Scrapbook: an interview with Mo Gourmelon (May 2016)

Mo is the director of La Saison Video, an online portal (http://www.saisonvideo.com) that pairs movies that are temporarily on view. In late 2016 Scrapbook (18 minutes 2015) will be paired with Watch My Back (part one) (10 minutes 2010) by Jorge Lozano.

Mo Gourmelon: What was the starting point of your movie Scrapbook? How have you returned to these images 40 years after they have been made, and how did you make selections from these images of Jeffrey Paull’s?

Mike Hoolboom: Some pictures can take a long time to see. It’s hard to feel that today, when pictures arrive in our cameras before we can see them. But some images only come into focus after many years. Some instants in our lives can be so crushing that the turn to face them can last an entire lifetime.

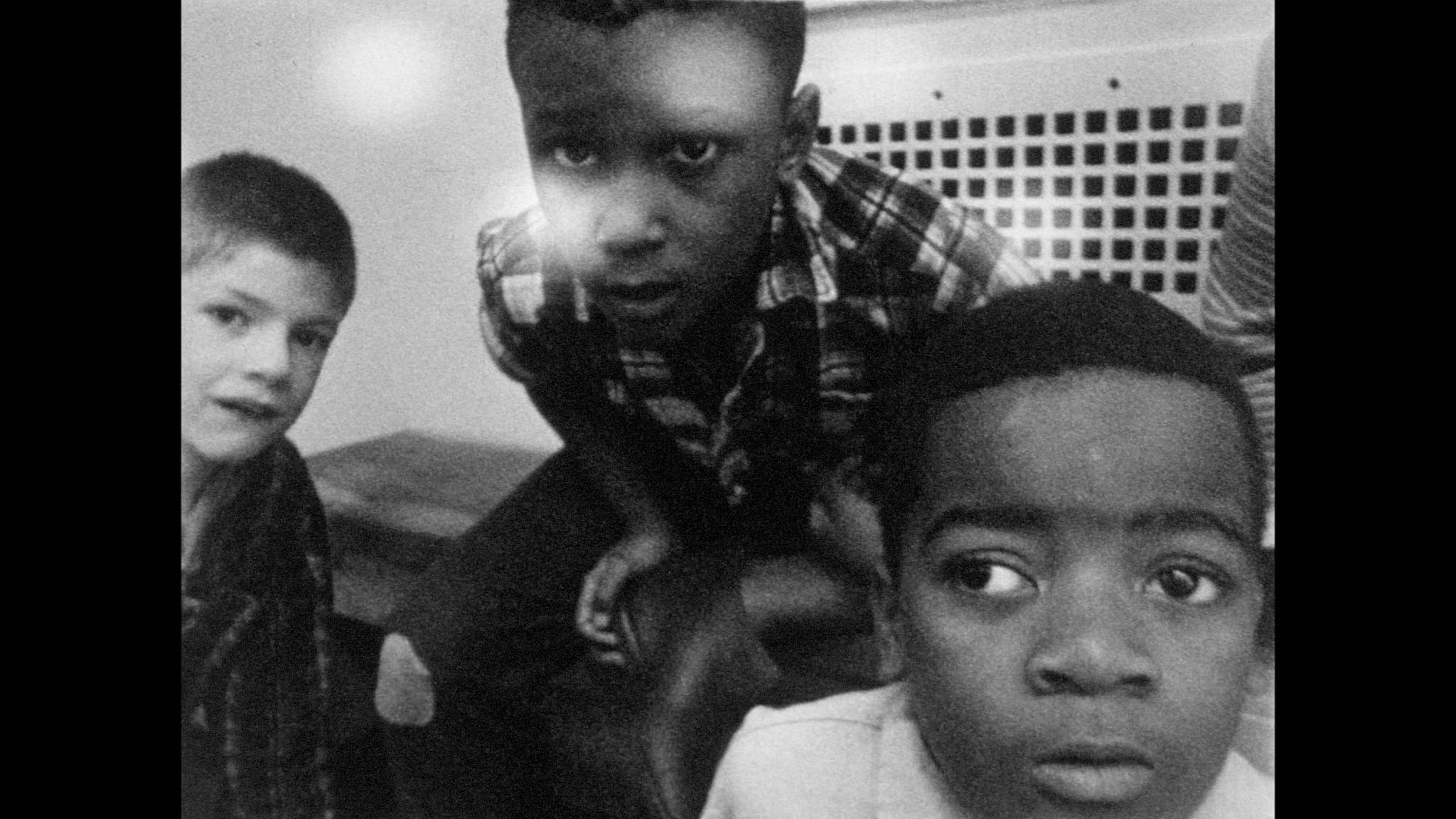

The images in Scrapbook were made in 1967 in the Broadview Developmental Centre in Ohio. It was a live-in joint for mostly kids who had some kind of mental challenge. My friend Jeffrey Paull was hired fresh out of Boston University as a kind of audio-visual healer. He was tasked with setting up a darkroom (chemistry, mixing trays – no instant snapshots were possible at that moment), and teaching the kids how to shoot photographs, develop the film and make prints. They spent most of their lives on the grounds, so their subjects became, almost inevitably, one another. In another words, it was a project of group portraiture. While Jeffrey was there, he made some 16mm footage, not much as it turns out, less than half an hour altogether, ten rolls of 16mm shot with a wind-up Bolex camera. I used most of this footage, though none of the colour (he shot two rolls of colour) that was made outside, and has a different feeling tone.

Jeffrey was one of my media profs at Sheridan College, which I attended in the early 1980s. He was the second person I had ever met who saw the world as an artist, as an unfolding set of questions and uncoverings. I went to college knowing that I wanted to make movies, but it wasn’t until I drifted to the nascent film co-op around the corner from where I lived that I finally saw the kinds of things that were urgently compelling. That place was called the Funnel, and it featured a hundred seat theatre built by the membership, along with modest production gear, and a collection of work available for distribution. Like the old Hollywood studios, it was a vertically integrated enterprise of production, distribution and exhibition. They ran two screenings most weeks, and guests arrived from around the world. I couldn’t tell what was happening most of the time, why these strange forms appeared, even what most of the work was about, but none of that seemed troubling. It was part of an anti-capitalist front, and that was seemed more than enough.

Mo: Did you meet Donna Washington, one of the patients of the psychiatric hospital? She remembers and testifies, although in the end she says that she prefers that you use an actress’s voice instead of her own.

Mike: Jeffrey gave me the footage he had made in Ohio ten years ago, and I watched it and marvelled and then put it away. It needed more time. Then I thought I should try to find someone who was in the original footage. The internet is very helpful for these searches. I found Donna through an online ad, and she was interested in seeing herself from those many long years ago. I sent her the footage, and we arranged a time where she would see it for the first time, and comment on it while she watched. I also asked her a lot of questions. I was particularly interested in her relationship with the camera, with the project of portraiture as it relates to her own autism, and her memories of Jeffrey. She was extraordinarily articulate, she had done years of therapy, and had given voice to her journey many times. Her observations around perception are so vivid and strong. The way she could identify with, even become, a chair or a drape or a colour. Her ability to articulate her very particular emotional responses continues to feel like a gift.

Mo: The first time I saw Scrapbook screened, I was really impressed by Donna Washington’s comments, their clearness in contrast with the images of children and teenager’s bodies. Comments such as: “I didn’t have a body yet. That came later.” Then: “Jeffrey taught me a lot about how to see a face. How to, receive a face. What Jeff showed me with his camera is that you don’t have to get stuck in someone else’s face.” There is a gap between these existential declarations and generally accepted ideas about autism.

Mike: Autism is a word that describes a pretty wide range of conditions, language can be such a blunt instrument. It’s true though that we never hear any of the onscreen kids speak in sync sound, there are pictures but not sounds, what the movie makes possible is a time travel that brings a faraway adult voice back into these small bodies. She marks and remarks on them. I believe, though I can’t know this for sure, that many of the sentences Donna offered up had been spoken before. She is still performing a version of herself, like we all do. Her long journey from a feeling world that was often overwhelming, and where the boundaries of the self were troubled and uncertain, to a place where she can stand and speak from her own subject position, is a passage that feels lined with words, descriptions of her past and future state. Though each of her sentences has roots in the body, she isn’t talking about theories or ideas about experience, somehow the words are an integral part of the experiences that they are describing. She has had to recreate a home in language, even as she has had to reimagine her body as her own. How do you receive a face when you can’t tell for sure where your face begins and ends? As Donna so eloquently describes, it was by coming to terms with the face of someone else, that she was able to identify and reclaim a face that she could call her own.

Mo: You say in your film that we hear a “faraway adult voice (put) back into these small bodies.” Is this the reason why you chose Watch my back part one, Jorge Lozano’s film, to be shown with Scrapbook? In Jorge’s movie we don’t see disturbed faces, only a back, there is no sound and the subtitles take place of the voice-over. The past is coming back to understand the present.

Mike: I think Jorge’s movie is one of the most important ever made in Canada. It offers us a subject and subjectivity that is rarely shown in fringe media, an immigrant underclass (Fred Moten prefers the term undercommons). With great sensitivity, the artist protects the face, even the voice, of his subject, so he has his charge facing away from the camera. We are offered his back, even as he no doubt is offered the backs of many white people he has encountered here in the multi-cultural fantasia of Toronto. While the gang violence he describes with such intimacy is far removed from Donna’s experiences, in both instances we are able to gain entry into a marginalized person’s experience. And both of these people speak to us, very directly, with great articulation and energy. In both cases, language is a marker of belonging and power, an entry portal into a world that refused them both, for very different reasons, so they had to develop an outsider’s speech.

Scrapbook: an interview with Vincent Poli (June 2016)

Originally published in: (FIDMarseille Daily)

Vincent: How did you arrive at the idea of re-using images 40 years after they had been made? Did you have to go through a lot of Jeffrey Paull’s images while making the selections for your film?

Mike: Shortly after he graduated from Boston University’s thrilling film program in the 60s, my friend Jeffrey was hired by the Broadview Developmental Centre in Ohio to set up a darkroom, and work with the kids there, help them take portraits and learn how to use cameras. It was a utopian moment for the new field of media studies, everything from feminism to animal rights might be reimagined using portable imaging technologies that would allow even the most marginalized voices to author their own expressions. Jeffrey shot half an hour of film there, and the footage sat for many years until he gave it to me. I also let it sit for a few more years, wondering what to do with this gift. Wasn’t it Lacan who said: love means giving something you don’t have, to someone who doesn’t want it? Sometimes it can take a long time to see an image. That’s what I think both of us were waiting for, we needed to find some way to make these long ago pictures present again, to make them visible.

Vincent: Donna Washington used to be a patient in an institute for mentally challenged kids. How did you meet her?

Mike: We met online, like so many do these days. How else to find folks outside of our usual patterned grooves? She is shown in Jeffrey’s footage scribbling out the film’s title.

Vincent: Donna Washington thoughts are surprisingly constructed. Could you tell us more about this?

Mike: Donna is autistic, she experienced feelings (good or bad) as overwhelming in intensity. She struggled for many years to be able to separate her identity from the furniture, or a drape, or someone else. The experiences she describes are very close to those narrated by religious mystics who recount a flow of interdependence, a shattering of boundaries. But the mystics didn’t live in this state permanently. Donna struggled for many years to draw a border around herself, and one of the ways she did that was through language. She has described her journey and her experiences many times, in a variety of settings, clinical and otherwise, so perhaps it’s no surprise that she is so articulate in the movie’s voice-over.

Vincent: Finally, it seems to me that Scrapbook (18 minutes 2015), by delivering different faces to those mentally challenged kids, is in line with your films dealing with HIV — fighting other people’s looks, going beyond biased ideas. Do you agree?

Mike: Yes, this movie tries to give voice to someone who is too little heard. My movies around AIDS (Frank’s Cock, Safety Film Collection, Buffalo Death Mask) similarly try to voice an experience that is commonplace for millions round the world, yet the media swaps out personal experience for numbers, science talk and fear. The voice of fear is too often the voice of the authority, the surrogate parent, the president, telling us what is no longer possible, about why we have to stay small and separate. Perhaps these movies are a way of turning certainties into questions again. What would it be like to meet each other without fear?

One of the biggest questions for those who have been delivered to the scientific miracle of the HIV cocktail resurrection is: how do you live twice? How do you invent your second life? This is further explored in a recent book co-authored with trans artist/activist Chase Joynt You Only Live Twice (2016) (http://www.chbooks.com/catalogue/you-only-live-twice). Part of the role of fringe movies is to narrate different lives differently. Form and content can’t be separated.

Scrapbook: an interview with Adrian Martin (2014)

Adrian: Your new film, Scrapbook, is especially haunting. In part, it involves the intimacy between a cinematographer, your friend Jeffrey Paull, and a young woman living in a mental health institution, Donna Washington – who is given a chance, many years later, to see the footage taken by Paull and comment on it (her words were transcribed and then performed for your soundtrack). There is a hallucinatory edge to this piece – a dive into the instability and uncertainty of personal identity. But also, would you say, a specific social context?

Mike: Donna’s an older woman now, she was just a girl when the pictures were made – so her reactions to seeing herself again after all these years were really striking. “Oh, it’s you,” she says, as if greeting a long lost friend. Or one that had been left behind, almost forgotten. One of the questions I had coming into the project was about the relations between staff and residents. Many residential centres existed in the United States, it’s less common now. Too often after one of them closed, stories emerged about patient abuse, there was one breaking scandal after another. In an environment with so little outside scrutiny, it’s not hard to imagine why. But those stories never stuck to the Broadview Developmental Centre in Ohio. The footage on view here is just a fragment of what went on there, but it shows a staff that is mostly young black women. This was in the 60s, at the height of the civil rights movement, when Black Power was a rising tide. The footage shows a very mixed group of kids, it’s an integration that remains unusual in America. Of course this is a private space, and for the most part undocumented and unseen, these are unwanted children, so special conditions can exist here. It’s as if you need to be considered crazy to be integrated in the US.

There are several instances where we can see interactions between the caregivers and the kids, and I think these are performed with great tenderness and care. There is one beautiful scene that Jeffrey films so well. He shoots down a hallway, and in the open door we see a young boy rubbing his cheek up against the cheek of the caregiver. Jeffrey grants them this distance, this space where they can be with one another, we look on from a distance. He is filming with a Bolex, which is a relatively large wind-up camera that makes quite a sound when it’s running and the spring is being released. In between each shot you have to wind it back up, so filming is never a secret, everyone knows where he is and when the camera is rolling. So he begins by filming discreetly down the hallway, and then he moves across the axis, he passes them, and in that passing one might imagine there is a mutual acknowledgment and consent. The second shot in the sequence brings us a closer view from the other side. It’s a little embarrassing to see this closeness. I can see two things in her face. She’s warm and close and smiling, but she’s saying (without words): not now, the camera is rolling, let’s not do our thing right now. But also it’s clear that the boy doesn’t care about the camera, he needs this contact, this intimacy, this touch, and she responds to that need, the hope of this boy is stronger than her embarrassment, and that says so much about the quality of care that exists in this place. Don’t you think? Her face says no and yes, and then: how can we create a space of attention for each other? Or even: how can you live as a child without parents?

Some of the kids look, at least temporarily, absorbed in alternate states. They’re folded up in chairs, or staring at the walls. Donna describes the act of seeing as an act of becoming – she doesn’t see the yellow drape, she is the yellow drape. It’s sublime and terrifying. What she narrates in the film is a slow and difficult process of separation from her sensory contact points – she learns to divide what she sees, touches or smells from herself. This separation allows her to become intimate. Though it happened in stages. She talks about a strange and terrifying period with Kim, the person who she identified as herself, only she was someone else. Donna constructed a self, or even a series of selves, out of pictures. She talks about watching television, or watching how the others behaved, and then building a self bit by bit. Don’t we all do that, to some degree? Donna shows us how hard we’re all working to “get along,” and de-naturalizes what we too often take for granted.

Jeffrey worked there every day so he’s more than familiar with each of them. He’s often shooting with a 10mm lens, their faces inches away from the lens. The pictures offer an immersion into another world. What Donna offers through her narrations was a way inside these pictures, I hoped that language would defeat any sense of spectacle or freak show. Instead the voice demonstrates a deeply internalized sense of how this world operates, and invites the viewer to enter these rooms on their own terms.

Adrian: Do you use the original footage “as is” – basically just juxtaposing it with the voice recording – or did you manipulate and structure it a lot?

Mike: I tried to create a series of scenes with the footage, leading up to a dazzle of light in the cafeteria where everyone is leaving or melting. The cafeteria is the final setting, once they leave, it’s over. But there wasn’t so much footage to begin with, and it was all rendered with such tenderness that it was hard to remove their faces, their hands, their gestures. There was an undeniable energy in the original footage that had to be respected, the energy of these encounters, this seeing. That was the map. Donna’s words became a way to read that map.