much work to do to care about oneself. There were diapers to change, medicine to pick up, people to phone, arrangements to be made.

Mike: Alex was extremely unwell for quite some time.

Stephen: During the last year I was basically taking care of him eighteen hours a day. I was running his career because his book had just come out, and we had a landscaping business. And then there was my own career. The physical aspect of taking care of him was very demanding. Six months before he died I had to go away. I had an exhibition, and finally I had to leave and install my show. I left him with Colin Campbell who flipped out. He had no idea how much work it was. Alex was an adult but he couldn’t do anything, he had no energy. He couldn’t cook for himself, he could barely walk. Nobody knew until then. Then John Greyson mobilized a care team who took over the day time schedule. We went dancing a lot at Go Go’s, at the height of House music’s popularity, so every Wednesday somebody would stay at the apartment, while I would go out and take drugs and drink and dance until whenever I wanted to come home. Alex had a pajama party every Wednesday so I could leave. It was the best way to get out of your head. How did you distract yourself?

Mike: I overworked. I had a job at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre, so I thought: why don’t I just work seven days a week? It turned out I could share a studio with friends just around the corner, meaning I would never have to go home. Home was a room that was empty except for two milk cartons which held all my clothes and books. No telephone, computer, electronic devices. The important things in my life – film, camera, rewinds – were at the studio. I was forever working on “the last film I’ll ever make.” One after another.

Stephen: It was kind of fabulous, you didn’t put up with any guff. I’d already decided that I was going to be an artist, but this period cemented my resolve. I’m going to die tomorrow, so I don’t want to be caught up doing things I don’t want to do. Life is short, the future is now, let’s get on with it. I got the call early and picked up. So many people work their whole lives and save their money thinking, “I’m going to retire, and then I’ll do all the things I want to do.” Not me. I’m from the hedonistic seventies. It’s all about aujord’hui. Tomorrow is just a broken promise, I’m sure.

Mike: Something they sing about in French songs.

Stephen: Exactly. (singing) Rien de rien…

Mike: I found it hard to be clear about the work I was making in that pressure cooker.

Stephen: You mean the external pressure?

Mike: The internal clock. You’re dying, you don’t have time, finish this now. How can I allow a work to unfold in its own way? It was a difficult moment to learn patience and abiding. I was filled with fear. When I look back on the movies I made, there were plenty of them, but I don’t think they were very good.

Stephen: Have you seen them lately? There’s nothing like urgency. And there’s something so evocative of a moment that can’t be translated into nostalgia. That work carries all the subtleties of its era. So it might be interesting to look at it again, just as a document, because you were responding to things as they were happening, and there’s probably some kind of honesty there, even if it’s the not the most aesthetically pleasing. You can always tweak it digitally now.

Mike: That’s definitely what I don’t want to do.

Stephen: What did you do when you realized you were Lazarus? When they rolled away the stone and said, “Come out.”

Mike: I had a very reluctant relationship to drugs. As my counts lowered, my doctor begged me to go on AZT, the only drug available then, and all I had to go on were my instincts. I refused, which turned out to be a good decision. When the cocktail finally arrived my counts were… I know they’re in there somewhere, if we keep looking.

Stephen: There were so few you could name them all.

Mike: My health dramatically improved, I had the initial “I feel shitty” period too, but it didn’t last so long. That wasn’t the difficulty, as it turned out. I had set myself on a ten year path and it was difficult to let that go. I’m still grieving the fact I’m not dead. In the past couple of years I’ve had several friends die, and part of what makes that unbearable is that it cuts against my deal. I’ll die young, but as the first out the door, I don’t have to watch my friends die.

Stephen: When Colin was dying I felt he was pissed that I wasn’t already gone. He had done all this worrying about me, and then suddenly he was checking out before me. There was a certain kind of animosity directed towards me at the end. It’s something I could recognize because I had other friends who were in the same boat, but maybe not as far down the river, and I became angry, even resentful, at their relatively good health.

Mike: You mentioned a canoe trip with John.

Stephen: That was the trip I described before the cocktails arrived. It was in August 1996, the cocktail came a month later. We had heard rumours at the beginning of the summer about a drug cocktail with protease inhibitors. But it wasn’t clear whether it would be made available in Toronto. And there was no guarantee that I was going to last that long. I promised John when I went on this trip that I wouldn’t get sick, so I was full of Septra and everything else possible to prevent things going sideways.

Everyone was pissed off at John because we were going up to the Queen Charlotte Islands to kayak for two weeks. I was of the mind that you might as well go to heaven first and then die. Who cares? This was obviously completely unfair to John, but he seemed to be a completely willing victim, in case I croaked. What I didn’t tell him at the time was that huge chunks of my vision had gone missing. The visual field had spots and dots where there wasn’t any information. And because I was on Septra and we were outside all the time I turned red like a lobster.

We had an amazing trip. We had been out in eight foot swells on the Hecate Strait. The waves were too big on the shore to put in anywhere so we wound up paddling forty kilometres that day, and pulled in near Rose Harbour just as the sun was setting. We turned into the strait facing into the sun, and I had a strange hallucination that “going into the light” wasn’t about dying, it was about coming out of darkness. It completely retooled my thinking about what was going to take place. I thought “I’m going to go home, go on the drugs, and be ok. It’s not a shutting down, it’s an opening up.” I was completely convinced of this, it was a very beatific moment.

We came home, I went on the drugs, and got better. But what I hadn’t anticipated was the difficulty coming back from that brink. It took me three or four years to put Humpty Dumpty back together again. I had imagined I had finished my (art) work, that it was a good time to go. But when that didn’t happen, how do you start again from below zero? It was time to rebuild a rationale.

So much of my sense of self is about being loved and I had lost my love. I thought: I’m down a pint or two or three. Who is going to love me again? How will I live when I can’t be loved? It was a very difficult moment. It wasn’t until 2000, after John and I got together, that I understood what this Lazarus thing was about, this coming back to life. It’s about being loved again. That became an allegory for the stone rolling back. It wasn’t just regaining my health, but being loved. That’s when I felt alive again in some profound way, and found a new place to work from.

So much of my coping mechanism in the years prior to Alex’s death was about reading Rumi and finding spirituality through love; the physical-emotional love articulated by Rumi. Somehow that had gone missing in my thinking about how to regroup. In 2000 I found Rumi again and his thoughts about seeing oneself reflected in the jewel-like eye of the beloved. That’s when I could make something again that mattered to me, that wasn’t a rehash of old ideas.

Like you, my work defines me; that’s what being alive is, it’s about working. Processing the world through making things. It’s like thinking out loud. Thinking in material ways. You must have gone through some version of that experience to piece it back together again. You described living out a countdown, charging towards an end point. I was doing this aesthetically, and thought about it in mathematical terms. I had done all those AIDS portraits, painting fax portraits that had been made up of zeros and ones. I wondered how that could be further reduced. I was trying to distill experience to its essentials. After taking chiaroscuro out of the line, what is the next logical step? Working at the level of the pixel. And what is a pixel but a numerical representation? So I made drawings using numerical representations. Then you get to zero and there’s nothing left, and that’s why I thought I was ready to go. I had reduced the work down to its endgame, which was a trap that I was going to get out of by dying.

When I came back to life, I started to think of the zero as a lens. Everything goes through this focal point and comes out the other side. That’s when I became even more interested in materials and processes, and understanding that the gift of life is material. I didn’t need to get so caught up in denying oneself materiality. I thought that’s all this is, existence is just stuff. Might as well have more nice stuff. Make stuff, get stuff. John and I would laugh because friends from Portland were telling us about Rajneesh who said, “I believe in materiality and spirituality.” I totally buy that!

Mike: The way you’ve painted light and bodies in the last half dozen years feels familiar to me because I was positive in that pre-cocktail moment. I can’t help feeling that all of us were that light, and I’m not speaking metaphorically. Light didn’t simply appear on bodies, it came from us. It’s amazed me that you’ve been able to take this culture of death and dying and transplanted it, using it as a lens to re-view contemporary events like the Iraq War.

Stephen: Elle Flanders was at a talk I gave and said something similar. I found it shocking at the time. Is that what I’m doing? I thought the work was about life. But you need contrast, you use darkness to describe light. If you look at the paintings, they are given over to describing nothing, the white blank of the canvas. There’s nothing at the heart of the matter. I haven’t done anything to this emptiness, I’ve only described everything around it. It made me think that the earlier work, which was explicitly about death, was made only to describe the light. What is that light? It’s intangible, conceptual, ethereal, pregnant with meaning. Everything is described except the thing itself.

There was an Inuit woman who was trying to explain something to western TV producers, and you know TV people, they’re waiting on a short cut. This woman described everything around the answer, and if you listened closely, and gathered up all these facts and thought about them, you’d be able to answer the question yourself. I can’t tell you the answer because you won’t learn anything. It won’t mean anything to you. People felt she didn’t answer the question, but I thought this was a great approach; describe everything around the idea, and then others can fill in the blanks.

The metaphor of light is overfreighted, so I’ve worked to make it more valenced. You, along with a number of other friends, the brotherhood who survived that time, understand this intrinsically through lived experience. I think of this new work as philosophical, while the earlier work is existential.

Now that I’m at the beginning of old age, the prospect of death has been the big “so what?” for so long, that while others are pondering mortality in a new way, our articulations are more sophisticated. We’ve lived through the possibility of death at a young age, amongst people who thought they were going to live forever. Youth generally behave as if they’re bulletproof, but even when we were young, we knew we weren’t. It’s not like we have more answers, but I think we have better questions.

![dan elstone 1[3]](http://mikehoolboom.com/thenewsite/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/dan-elstone-13.jpg)