1. Passionate ideas behind the flickering lights of film by Jon Davies (xtra, September 25, 2008)

2. Yes, Virginia, there is a Canadian cinema by Gail Singer (Globe and Mail, September 6, 2008)

3. Fringe Filmmakers Profiled by Randall King (Winnipeg Free Press, Feb, 2009)

4. A Practical Dreamer by Aaron Graham (Uptown Magazine, Feb. 19, 2009)

Passionate ideas behind the flickering lights of film by Jon Davies

(xtra, September 25, 2008)

Mike Hoolboom has established himself over the past three decades as not only one of Canada’s greatest film artists, but as one of the most passionate and hard-working proselytizers and chroniclers of what he calls the “fringe” film/video movement. In the 21st century, if we go by Hoolboom’s massive new tome of interviews with dozens of artists and filmmakers, Practical Dreamers: Conversations with Movie Artists, fringe movies can cover everything from independent and avant-garde cinema to video, installation art and projector performances — pretty much any moving images that can be appreciated as art. A follow-up to his Inside the Pleasure Dome, this collection is an indispensable resource for anyone who wants to understand how artists from Richard Fung and Steve Reinke to Daniel Barrow think about their work. It gives much more insight into the artistic process than any Q&A or pat artist statement could, so it goes a long way toward bridging artist and audience who, as Daniel Cockburn points out here, come to an artwork from two opposite sides: the maker sees the intent, the audience the result.

For Hoolboom making pictures humbly and as an individual — rather than as part of a machine like Hollywood — is a political act. He is a romantic and a true believer heavily invested in the medium’s potential for greatness. His questions often contain extensive, very smart and thoughtful insights into the work under discussion, though his highly lyrical and mannered writing style may rub some the wrong way (his references too can occasionally be obscure). His enthusiasm and his subjectivity, particularly his highly philosophical take on cinema and mortality, inflects every word, the direction of every conversation.

Each conversation is given at least 10 large pages; the interviews are more in-depth and considered compared to what one typically reads. Hoolboom cares deeply about the politics and aesthetics of movies, and he respects everyone here enough to really push them. That means that subjects like ethics or the value of making work that will likely be seen only by a handful of people come up often. For example when bad boy Jubal Brown goes on the warpath, Hoolboom is not afraid to challenge his apolitical nihilism (though they ultimately get stuck in a kind of moral communication breakdown). Hoolboom is always asking why, and for who rather than what, when, how. Second, the conversations occurred back and forth by email, often over a lengthy span of time, which means that both interviewer and artists could carefully labour over every word.

By choosing this route, Hoolboom sacrifices spontaneity for rigour — and by extension the book addresses a specialized audience. There’s nothing wrong with that, it’s almost as if he is refusing to sell a dazzling personality to you — which is what most journalistic interviews seem to be aiming for — suggesting that the work should do the dazzling first.

The most valuable conversations illuminate both the work and the personality behind it, particularly of those artists whose accomplishments are underrecognized. It was great reading about the trajectories of Midi Onodera’s or Ho Tam’s careers, for example, as well as finally seeing a substantial text about Aleesa Cohene’s work. In general the book is a particular treat for Torontonians as there are so many precious bits of local history and lore inside.

A few of the interviews sometimes read like cut-and-paste descriptions of the artists’ work that they took from grant applications. That’s why Emily Vey Duke’s section is so fantastic: of everyone here, hers is the most unashamedly, openly emotional, which tempers the volume’s analytic tone. She is unafraid to discuss the messy feelings that others choose to leave out. Donigan Cumming’s work is so raw, enigmatic and troubling — up-close and very personal documents of his friendships with desperate and damaged people — that it is heartening to learn of the searching, restless intellect and profound empathy of the man behind the videos. (He argues that his subjects’ failures simply “are more spectacular than ours.”)

Considering the current media environment it would have been interesting to hear more of Hoolboom’s thoughts on the current relatively easy access to not just production but exhibition too in the form of YouTube and other video sharing communities that reach millions of viewers. At one point he suggests that the “portals” of exhibition remain closed, which seems a bit dated — more interesting would be to ask how the internet has affected access, rather than proclaiming the situation still as dire as it used to be.

All in all, however, an involving and substantial read and an essential research tool.

Yes, Virginia, there is a Canadian cinema by Gail Singer

(Globe and Mail September 6, 2008)

Every generation has its own cinematic landscape of the imagination. Those large figures looming from the grand screen at the front of a movie theatre imprint on our minds all kinds of deceptions and delights. Over time, these accumulate, and a certain amount of our life view is nudged and streamlined according to what we have seen on those screens. (Not quite what happens when we watch movies on television screens at home, thank you, Marshall McLuhan.) What we Canadians saw until the 1960s and ’70s was almost exclusively made in America, invariably constructed around a classical Hollywood narrative template. Good guys won, bad guys lost. White guys were good, bad guys were a different colour. Women who let men have their way rarely married and settled down and had kids with them.

We made few distinctions, despite having preferences. We watched everything: horror pictures, westerns, screwball comedy and drama. Then, suddenly, another world opened up, at film societies, in little art houses or in language classes at universities: foreign films, with subtitles, unresolved situations, mysterious scrambled timelines, even no plots. Some moviegoers breathed a huge sigh of relief: Yes, there really was another portal through which to engage with the world. The consequence of this fusion of indiscriminate viewing was an opulent mental treasure chest of visual imagery, all located elsewhere, not here. Filmmakers play with these optical references, and audiences make links, consciously or unconsciously.

In Canada, in feature film, there are relatively few references to our own culture, which we (correctly) insist is significantly different from the U.S. experience. Most Canadians are completely unfamiliar with the thousands of films, good, bad and indifferent, that have been made right here, by those who live among us. Perhaps Canadian cinema can claim to be the least-seen movie product in the world. Too bad.

Everyone should read Mike Hoolboom’s Practical Dreamers: Conversations with Movie Artists and see the work of his more than two dozen moviemaking subjects. Hoolboom opens up a vast territory of investigation and playfulness about films that have the particularity to make us feel right at home. The task of seeing the films, like reading this book, takes a bit of work, but it’s worth it. The prerequisite is an open mind. (We can do that: Not long ago, no one would dream of eating raw fish, and look at us now.)

Hoolboom’s primer assists us in grasping the meaning of the work of some of the more obscure film artists working in our midst. His interview style is unmatchable: His introductory paragraphs are provocative and lucid. The writing reaches back in time and into Hoolboom’s own excellent work and filmmaking experience. He infuses with fleet phrases an aura of significance to his subject. (Where is his interview with himself?) By conducting the interviews on paper (or by e-mail), he elicits the wit and insight and the very thought processes of his subjects. This work is in the tradition of Godard and Truffaut and other filmmakers who became devoted to an examination of the work of their peers.

Hoolboom: “How do you see the ongoing disconnect between production and exhibition? Do you feel that most artists’ work simply shows to other artists, and that this in-crowd insularity is creating a body of work whose means and messages lie further and further from any who don’t already know the secret handshake, possess the decoder ring, speak the riddle?”

Montreal video artist Nelson Henricks responds: “I think there are ways for people who have no education in art or experimental film to enter my work. I have employed narrative and tropes derived from popular culture to facilitate this. I don’t think every artist needs to do this, but some of us do. This is a niche I am happy to inhabit because I adore pop culture. And art. I am a pop artist!”

Another, from Cree painter, performance/installation artist and film- and video-maker Kent Monkman: “Judeo-Christian understanding places the centre of the universe in the Middle East – that’s where attention always seems to be focused in the mainstream media. But if you don’t believe in that way of seeing the world, the centre of the universe lies elsewhere. … My work is about presenting another perspective … inserting lost (Aboriginal) narratives, the histories that have been obliterated and the absent mythologies.”

What one learns from Hoolboom’s investigation is that these are more artists than filmmakers. They paint or sculpt the screen with their images, and references to painting and sculpture are woven throughout the analysis of the work. This film art ought to be seen in the appropriate venue: art gallery or dedicated screening facility.

Toronto-based filmmaker Izabella Pruska-Oldenhof: “The general public has been fed the beautiful, clean image. They regard experimental cinema as beginners’ cinema produced by those who can’t make it in the commercial world. I doubt that … lovers of filmmaking in [U.S. experimental filmmaker Stan] Brakhage’s terms ever wanted their films to be placed next to commercially consumable blockbusters, far from it.”

Hoolboom, by expressing his love and empathy for the genre, through penetrating language and thoughtful interrogation, illuminates the work of these artists who dwell in peculiar obscurity, seen here and there by handfuls of admirers.

(An index would have been more than useful, an amazing game in which a reader examines the lacework of interconnection among not only the predecessors who inspired these artists but also the artists who cross-reference themselves by collaborating with each other.)

On the other hand, the much smaller Volume One of editor (and scholar) George Melnyk’s The Young, the Restless, and the Dead: Interviews with Canadian Filmmakers, is a much chattier, more conventional approach to the written exchange between questioner and interviewee. The responses from the filmmakers are more whimsical, less intellectual. You can read these interviews like magazine pieces. They are primarily Canadian feature film directors, and the interviewers are respected academics familiar with their subjects: Anne Wheeler, Guy Maddin, Gary Burns, the late Jean-Claude Lauzon and more.

I found Melnyk’s introduction particularly provocative in light of Hoolboom’s unapologetic literary approach: “an interview is very much of the moment … an interview done the next day, by a different interviewer … could result in something completely different.” Only Mike Hoolboom could have conducted the interviews in Practical Dreamers, whereas the questions posed and responses provided in The Young, the Restless and the Dead reflect little of the interviewers, and just a smidgen about the subjects. Nonetheless, as Melnyk comments: “I have launched this series of interviews with the hope that scholars and the public will have access to creators of cinema … whenever required.” Each of these books has a place in a film lover’s library.

Gail Singer is a Canadian filmmaker and writer currently studying drawing and painting and other fine arts.

Fringe Filmmakers Profiled by Randall King

(Winnipeg Free Press Feb. 2009)

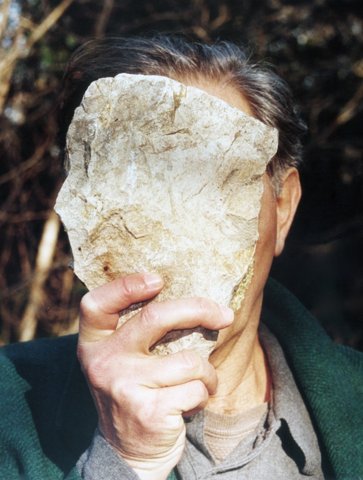

Experimental filmmakers are a breed apart. That, in a nutshell, is the thesis of writer Mike Hoolboom, an experimental filmmaker himself, in his book Practical Dreamers: Conversations with Movie Artists, which I being launched tonight with a talk by Hoolboom and screenings of four films by some of his subjects. Hoolboom says the filmmakers profiled tend to be shunted to the fringes of film art because their works are too different from conventional product.The Toronto-based Hoolboom offers an analogy: “It’s like if you spent your whole life buying chairs from IKEA, from a factory that makes a thousand chairs a week, and then one day you notice there’s a sound coming from your neighbour’s garage and you walk over and see they’re building this unusual thing. You don’t recognize at first what it might be, but eventually you see that it’s also a chair. But it feels and looks so different because it’s coming out his or her hands, and the way they’re living their life and it offers different kinds of comforts and different kinds of pleasures.”Carrying forth the neighbour analogy, Hoolboom profiles two local artists, Daniel Barrow and Jeffrey Erbach, among the 27 artists profiled in his book. He includes two of their films, Barrow’s Black Heart’s Desire and Erbach’s Under Chad Valley in the program of four films he’ll be screening.“Both are absolutely singular artists,” says Hoolboom. “Jeff looks like a feature film maker because of his work with large crews and his obsessive concerns about lighting and high-gloss cinematography. And yet his work emerges out of a wound,” Hoolboom says. “It’s about sharing a wound, and that sharing is more important than three-act structures, or driving towards some kind of narrative end.”Barrow, who frequently animates his works utilizing transparencies and an overhead projector, is also one of a kind,” Hoolboom says. Two other films screening tonight are Benny Nemerofsky’s Live to Tell – a cheeky performance piece cued on Madonna’s hit song, and Richard Fung’s Sea in the Blood, a personal doc utilizing the filmmaker’s old home movies. Copies of Hoolboom’s book will be available for sale.

A Practical Dreamer by Aaron Graham

(Uptown Magazine, Feb. 19, 2009)

Prolific Canadian author and experimental director Mike Hoolboom, whose numerous retrospectives have screened everywhere from Switzerland to the Czech Republic, will unleash his new book, Practical Dreamers: Conversations with Movie Artists, at Cinematheque on Feb. 20.

On the following evening, Hoolboom will introduce two of his favourite Canadian films – both rarely screened – as part of an ongoing series entitled Cinema Lounge.

Practical Dreamers sets its sights on underpublicized Canadian fringe media artists, from Winnipeg’s own Jeff Erbach to Kent Monkman, Daniel Barrow, Donigan Cumming, Steve Reinke and Peter Mettler. Twenty-seven artists in all, Hoolboom, who chose the title after reading an inspired quote from the estimable jack-of-all-arts Man Ray (“The streets are full of admirable craftsman, but so few practical dreamers”), engages all of the creators in one-on-one conversations about what led them down the filmmaking path, and the particulars of committing their idiosyncratic visions to film or video.

Copies of the book will be sold in the lobby and, to supplement the presentation, Hoolboom will screen four short films by directors featured in his book.

Under Chad Valley, directed by Erbach in 1998, is a particularly grisly yet arresting vision about silent butchers, while Black Heart’s Desire, directed by Daniel Barrow in 1995, is an erratic, incisive animated work that captures how Barrow’s illustrated-challenged friends envision him. Rounding out the program are Benny Nemerofsky Ramsay’s Live to Tell (2002) and Richard Fung’s Sea in the Blood (2001), both of which I’ve yet to see.

On Feb. 21, Hoolboom presents View from the Other Side of the Falls (John Price, 2006), a seven-minute short from Toronto that dabbles with the very chemical properties of film, and Up to the South (Jayce Salloum + Wallid Ra’ad, 1992), a 60-minute doc on how the Israeli-Palestinian conflict caused an occupation and resistance in South Lebanon in 1978 and again in 1992.

While the latter sounds slightly more accessible than the other five shorts, don’t let that scare you: all are worth checking out.

In an intriguing essay entitled ‘My Best Friend is Not a Documentary’ on Hoolboom’s website (www.mikehoolboom.com), the writer classifies fiction and documentary directors as tops and bottoms. Fiction is “for tops,” as it “commands and dictates,” while the documentary director “learns to accept the world as it already is,” in effect, bending over. With both programs over two nights, we couldn’t have better examples of what exactly Hoolboom means.