Beyond the Usual Limits: an interview with Deirdre Logue

Movies have been designed from the very beginning to promote the beauty spots of our lives, the high impact thrill of a face. But there is another kind of beauty which is unafraid to lose the mask of youth. It is the beauty of witness, of a person who has returned from the frontier. What a gift this is, to be able to look into a face which has seen too much. This is our passkey to the labyrinth, to be granted admission to the very brink of what can be seen or imagined. This face, this look, carries it all, if we could learn to read it. These faces are a testament: I was there and didn’t look away. I saw what it was. And now I give you the gift of this face which has looked. The artist performs in each of her movies. This work is too important to be left to others. She never leaves the stage of the frame, and hardly speaks, she lets her body do the talking. She shows, demonstrating the cost of living in a body. She offers us the trial of ideas and their execution, her skin appearing as a book, written over and over, and without end.

Emily Vey Duke and Cooper Battersby.pdf

I Am a Conjuror: an interview with Emily Vey Duke and Cooper Battersby

Is there nothing they won’t say in front of one another? Is there no terrible infatuation, no secret longing that they cannot share, instantly, as soon as it occurs to either one of them? The foundational vaults of repression that are at the very root of togetherness have been left behind by this dynamic duo whose ongoing domestic adventures provide a glimpse of what couples might look like in the next century. While they wait for the rest of us to catch up they keep busy taking their funny, damaged, wordsmart incarnations out for a walk in video after video. Being Fucked Up(2000), for instance, opens with our heroine huffing crack, singing a song about a perfect nature world, before a cartoon drawing says via voice balloon, “Her soft breast. The sweet, warm milk. Her arms around me. I will punish her for making me wait!” More songs and drawings follow before it concludes with a series of questions which they answer by violently shaking their heads yes or no. Do we need to know more? These bitter sweet episodic tapes might be the latest pop epistle from a shoegazer outfit from Portland, deadpanning their way through another MTV day about getting through their 20s one habit at a time. Instead they have turned to the sometimes rarefied zone of video art and laid their claim, recasting themselves as backwards talking scientists lounging in the bath.

Ironic Nostalgia: an interview with Nelson Henricks

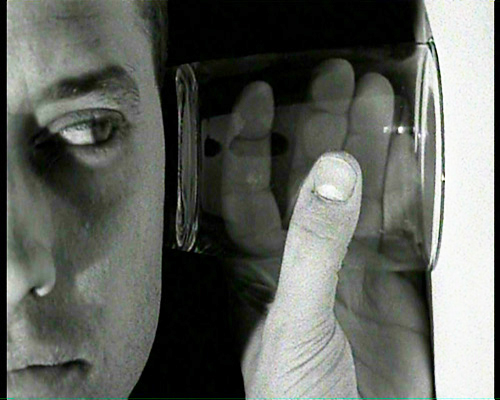

There is something old and sad and wise in his expression, and then he bounds up from the chair and squeezes out another bon mot on his way to the fridge and I have to pinch myself in reminder that he is still young. In his face which erupts in sudden and unexpected delights I can feel some deep acceptance of limits, it is a face which has glimpsed its own frontier, it has combed the furthest reaches of itself before settling into a more comfortable posture. But the gravity of his speaking carries this understanding of limits, and it is a knowledge that he brings into one videotape after another, though in truth he is a kind of filmmaker in disguise, with his careful framing and his raw to the skin feeling for the surface of pictures. He was inclined from the beginning towards the cinema but played out his aspirations in the low cost realm of video, at a time when extreme technical limitations led many to an artless style. But he has been steadfast in his pursuit of beauty, the compulsions and lists, the mad detours and taxonomies, they would still be fine and sharp and well cared for if they were beautiful, wouldn’t they? Yes they would. Nelson is a prairie boy living in Montreal, a single-channel maestro locked up in galleries, queer eyed in a straight world. These displacements, enacted with a painstaking precision and meticulous attention to detail, continue to mark his work.

There are some painters who rush out into the landscape and settle their tools in front of a tree or a mountain or a running body of water. Nelson is not amongst their number. He is a studio artist. He is busy building models, he is out in the world and then he takes that experience back into the studio and changes its scale. He blows it up so large that we have to walk around it and let it slowly enter us, or else he reduces it in scale, shrinks a terrible tragedy down to a few enigmatic images, caught in a series of variations, until the heartbreak becomes clear enough. He builds models for living and seeing and thinking and then sets them loose, imagining that the audience will be as intelligent as his makings. Yes, after all that, he believes in utopia after all.

Thinking Pictures: an interview with Richard Fung

When he tells me the story of how he got his start in fringe media I have to sit back in my chair for a moment. Wait, wait. There was a time when Richard wasn’t making videos? It’s hard for me to grasp exactly, just as it’s hard to imagine what the Canadian media art scene would look like if it had not grown up with Richard’s accompanying text missiles which have blown apart commonly held wisdoms again and again. His justly anthologized Looking for My Penis: The Eroticized Asian in Gay Video Porn took on stereotypes of gay desire. His Programming the Public missive looks at the way queer fests help shape the identity of its audience (who is looking in the mirror now?) It begins with this line: “Whenever I go to a gay bathhouse, I’m struck by the ordinariness of so many of the men, who seem to evade all recognizable gay styles of masculinity and femininity…” One thing is for sure: Richard always knows how to lead, though his characteristic modesty keeps him from standing at the front of the theatre and hectoring us with his keen intelligence. For twenty years he has reworked the documentary, leavening it with personal insights, his camera inside the home, settling it beside his mother, then his father, and most memorably, his sister Nan. In his brilliant summary work Sea in the Blood (2000) he lays down a duet of his sister’s fatal illness and his own lifelong romance with Tim, an AIDS activist with an illness of his own to contend with. The personal is always and necessarily political in these mosaic recountings which never shirk from the task of unsettling received wisdoms. How warming to imagine that we live in a post-identity culture, that we’re all just getting along, that the glass ceilings and racial profilings and hate crimes are relics of a bygone time. And how much rarer, and how much more urgent, is the need to continue to point out the inequities which continue to exist in a North American art world which is primarily white (from consumers to producers), and where power brokers in the off off off off Broadway world of fringe productions are still similarly monochrome. Richard’s work (as teacher, mentor, programmer, artist, writer) stands in the face of this backwards tide, quietly persistent, bristling with intelligence, raveling out the effects of global empires in local details.

Home is a movie: an interview with John Price

He looks like someone who is always getting off a horse or exiting a scuffed motor car with the scenery whispering behind him in delight, he has that rugged kind of handsome about him that makes you trust him with things, maybe there’s a leak that needs fixing in your life, maybe those thoughts never had a roof at all and it’s time to call and ask him to come down and have a look.

He belongs in a kingdom of geeks, all bent to a narrow geek task, in his case it isn’t golfing shoes or birding or obscure jazz dates that winds him up, no, he loves the machines of cinema. He shows me this little wooden box with a handle, oh man it’s a 35mm camera, not unlike the ones that got it all started at the turn of the last century. He has to crank the film through by hand, and he can’t look through the lens to see what the camera sees, instead he has to feel his subject, it’s not a point and shoot type situation, he has to take a stand and put it up on three legs and start winding. When it’s done he likes to invite friends over and show these large gauge manufactures in his living room. I’m full of barbeque and conversation and the projector sounds like a space ship starting up and now there are pictures, no larger than the size of this piece of paper, projected against John’s living room wall. Kids rush in and out of the light and together we make the soundtrack.

His pictures are gathered between births, after buying ice cream for the kids, before going out into the neighborhood with his boy and seeing everything for the first time again. He can’t spend long months in the edit room anymore, watching the pictures slowly dry out and separate and come back together again, poring over past moments to see what secret codes might be unwrapped so that they can speak to each other. Paternity has ushered in a new body of work which refuses an engineered escape, a release from the too many pressures. The all hands presence required by his children has passed into his shooting, his hand processing, his selection of stocks and assembly of rolls. Second guesses are behind him, there is no forever and ever or once upon a times, only now. He is filled with eternity and shares it when he can, admitting it into his little crank box of a camera and then pouring it out again. When it’s time to show things they come straight from the camera, or else are blown up in patterns of recognition and then he splices the rolls together, and if it gets scratched or ruined on its way through projectors then it will wear the scar or surrender to destruction. There’s no time to look back and he wouldn’t have it any other way. He’s ready.