Scrapbook by Adi Chesson

A Refuge in which Film Can Be Reinvented: Film Festival Marseille Part 2 by Henrike Meyer

Scrapbook by Adi Chesson

(Format Court Magazine (formatcourt.com), May 13, 2016)

“I couldn’t tell if emotions were somewhere in my body or a place in the city.”

Realized over a period of 50 years, Scrapbook (discovered at the IndieLisboa festival in the “Silvestre” section) is a documentary about the residents of a home for the mentally challenged. Narrated and commented upon by one of its patients, Donna Washington, the film reflects on the conditions of treatment and detention in America during the sixties.

Mike Hoolboom is a director sensitive to the question of difference, to those who continue to live and work in the margins. He is now emerging as one of the most innovative filmmakers from Canada, a country which has also produced talents like Guy Maddin, or a younger generation represented by Félix Dufour-Laperrière or Theodore Ushev.

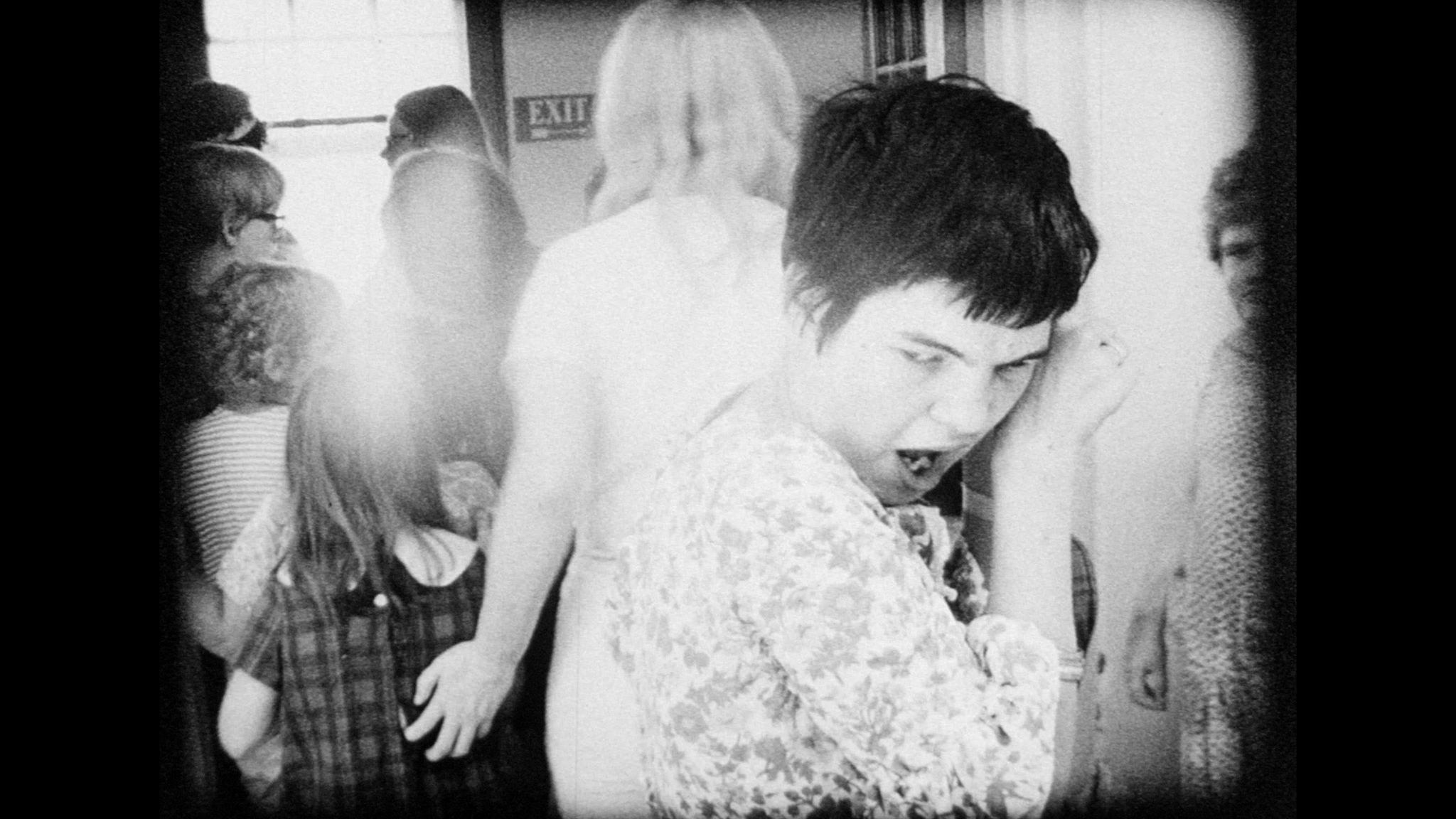

Guided by images shot by the artist Jeffrey Paull in Ohio’s Broadview Developmental Center in 1966, Hoolboom revisits scenes of the asylum for children with autism. Paull’s work at the Centre was intended to grant patients the opportunity to actively participate in the creation of portraits, to develop (both in and out of the darkroom), a series of views, a subjectivity grounded in pictures. As opposed to the delirious proximity of autism, pictures might grant the distance necessary to compose a self, a line between self and other.

Donna Washington’s sometimes disjointed speech focuses on the feelings and fragilities of patients facing the frank stare of the camera. Through the voice of an actress (she considered her “more real” for the film), Donna evokes with great immediacy the difficulties experienced by her and her colleagues to absorb, express and manage emotions. Sometimes speaking of herself in the third person, the text attests to the complex and ambiguous identification of patients whose identities might be found and lost in the faces of each other.

The pictures are the singular work of Jeffrey Paull, who manages to recompose the shell of identity in a series of camera encounters. Half a century later, Hoolboom brings one of its subjects back into these frames, creating a loop that admits another view of these lived moments.

Donna evokes this dilation of time several times by browsing through this motion-picture album filmed in her youth (the movie’s pictures are the “scrapbook” of the film’s title). These compressions find their echo in a weighted soundtrack composed by Stephan Mathieu. The track operates a distressing counterpoint between sound and image, its ambient sounds opaque and mysterious, its obstinately dissonant tones suggesting the fear that underlies centres like this, before the advent of community-based health care.

Scrapbook necessitates both comparison and contrast with Frederick Wiseman’s infamous Titicut Follies (1967), shot just a year later. This highly controversial documentary proceeds via cinema verité treatments of the patient-inmates in the Bridgewater State Hospital for the criminally insane. There is more than information on display here, as it mercilessly unveils the abuse so widespread in institutions like this. But Hoolboom and Paull are far from putting the cinema audience into a jury dock, weighing the actions of a system given shape by an architecture and administration. Their goal instead is to grant agency to one of those who can voice her own experience, five decades later.

A Refuge in which Film Can Be Reinvented: Film Festival Marseille Part 2 by Henrike Meyer (Dasfilter.com, August 12, 2016)

…The last movie I saw in Marseille moved me the most. In Mike Hoolboom’s Scrapbook I had time enough to feel what it means to look into a camera, to make a picture, and to produce pictures that think. Formally, this 18-minute film offers a minimum of procedures: black and white 16mm film material, intertitles explaining the origins of the pictures, an abstract sound score and accompanying voice-over. The way these elements are arranged, their relationships with each other, what and how they signify is immensely impressive. The film allows us access to a world that is otherwise closed. Even days after the festival the film is still alive in memory.

The film material was made by Hoolboom’s friend Jeffrey Paull in 1966, during a film workshop in a facility for autistic children and young people in the USA. The participants took pictures of each other and of themselves, and learned to process film “in order to re-see themselves,” as the voice-over suggests. Many found the experience therapeutic.

One day Paull brought his Bolex movie camera and began shooting what would eventually turn out to be 30 minutes of material. He produced intensely intimate portraits of children and young people. They look into the camera, smile and make faces.

Here the everyday becomes visible again: one caregiver sits with a child on her lap. He rubs cheeks with her on one side, and then another. A child eats a cake and seems blessed. Near the beginning of the film, a girl with glasses smiles into the camera. “Oh, it’s you,” we hear in voice-over. Fifty years after the recordings were made, Hoolboom searched the internet for participants from that time. Donna Washington answered the call and was ready to engage with her past selves. Her responses were recorded, and then edited to create a kind of script that we hear in voice-over, spoken by an actress.

Donna’s words are already poetry. She speaks about the girl wearing glasses that we see early in the movie in a way that challenges classical notions of perception and self-image. The “I” is not a closed shape. The boundaries between self and other (whether another person, or a drape, a bench, sunlight) are fluid and permeable. Environmental impressions are vivid and lively. You could become a colour, subjectivity can be projected as easily into things, contact moments, another’s face. What is sometimes experienced in shamanistic rituals was for some of these young charges, a permanent state. Through their encounters with a camera and their talks with Jeffrey Paull new possibilities emerged. Working with pictures she had made herself, Donna relearns the act of naming, uncovering pictures that she begins to identify as “I.” It is very touching as she says at the end that they have lost the fear of other’s faces since they can also see pieces of themselves in them.

The language is precise and denotative, and at the same time open-ended. Filled with the beauty and humour of truth. This encounter with pictures from another world provokes statements about cinema and what unites us as humans. At the end of course the question remains – how can you see these films? Not likely in movie theatres, which is a shame! They buzz in a festival cosmos, it’s good that places like Marseille still exist. They are hideaways in which film can be reinvented.