Panic Bodies 70 minutes,16 mm, 1998

“A meditation on the after-life that’s as powerful as anything in cinema …one of the truly defining movies in Canadian filmmaking history.” (Peter Goddard, Toronto Star)

“We have come to expect only the dazzling and uncommon from the prolific, prodigiously talented, and frequently transgressive Mike Hoolboom, perhaps the most important Canadian experimental filmmaker of his generation, and the startlingly beautiful Panic Bodies delivers the potent goods. Like much of Hoolboom’s gorgeous, unsettling recent work, Panic Bodies is infused with an AIDS-era horror at the body under siege, with a palpable sense of wonder and revulsion at our flesh-and-blood corporeality, at ‘being a stranger in your own skin.’ The film’s multi-levelled meditation on morality moves from rage to reverie, and unfolds in six often-hallucinatory episodes: Positiv, a multi-screen monologue about AIDS; A Boy’s Life, a masturbatory revel; Eternity, a reflection on Disneyland and death, 1+1+1 a devilish, pixillated black comedy; Moucle’s Island, a nostalgic lesbian idyll; and the concluding, elegiac Passing On.” Jim Sinclair, Pacific Cinematheque

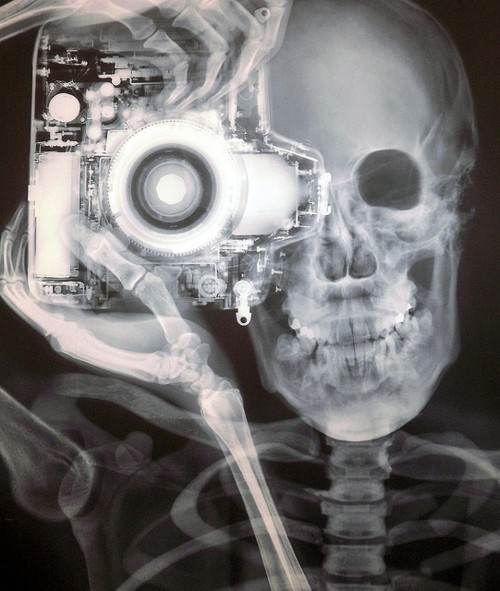

“Filmed in the shadow of AIDS, Panic Bodies is Hoolboom’s testament to the permanent impermanence of the flesh. The film’s six parts show the range of Hoolboom’s engagement with mortality, from rage to reverie… Whether he’s remixing Terminator 2 or concocting a female paradise, Hoolboom finds a balance between razor-sharp intellect and palpable love for images and sounds. To watch Panic Bodies is to see what it means to live and die in the cinema.” Cameron Bailey, NOW

“Often challenging, always mesmerizing, Panic Bodies is an intensely moving meditation on post-AIDS mortality, from one of Canada’s leading exponents of fringe film. Structured in six self-contained segments, ranging in tone from rage to reverie, Hoolboom confronts his own HIV+ status, the impermanence of the human body and the frailty of human existence. An eclectic ensemble piece, Panic Bodies draws its inspiration from a number of sources: science-fiction old and new, found footage and home movies as well as collaborations with Ed Johnson, Tom Chomont and Moucle Blackout. Wildly playing with genre and gender, Hoolboom’s film combines masturbatory ‘monodrama’ and pixilated slapstick, lesbian idylls and memento mori in a virtuoso feat of technical skill and cinematic imagination.” London Lesbian and Gay Festival

“Paul Ricoeur said the two toughest things humans have to face are that we will die and not everyone loves us. Panic Bodies catalogues earthly attachments-physical, material-as part of the spiritual process of acknowledging mortality, of preparing to die.” Steve Reinke

“Panic Bodies is Mike Hoolboom’s new feature-length experimental film in which he confronts and displays his own battle with AIDS and explores the body’s various transformations in sickness and in cinema. One of Canada’s most important filmmakers and art activists, Hoolboom (who collaborated on Matthias Mueller’s Pensao Globo) mixes visual poetry and personal confession with visceral, transgressive explorations of the human body.” San Francisco Cinematheque, Winter 1999

“Canadian experimentalist Mike Hoolboom is less ‘persistent’ than Van der Keuken by about twenty years, but his career is also full of treasures. Among these is Panic Bodies (1988), a six-party study of the beauty of the body and its tragic temporality. Hoolboom has turned his own experience as an HIV-positive man into art, drawing on such disparate elements as home movies, microscopy, found footage from a 1930s ‘naturist’ film, and a whimsical miniature melodrama about a man in search of his lost penis. In a voice-over to the last segment, Hoolboom talks about the ‘conspiracy of chromosomes’ that make up the human being, but the phrase is ironic; for him, nothing is more human or felt than what that conspiracy has created.” Gary Morris, SF Weekly, April 21-27 1999

“Panic Bodies is an astoundingly beautiful cavalcade of images that explores the ephemeral nature of life as seen through the eyes of a filmmaker with AIDS; it is also a paean to the body as a site of sexual pleasure and beauty, one that ultimately betrays the filmmaker. The narrator remarks that before learning he was positive, ‘life had a unity of design, and that shape was my body.’ The six parts of this elegant film are heartbreaking in their relentless celebration of daily life. The first section, Positiv, unfolds with icons of childhood, doctors and old wrestling films; the simple act of telling seems to foster the accretion of memory. Eternity takes the form of a letter about fighting disease and practicing loss, superimposed over haunting images of old teacups, people in boats and water. Moucle’s Island is a lovely reverie of naked woman on a beach playing ball and leapfrogging. Passing On mines memories of siblings, parents and an estranged aunt who whispers presciently to the filmmaker at age sixteen, ‘Never grow old.'” San Francisco International Festival, 1999

“Using studiously chosen dreamlike images, Mike Hoolbooom’s six-part experimental feature examines the body. One of Canada’s pre-eminent avant-garde filmmakers and a master in the art of found footage, Hoolboom draws compelling images from many sources, including films, music videos, home movies, scientific filmstrips, as well as his own newly shot footage. The six chapters of the film all work together to evoke dreams, memories and the stark reality of bodily experience. Even at his most abstract, Hoolboom has complete command over the form. His montage of sound and image convey notions of morality and impermanence in a continually inventive and eye-opening manner. Panic Bodies is experimental filmmaking at its finest-stunning, lyrical and deeply reflective.” New Festival, NY, June 3-13, 1999

“An ambitious and provocative blueprint for love and death in the 21st century, this six-part journey through the body rubs up against American pop culture, archival porn and home movies to find a room of its own. Poetic and sensual, this is a kaleidoscopic exploration of AIDS, death, sexuality, memory, spirituality, relationships… Hoolboom sets the tone with Positiv; a monologue about AIDS told in four split-screens featuring pop-culture images, home movies and footage of visits to the doctor. A Boy’s Life follows up with a first person monodrama about a man fleeing from childhood sins into a masturbatory revel. In Eternity Disneyland is juxtaposed with a letter speaking about the white light after death. 1+1+1 is a pixilated black comedy about the relationship between a couple of devils. Poignant and playful, Moucle’s Island features Viennese filmmaker Moucle Blackout in a reverie which combines an older woman relearning childhood gestures with a nostalgic lesbian idyll. Passing On concludes the journey.” Ken Anderlini, Vancouver International Festival, 1998

“Canadian avant-gardist Mike Hoolboom’s Panic Bodies is an abstract meditation on AIDS, mortality, and the vulnerable human body. Likely to baffle or offend some viewers, it nonetheless offers complex aesthetic and thematic layers for discerning audiences to explore. Gay fests and experimental showcases are signaled. The movie is in six parts, each of which could stand alone as a short. One combines multiple images of home movies, medical reels and classic commercial features while a voice-over muses on loss of control over the body; others feature a masturbating man comically (and literally) losing his member and the reading of a letter relating a man’s protracted death from Parkinson’s disease. Last, longest and best section, Passing On, is potent enough to lend the whole feature a certain unity and sense of summation, as it poignantly mixes the personal, lyrical and spiritual. Hoolboom deploys a wide mix of visual tactics throughout, from borrowed footage to tinted, sped-up and upside-down images. Earle Peach’s sound design is equally adventurous. Though many viewers likely will find it too nonlinear, and perhaps too explicit in occasional sexual content, Panic Bodies rewards the patient with a deeply affecting afterglow.” Dennis Harvey, Variety, May3-9, 1999

“Mike Hoolboom is a sentimental cinematic predecessor to the late David Wojnarowicz. Divided into six sections, this feature races against mortality. Positiv sets the tone, its four-panelled screen barraging the viewer: Hoolboom shares intimate narratives and steals pop imagery, turning it into the stuff of dreams. Likewise A Boy’s Life moves porn from the rote ‘real world’ it usually occupies (tacky apartments, etc) placing it further into the subconscious. 1+1+1 accelerated identity-swap scenario is suffocating while its fluorescent color bursts are breathtaking. The final sections tap into the inherent poignancy of home movies. Spinning backward on a merry-go-round of memory in Passing On, Hoolboom stares at the viewer with a face that conveys many emotions. Merriment isn’t one of them.” Huston, San Francisco Bay Guardian

“An abundance of material is being used by Canadian Mike Hoolboom in Panic Bodies, a film of feature-length and one of the most outstanding films of the festival. From the very beginning he calls for the audience’s full attention, when on a split screen shots taken from Hollywood movies, video clips and home movies as well as the filmmaker himself can be seen and heard in his monologue on AIDS. The subjects of disease and death have been treated by Hoolboom in his previous films. Panic Bodies is composed out of various parts designed in different styles with the furious beginning being joined by the appearance of a performance artist. This part deals with the dramatic consequences of masturbation. In the next section, inserted text fragments derived from private correspondences depict a very personal story of two brothers, before one is allowed to drift into dreaming while watching scenes of a vintage porno movie. The cycle is closed by its longest part, re-introducing Hoolboom in a reflection on the loss of loved ones integrating home movies material. In spite of being in danger of falling apart, Hoolboom succeeds in keeping our interest alive because of his use of very diverse formal means.” Johannes C. Tritschler, epd Film, 7/99

“In a year full of Armageddons and an industry full of Cubes, it’s nice to see iconoclastic experimental local filmmaker Mike Hoolboom, two-time winner of the Toronto International Festival’s award for best Canadian short film, still doing his elegiac, hypnotic, emotionally grueling thing-and, even better, getting it shown (courtesy of those fine folks at Pleasure Dome). Four years in the making, Hoolboom’s latest-Panic Bodies-is a 16mm opus cut together from six different shorts, the longest of which clocks in at a svelte (by Hollywood standards) 20 minutes. Thematically, all touch on the personal and philosophical implications of his own HIV-positive status; qualitatively, they’re pretty much either brilliantly engaging or trance-like in their own inaccessibility. But the pleasures of the former, to my mind, far outweigh the momentary boredom of the latter. Stand-out honours go to Positiv, the program opener, which reproduces and elaborates upon the same quadruple-exposure hijinks Hoolboom first patented in Frank’s Cock, and Eternity, which uses a Steve Reinke-like combination of repetitive sound and image (light on water, birdcalls) and superimposed words to recreate a man’s last letter to a dying friend. The rest is borne on a boil of overlaid, self-referential and poetically repetitive imagery-stock footage, original material, home movie loops-which packs all the forlorn punch of shreds torn from a stranger’s memory: freeze-frame poetry, projected from the brain on outward. Hoolboom’s work continues to produce some of the most heartfelt, least common denominator commentary on Canadian culture available today. And much like this fever-dream we call life, the mere act of viewing Panic Bodies provides a truly unrepeatable experience, half transcendence and half tedium-a fleeting pleasure which we owe it to ourselves to savor as long as possible, before the inevitable fade to black.” Gemma Files, Eye Magazine, Oct. 8, 1998

“Having been diagnosed HIV positive, Hoolboom received a new impulse. The presence of the virus and its hiddenness evoke a chain of illusions and biological visions, new exercises in his film memory. The obsessive presence of sex/injury perseveres. However, it is no longer a shock of explicit nudity. Sexuality is an elegiac demonstration of incompatible, random beings. In the director’s version, the film undergoes the same kind of transformation (decay: film, a body without organs), but the loop of eternal return provides the film with a true resurrection. The film is divided into six parts. The opening section (Positiv) is the director’s collage of porn, popular scientific films, detailed footage of cells as well as sequences from classical films of big narratives. The picture is divided into four-one of them features the director and his soliloquy about AIDS that comments on bodies entangled in sex and death. The film’s second part (A Boy’s Life) is a bizarre kaleidoscope about masturbation and the loss of penis, an ironic reminder of men’s giant fear. In the third part (Eternity), a letter of Tom Chomont overlaps footage from a family archive. The words are suddenly more important than the picture. It is a long passionate confession about dying and light, which does not hurt the eyes. In an experimental ‘fiendish’ romance (1+1+1), a manual work with the film is dominant along with scratches, spilled paint and an industrial soundtrack. The work of Moucle Blackout, an Austrian filmmaker born in Prague, became an inspiration of an impressionistic idyll in the film’s next part (Moucle’s Island). Several decades old footage shows naked women at play. Archetypal nudist sweetness that evokes a remote innocence is an intermezzo, which precedes the final part (Passing On). The director’s suggestive confession is fully focused on death: fatigue is endless, the betrayal of the body (conspiracy of chromosomes) is irrevocable. There’s nothing left to do but compose a sad song in a long loop of solitary walks.” Jihlava Documentary Festival

“Panic Bodies consists of six parts or chapters, varying in length and style. Each suggests a new approach to these returning questions: what does it mean to have a body; to be a body, and what does this body want? Hoolboom appears in the framing chapters, and in between others take his place, submitting their bodies to a probing research. The treatment and effects of AIDS reform these subjects, but also the sexual body with all its desires and questions, and the almost dying body that can temporarily leave the world to be absorbed by what is called ‘the white light’ in Eternity.

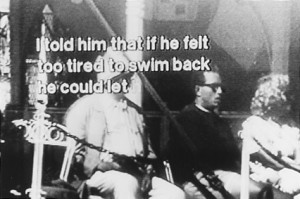

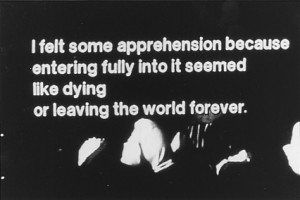

Voice-overs and intertitles alternate and speak sometimes in loaded (quoted) words, and then again in casual little lines like: “I am writing these thoughts because they relate to that moment in my kitchen when we speak and what happens to us.” This intimacy is typical of Panic Bodies. The voice speaks directly to the viewer, confessing, admitting, raising questions.

A theme that recurs over and again in Hoolboom’s work is: looking and being looked at; how we are using images, how images are using us and how our memory is mediated by all this. In Panic Bodies Hoolboom joins questions from and about our body and our relationship to our death, to issues of memory and the image.

Panic Bodies’s opening chapter, Positiv, shows the filmmaker in a small enclosure, speaking about becoming a body and AIDS. Around him three accompanying screens fill with the manic refuse of the mediaverse, providing counterpoint and juxtaposition to the flow of language. The second chapter is a wordless psychodrama, entitled A Boy’s Life, which shows a man in search. Beautifully photographed in close-up, this haptic quest narrative is shot from inside the body, out into a world which it also imagines as a body. The third chapter is entitled Eternity and features a video letter which appears over barely visible pictures made in Disneyland. The letter is by Tom Chomont, subject of Hoolboom’s next movie, and relates the death of his brother, and the white light which accompanies the beginning and end of life. The fourth chapter 1+1+1 is also the shortest, a stop motion romance repeated three times in successive waves of legibility, as two battling lovers arrive at a place where the Other becomes visible. The fifth chapter is entitled Moucle’s Island and features Vienna avant filmmaker Moucle Blackout. It rhymes her movements with the gestures of a small child, and then projects her into a dreamy sexual reverie. Each of the first five chapters might be read as portraits and these are drawn together in the concluding chapter, Passing On, which is the longest and most elaborate chapter. Elegiac in tone, the filmmaker returns to host a succession of vanishing friends and familiars in an avant-garde home movie that is also a ghost story.” Esma Moukhtar, Montevideo Catalogue

“The power of the dead is that we think they see us all the time… They are also in the ground of course, asleep and crumbling. Perhaps we are what they dream.” (Don DeLillo)

It is a movie about AIDS, the body, about living and dying. It begins, in positiv, with a monologue, which is metaphorically replayed in A Boy’s Life showing (again) a male solitary who tries to reconcile himself as a body of parts. Eternity is a film letter about the white light often experienced in near-death situations. 1+1+1 is a series of three variations on a couple trying to find their way together. Moucle’s Island shows a woman alone, recalling childhood, miming its gestures, and then slipping into a reverie of pastoral dykedom. Passing On is the closing note, an elegy and way of saying good-bye to those no longer here.

Positiv (10 minutes)

A monologue about AIDS, rendered in split-screens generously furnished with images from Terminator 2, science flicks, Michael Jackson and home movies.

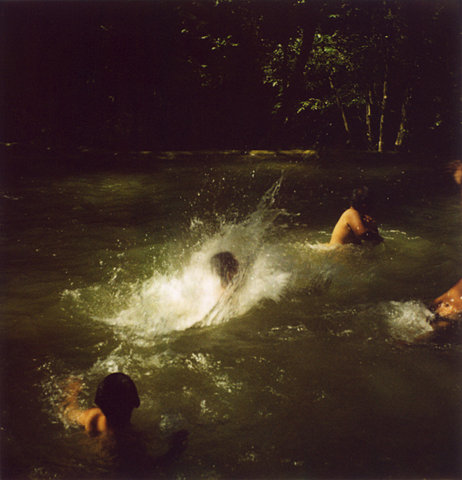

Positiv is for those who find TV too slow, though its roots lie in a multi-channel universe accessible by remote control. Its four screens play simultaneously. In the upper right hand corner a man speaks about the body and AIDS. On the upper and lower left hand screens a storm of pictures issue, culled from science films, rock videos, horror flicks and sci-fi movies. This montage of association features bodies grown large and small, frozen and burning, crumbling to ash and reforming, tortured and pleasured. On the bottom right hand screen, home movies show children at play, and then visits to the doctor, blood tests and drug inhalations. Here the body has been divided, cracked open, its myriad reflections in the media allowed to issue like an open wound.

A Boy’s Life (15 minutes)

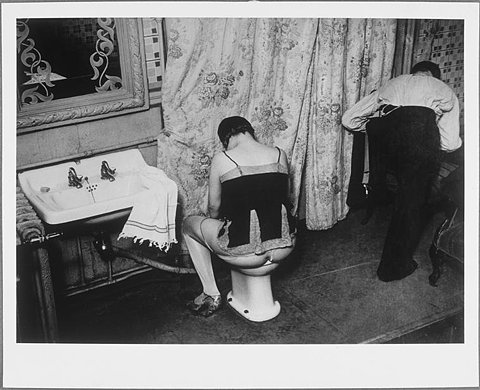

Featuring Toronto performance artist Ed Johnson, this first person monodrama shows a man in flight from the sins of his childhood, his attempted escape through a masturbatory revel that is so shattering he loses his prick, and his ensuing search for his missing organ.

Eternity (10 minutes)

A film in the form of a letter written to me by New York filmer Tom Chomont. In it he speaks of the white light after death, Parkinson’s, and his brother’s last moments in a New York emergency ward. The scrolling text appears over dark pictures shot in Disneyland, its architectures designed to stage the family, its dark inhabitants floating on rivers of light and sound.

1+1+1 (8 minutes)

“A pixilated couple plays dress-up and undress-up as Earle Peach’s industrial-strength audio track pulsates and ebbs with churning tides of sound.” (Geoff Pevere, Images Festival Catalogue)

Devils fall in love in Seattle in a black comedy of sex, machines and flight. Photographed a frame at a time over three days, 1+1+1 casts Boughton and Ramey as unlikely lovers, the first appearing as a hovering devil in flight, excreting a vegetable life, while Ramey’s clock-spitting, bathing-besuited countenance lifts weights in a frank measure of indifference. Their touch promotes a shimmering aura of light, a celestial forcefield which they lash against, finally retiring to the kitchen with a gaggle of tools to fine tune desire. Donning each other’s clothes, they fly off together to the strains of Strauss’s Blue Danube Waltz.

“Howling sirens and film which seems to be burning evoke the violence of war. From the ruins of the images, a man and a woman gradually emerge. Without a word but with a powerfully suggestive soundtrack, Hoolboom sets the stage for a strange dry-humoured theatre. Particularly daunting is the role of the woman who ironically delights in doing violence to the man. With its great formal inventiveness combining accelerated sequences and pixilation, this film is as jarring as the lives of many couples.” Jean Perret, Visions du Réel

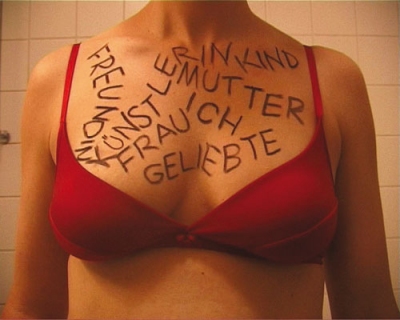

Moucle’s Island (12 minutes)

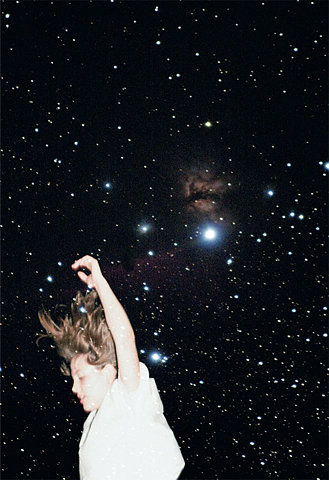

Featuring Viennese filmmaker Moucle Blackout, this all-woman reverie centers on two kinds of recall, the first to childhood where the untrained early gestures are re-learned as an older woman, and the second in a lesbian idyll, looking back in joyous nostalgia at a geography that might bear, if only for an afternoon, the impress of one’s own naming.

Passing On (20 minutes)

“Children playing emerge from overexposed film spoiled by time. It is snowing. These solarized images deal with memory in this film of maturity by Mike Hoolboom. The tone is serious; his voice evokes his brother, his parents. The people appear on the screen as though they were disappearing. Hoolboom records the loss of loved ones whose features he stares at with lasting affection. Beautifully simple recurring shots of the white square with black lines crossing it represent the realm of the hereafter, where the ghosts go. With contained and poignant lyricism, Passing On addresses itself to death as something familiar, death which prowls and throws into relief the images of a cinema trying to resist another death, no doubt worse, a white death of memories forgotten, without images.” Jean Perret, Visions du Réel

“Passing On was the densest and most exciting experimental film in Oberhausen since Pat O’Neill’s Water and Power in 1989. The reflections on death, mortality and our common fate of passing are expressed in a technical sophistication and mastery rarely achieved by other filmmakers. Images in a deep sepia tone never seen before on screen are combined with refined multiple exposures and outstanding compositions. On the same level of quality are the poetic eloquence of the reflections and the sensitivity of the voice-over. Mike Hoolboom from now on has to considered equal to filmmakers such as Maya Deren, Stan Brakhage or his fellow-countryman Michael Snow.” Georg Immich, Film + TV Kammermann, issue 6/98, June 98

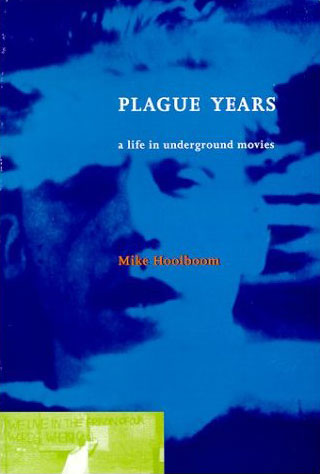

“Portrait of the filmmaker as a busy young man” by Liam Lacey (Globe and Mail Oct. 10, 1998)

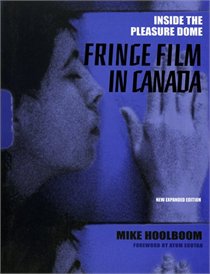

Experimental filmmaker Mike Hoolboom is a prolific figure, but tonight he outdoes himself: he’s unveiling both a feature-length film (Panic Bodies) and a book (Plague Years: A Life in Underground Movies) which blends film scripts and autobiography. Hoolboom has made more than 25 films (and more than 40 if you count the pieces out of which some of his movies are assembled) in the past 18 years, shown his work in more than 200 film festivals and twice won the award for best short film at the Toronto International Festival. Often cited as one of the most important Canadian filmmakers of his generation, Hoolboom is also one of the best chroniclers of other fringe filmmakers. He has written more than 80 articles and essays for film journals, and his book Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada has an introduction by Atom Egoyan, who cites Hoolboom as one of the filmmakers who inspired him.

If there has been a quality of urgency to Hoolboom’s output, it’s understandable. Ten years ago, after going to donate blood, he discovered he was HIV-positive, an event which he writes in his new book, “did wonders for my film production, and while my earlier movies were slow open fields where viewers might graze and push on, the new work turned behind a different pace car.” In the two years following, he produced ten films which he describes as characterized by a “frantic, near hysterical montage, with bodies shattered into parts, and an underlying feeling of dread.”

The pace has barely slowed, but the frantic quality is less evident. At 70 minutes, Panic Bodies might even be described as his first feature, even though it consists of six separate films. It represents four years of work and a demonstration of a wide variety of approaches to one prevailing concern, the fact of living in a body. You can think of it, says Hoolboom, “like an accordion that folds out, and shows you all the different bodies you’ve ever been. Like a body, the film has different parts. It’s a film that deals with AIDS, which fragments the body, so it’s a film of fragments.” The film shows Hoolboom speaking directly to the camera in one of four separate films running together on the screen. Sometimes it uses images from Hollywood movies and rock videos, home movies, vintage porn, a pixilated pantomime between a man and woman in a kitchen, or scenes of people masturbating. One segment puts on the screen the text of an entire letter from a friend, about watching his brother die. The fact of being imprisoned by an aging body is the subject of another. In a segment entitled Moucle’s Island, Hoolboom decided to do an experiment with a friend, Moucle Blackout. He asked her to move again as a child, filming her crawl through tunnels as if they were a birth canal, and later intercut images of children climbing into chairs, added an old porno film of women frolicking and finished with a shot of Moucle masturbating while being washed in water.

Occasionally, in Plague Years he writes of filmmaking as a kind of mourning, although mourning, as he explains it, is not quite the same as grief. “Filmmaking is inherently an attempt to capture something that disappears,” he says. “It’s a recuperative business. There are early playbills for movies which declaim a promise that, with the coming of sound and colour, death itself would not be so final.” From experimental filmmaking, Hoolboom believes, there is a model of future relationships, of intimacy constantly being mediated through technology, pushing the boundaries of sexuality and taboos. “We’re moving to a different kind of post-literate world. Readers are like books: they’re private. You can’t tell a book by its cover. What the postmodernists are always on about, is how we’re becoming a world of surfaces with no interiors, no private lives. I really think we’re heading that way.”

Hoolboom, for his part, is bucking the trend. Currently, he’s writing a novel. “It made me realize that filmmaking is ninety percent running errands. With writing I just need to stay close the place where the words come from.” As a filmmaker and a champion of other filmmakers, he’s driven by a couple of motives. One is the reluctance to makes films that are more of the same in a world too full of copies. “It’s a way of saying no to the Titanics of the world.” It’s also a chance, on a grander level, to talk about the growth of consciousness. “When you were a kid, and the career choices were offered to you-doctor, policeman, fireman-no one ever mentioned “artist.” I’ve been back to my old high school to talk to classes. I’m fascinated how one person’s original idea can becomes everyone’s. There were notions that were only the province of a handful of people 300 years ago that are now taught in high schools. When it comes to exploring what’s new, fringe film glows very brightly.”

“Panic Bodies: A Blueprint for Love and Death in the 21st Century” by Tamara Faith Berger (Lola Winter 1998)

Panic Bodies is built like a body-a copulation of six films conceived as a whole. It has its head and feet (Positiv and Passing On), and its viscous guts (A Boy’s Life), pumping blood (Eternity), hairy skins (1+1+1) and fat cells (Moucle’s Island). In this body, memory and physicality are intertwined—the head cuts off the feet, the feet stomp the head, and the innards churn and beat, erupt and erode. If Panic Bodies is a film about this body dying, it is amazing because this body is speaking fearlessly. If Panic Bodies is a movie about this body living, it is amazing because this body is telling the bedtime story of death. Within this elliptical form, Panic Bodies becomes both horror and narrative. In one sense, the filmmaker is the slashed-up victim, running through the streets ten feet behind the camera, horrified, bleeding, and holding the weapon he wrestled from his murderer, screaming, “Come! Look at me! Help me! Save me! I almost died!” And at the very same time, the filmmaker is the yarn-spinner whispering to the audience, “I am talking to you, look what I have seen, look what I have known, I am showing you my wounds as they are opening and closing…”

Experimental filmmaking usually opposes the structure of mainstream filmmaking, which doesn’t need the participation of the audience to tell its tale. Experimental filmmaking (of which Panic Bodies is a torch-setting example) wants to bring the audience closer to its process and performance, so it can implicate them with every new image and utterance. It follows that most experimental films are not 70 minutes because most makers do not have this much faith in (implicating) their audience. Faith, however, is the quality that unifies Panic Bodies. (This is more startling than one might think.) Hoolboom’s faith in communicating with his audience generates a strange kind of empathy as the audience sits in the dark and watches his throbbing constructions. This is the dis-ease of Panic Bodies—the feeling that we are all dying together. I’m not sure how, but somewhere in this revelation, I meet my equal. I can walk with him into the screen. I have never felt this before.

Panic Bodies embraces me even if I don’t want to be embraced. I think this experience of cinematic conviviality runs counter to what Hoolboom himself believes about the deathliness of images. He says that there is something inherently deathly about cinema because the link among all movies is that everyone in them is dead or will pass on. Yet Hoolboom’s film invited me to be vivid-to be as potent and as sad, as full and as sick, as aggressive and as tender, and as urgent as he was, and as his film was. I was not mourning for the passing on of images because I was overcome with the memory of what sadness feels like.”

“Fringe Filmmaker Flaunts Subconscious in Ode to Mortality” by Cameron Bailey (Now Magazine cover story, Oct. 8-14, 1998)

Mike Hoolboom leans back in his chair and confesses. “I had this dream over the weekend.” Behind him, a bloodied mannequin child protrudes from high up on the wall. What’s that about? I never ask. “I hardly ever remember my dreams,” he says. “I’m underground, putting together two small buffed metal pieces. One has a small stick shift on it which makes for a very satisfying motion. They snap together with a magnetic charge. I do this over and over on a long conveyor belt. I realize that all the things I do in my life-talk, hang my friends, fall in love, answer the phone-are all coming from this action. It all boils down to this. Then the camera zooms out and I see that there are millions of people around me and they’re all doing exactly the same thing. We’re all putting our little metal pieces together. I have this great feeling of communion. We’re all one person after all. At that moment the spotlight shines down on me and I’m scooped up in a net. I look down and realize I’ve been replaced by a machine doing the same thing. It’s putting together the metals, and I scream, ‘No robot could do what I do!’ But of course it could.” He searches me for interpretation. “Anyway that was my dream.”

Welcome to Mike Hoolboom. Even his dreams come with camera cues. Hoolboom is one of the world’s best at what he now calls fringe film. They lavish him with retrospectives in Europe. His films play everywhere people demand more from a movie than escape or information. He’s shown more films at the Toronto International Festival than any other Canadian filmmaker. He’s won the award for best Canadian short twice, for Frank’s Cock and Letters From Home. Hoolboom started out when ‘fringe’ was ‘experimental’ and it was all about exploring the tangible qualities of the medium-focus, grain, time. Its highest principles were abstract. But over the past 18 years, his films have evolved from aggressive aesthetic experiments-jumping geometry in Grid, a blank screen in White Museum-toward something both larger and more intimate. He’s telling stories now. He’s put his subconscious on display. The body of his work ranges from the gentle study of light and shadow that underpins Eternity, a part of Panic Bodies, to a ferocious streak of transgression in Shiteater, one chapter of House of Pain. More and more, Hoolboom’s films weave confession, polemic and pure visual poetry into something beyond the fringe. More and more, his work is shaped by the fact that Hoolboom has AIDS. Outside his window, huge construction machines plow steel pillars into the ground. They’re building condos. This is something robots can do. “I think my early movies were like a long handshake with the medium,” he says above the noise. “But after becoming positive, it became incumbent upon me to make work that tried to deal with the things that came up-like mortality and this very odd, new place that my body was in. You look in the mirror and you’re one person because you’re one body. But all of a sudden, you’re not one body any more, because parts are filled with this foreign thing. So maybe I’m more than one, I mean, in the act of contagion, where does one body begin and another end?”

Ten years ago, a doctor told Hoolboom he was HIV-positive. He gave him some pamphlets. “I wasn’t certain how to proceed,” he recalls wryly, “but I imagined that the end was not far. In a way, it fit in with how I was living anyway-kinda fast, thoughtlessly, drinking too much, not too… reflective. I just kicked the accelerator into everything I was doing. Made more films. Did more work. Repressed as much as I could and tried to fill my days with stuff. Activity. I got an enormous amount of work done.”

Hoolboom cranked out film after film. He took a job as the experimental film officer at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Center. He helped create Pleasure Dome. he began editing a new journal, The Independent Eye. “But I was living in a hysterical state. It took leaving Toronto to finally get some distance.” In 1990, Hoolboom began a three year exile in Vancouver. “I moved to a city where I knew nobody, and was alone for a year. I stopped all the drinking, saw another doctor and tried to eat differently. My (T-cell) counts were falling. I knew I had to do something.”

His work changed in that time, but it didn’t change into just one thing. It expanded. He collaborated with Kika Thorne, Steve Sanguedolce and with Ann Marie Fleming, each of whom brought new colours to his work. He made Kanada, an experimental feature about a future where people with AIDS were quarantined by the Gretzky government. He discovered Madonna.

Hoolboom’s recent films often throw pop culture up against avant-garde rigour. He’s mined the Madonna image trove at least three times, and his new book, Plague Years, includes a hilarious fake memoir of meeting the goddess-commodity in high school. To Hoolboom, aesthetic isolation is for fools. He thinks of how the marketplace has swallowed fringe film techniques and snorts. “Hand processing? The National Football League uses that for its promos now. The only thing that’s avant-garde is commercials. People with money are in the avant because they know where we’re going. It’s the 90s. People are following money. And yes there are these eruptions of dissent, and that seems to belong to the fringe.” But he insists, “Fringe film is so valueless now. Its ideals belong to another time. It’s like a hangover of the 50s beat, pseudo-anarchistic thing, coupled with 60s social movements.”

So this is the end of an era.

“It’s so clear now. There’s one lab left in town that will do colour 16mm film. There’s one guy left who knows how to do opticals. When he’s gone, you won’t be able to get those done in Toronto anymore. I’d be shocked if 16mm lasted more than a couple of decades.” New times demand new methods. So Hoolboom is doing something fringe purists usually scoff at. He’s listening to his audience. “I took Panic Bodies through a test run in Germany,” he says, ” It played in half a dozen spots, and in the last place I saw it, I knew what was wrong with it. So I recut one section, a lot. Remade the music and sound effects and started shooting again. Cut some more and kept at it. I’ve spent most of the last three years recutting my films,” he admits, “House of Pain is down to 50 minutes from 80. Kanada is down to 45 from 60, and then I threw it out. Valentine’s Day went from 80 minutes to 18 before I threw that one out too.” As he remakes his past films, Hoolboom keeps pushing the limits of his future work. Since he released his searing eight-minute Frank’s Cock in 1993, his films have confounded notions of queer against straight, cerebral against emotional. Now he calls his films “documentaries of the imaginary.” “They’re more faithful renderings of how I dream, or imagine the world to be, or imagine my place in it,” he says. “In my dreams it’s normal for me to become a woman, who becomes a man, who turns into a table. Gender is not such a fixed thing. That’s more reflected in my work now.” Hoolboom has always been his own severest critic. But the way his recent films, especially Frank’s Cock, have reached people emotionally is what keeps the fire burning now. “I needed to try harder, make better work,” he says. “The feeling that I got in the theatre was unmistakable, it was so good, and I wanted more of it. It was a reminder that you can out razzle-dazzle the best that’s ever been, and people may applaud politely. Or they may leave. But if you can connect and move people, that’s film. It’s the magic of sitting with all those people in the dark and giving yourself over to the light.”

“Stranger In A Strange Skin” by Kathleen Pirrie Adams (Xtra, Oct. 8, 1998)

Death is inevitable. And death has an aesthetic. Disease only claims the latter. For underground filmmaker Mike Hoolboom the advent of HIV and AIDS has place the challenges of disease and dying centre stage. It’s a personal issue, a social issue, a question for art. His response over the last decade has been a powerfully creative one. Hoolboom is perhaps best known in the queer community for Frank’s Cock, an intense elegy for a lost lover built around a monologue tenderly delivered by Callum Rennie. Then there’s Hoolboom’s Madonna video remakes (Dear Madonna and Justify My Love), which push the desperate longing of the fan right into the idol’s frame.

His latest work, Panic Bodies is a 70-minute, six-part exploration of the ways we experience the body’s betrayals: disease, decline and death. The film is a panorama of emotionally charged recollections of strange relatives and estranged siblings, staged recreations of fast-fading pasts and personal mythologies, and reflections on the anxious states created by the body’s fragile claims on time and space. It’s about being a stranger in your own skin. Panic Bodies perfects the phantom quality of any good work about mourning, but it is not reducible to that. It is also enlivened by the intimacy that comes from having made a spectacle of personal secrets—as much a tradition of gay art as, say, irony or camp. And it is filled with beautiful editing that pull teen-angst icons Matt Dillon and Mickey Rourke into the artist’s own story of leave-taking, or that match vintage erotica with childhood games.

The complex whole is held together not just by its recurring themes, but also by its studious attention to the luminous beauty of the film image and its lyrical use of shades of blue and orange. Even so, not all parts are created equal, and each viewer is bound to revel in some sections and reject others. The first part, Positiv, bears the closest resemblance to Frank’s Cock. using a four-part screen, it sucks in fragments of its super-saturated image-environment: home movies, medical footage, Hollywood blockbusters, and the artist’s diary of domestic routines and trips to the doctors. Although at first it looks like the medical will steal the screen, in the end, it is the insistence of imagination that wins out. Perhaps one of the most powerful moments in the sequence is when the narrator creeps into the hole in the head of the “other”—the uninfected—where he hears the empty echoes of the clichés of responsibility and self-determination. “All this could have been avoided if only you’d been a little more careful…” It’s the moment when the armor of judgment and rational risk-calculation retreat, when AIDS becomes, as Steve Reinke writes in the introduction to Hoolboom’s book, Plague Years, “not a disease, just another compelling symptom of a diseased lifestyle.”

Moucle’s Island is another intriguing chapter of Panic Bodies inquiry. Found footage of a baby’s birthday party and a nudist sailor girl frolic are intercut with shots of an older woman crawling along paving stones, rolling across a pebble beach and with great effort, up a concrete furrow. The Kodak moments and vintage erotica wind a 30-year string of cinema history around the time-worn body of Hoolboom’s colleague, Viennese filmmaker Moucle Blackout.

Panic Bodies pushes beyond panic without abandoning its own basic mission: To record life as it is lived in a world where stains don’t just disappear with one cool shake of the tail. For those afraid of non-narrative film or fearful that the deeply personal will embarrass either the artist or the audience, Panic Bodies is probably not going to provide a conversion experience. But for those who think it’s interesting—even necessary—to think about what disease and death mean for the psyche or for culture, Panic Bodies will demonstrate how bloodletting can possess a magic comfort.

“Panic Bodies: The tragedy of the temporal dominates the work of this gifted Canadian experimental filmmaker” by Gary Morris (Bright Lights Film Journal, April 1999, Issue 24)

In the opening segment of Panic Bodies (1998) Canadian filmmaker Mike Hoolboom talks poetically about the inevitable sense of displacement that accompanied his HIV diagnosis: “I felt like a virus that’s come to rest in this body for awhile.” But Hoolboom is no ordinary filmmaker, and Panic Bodies never succumbs to the gross sentimentality that marks much of “AIDS cinema.” He in fact finds a curious solace in his betrayer, as if a kind of body logic and pathos coexist with the disease: “My life possessed a shape after all, a unity, and that shape was my body.”

The beauty of the body and its tragic temporality are the driving motifs of this powerful six-part experimental feature (70 minutes). The opening segment Positiv, splits the screen into four smaller ones, with one occupied by Hoolboom monologing about AIDS and the other three filled with such varied treats as home movies, found footage, porn samples, microscopy and pop culture imagery from Michael Jackson to Terminator 2. Hoolboom is sometimes serious and sometimes mocking in his words (“I wanted to be a fat ice cream queen with nice skin”) and the bright, flashing images often play off them. When he talks about how “600 cells die in the body every day, and every six years we’re a new person” one of the smaller screens show a riot of microscopic cell activity. Typical of Hoolboom’s skill is his rapid intercutting of an atomic bomb explosion with a single hand, a telling image of the kind of individual apocalypse that, for the director, is woven into modern life.

A more whimsical sensibility emerges in the next segment, A Boy’s Life. Toronto performance artist Ed Johnson appears as a naked man haunted by his childhood (seen in fractured home-movie inserts) and even more, on his prick, which he plays with so much that it falls off. While Ed is busy searching for his lost appendage, Hoolboom is playful, reminding us of Ed’s quest with a cut-out penis shape through which we see the action. Of course, this is not exactly standard light fare. A scene where Ed eats a baby doll that’s been halfway up his ass recalls Goya, while scenes of multiple Eds masturbating (seen through a kaleidoscope are as unsettling as they are amusing.

The next part, Eternity, is a 10-minute exegesis of The End, in the form of a letter from Hoolboom’s friend Tom Chomont describing the latter’s experience with “the white light after death” and his overseeing of his brother’s demise. Much of this segment was shot in near-total darkness, as befits the subject; any illumination comes from the words, which again have a simple poetic resonance: “Then just at the last, concern for someone I knew pulled me back.”

Some of the works here are more accessible than others. The next segment 1+1+1 shows a drunken couple laughingly assaulted each other, dressing and undressing and generally carrying on behind Hoolboom’s opaque mise-en-scene, which consists of scratchy footage, colours that bleed all over the action, and a throbbing industrial soundtrack. But the director kindly shows us some of the same scenes again without the obscuring overlays.

Part five Moucle’s Island stars Viennese filmmaker Moucle Blackout in some of the action, but most viewers will be more intrigued by interpolated ancient footage from some forgotten Naturist epic of the 1930s. This one turns a mock-innocent boat cruise and naked volleyball game into a blissful lesbian idyll, with the coyly cavorting women an ideal symbol for Hoolboom’s obsession with the sweet moment in which the body is free, even if only in an old porn film.

The last, and longest, segment is Passing On, a lyrically typically confessional effort that encapsulates what’s preceded it. Hoolboom’s dance with death-a motif acknowledged in the medieval woodcut segues between segments-resonates in double-exposed shots of anonymous people simply crossing a square, some of them “real,” others shown as faint, literal “ghosts” co-existing with those still in the temporal present. In voice-over Hoolboom talks about the “conspiracy of chromosomes” that make up the human being, the phrase is ironic; for him, nothing is more real, or human, or felt, than what that conspiracy has created.

Looking for Troglodytes: an embodied rumination on experimental cinema by RL Cutler (Front Magazine March-April 1999)

December 20, 1998 was a cold and bitter day. Xmas was around the corner and, unusual for Vancouver, snow was on the ground. I needed a diversion, from the December consumerfest and so, on that freezing Sunday afternoon, I made my bundled way to Gastown. I had discovered that Mike Hoolboom’s Panic Bodies would be showing at The Blinding Light Cinema, that fabulous fringe cinema space. I had heard his work mentioned many times by the film buffs and hipsters who populate this metropolis, sequestered in their non-profit offices, or critiquing from sofas from both sides of Main. This was my chance to see the work of a respected, contemporary experimental filmmaker, and I would not let snow, nor sub-zero temperatures get in the way of the experience.

I thought that Mr. Hoolboom’s work would be able to entice more urban troglodytes from their bunkers. But upon entering the theatre, I quickly realized that I was on my own, quite literally, in this crazy peccadillo. Just as the show was about to begin, my solitude and reverie were punctured by another spectator entering the dimly lit space; here I thought was a comrade seeking solace in the comfort of strangeness and cinematic form. But, alas, he belonged to a different breed of troglodyte and left the theatre half-way through the film.

In the introduction to his book, Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, Hoolboom cities Barthes’ description of leaving the movie theatre: “The subject who speaks here must admit one thing: he loves leaving a movie theatre. finding himself once again outside in the illuminated and half-empty street (somehow he always goes to the movies on weekdays, and at night), limply heading toward some cafe, he walks in silence (he does not care much to talk after seeing a film); he is stiff, a little numb, bundled up, chilly: he is sleepy irresponsible. In short, he is coming out of hypnosis.” Roland Barthes, Upon Leaving the Theatre

Hoolboom interprets this passage as an example of the collective dream produced by the cinema experience, sitting both alone and together in the dark. On this cold afternoon there was no communal experience nor group anonymity within the Blinding Light. Through a haze of hypnosis and somnambulism, Barthes’ Paris facilitated a saunter to the local café. Vancouver’s cold air inflected my own narcosis of reflection, en route to my rental cave.

As the publicity points out, Hoolboom’s film celebrates the complexity of themes addressing the life of a body. “Drawing from sources as varied as hyped-Hollywood, obscure 20s porn, and his own treasure trove of gorgeously shot original footage, Panic Bodies is a complex and visually arresting study of life, love, death, family, obsession and being a stranger in your own skin.” I was particularly interested in the elliptical and synthetic form Hoolboom developed to impart this vision. It integrated a range of techniques and modes in order to describe the complexity of human experience. The hybrid nature of Panic Bodies signals a fusion of past experimental styles into a synaesthetic effect. What appears to constitute contemporary experimental film is a combination of technological innovation, challenging subject matter (libidinal and excessive where possible), and space for reflection. To this end, Panic Bodies can be situated inside a broader consideration of experimental film.

During the last few months of 1998, I accepted the task of teaching studies in Experimental Animation/FilmVideo at Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design. It seemed epistemologically necessary to come up with some definition for experimental film. Not surprisingly, there is no single description for the subject. Its various labels highlight this: avant garde, poetic, visionary, materialist, formalist, conceptual, fringe, alternative and of course underground. These terms reflect the often heated debates circulating at the time of the film’s initial screenings and they resonate very disparate agendas.

Since film became a cultural product at the end of the last century, experimentation has been central to the practice. Consider George Méliès fantastical play with editing and special effects. Although the Lumiére brothers’ projection of still photographs provided the illusion of movement and writing of light, theirs was more of an experiment driven by scientific curiosity. While new technological features have always excited the makers of time-based media, “a horizon line of the real, a line separating the simply visible from the impossible” distinguishes truly cinematic work. The surrealists, progenitors of experimental film, understood the fragmented ontology of moving images which allowed for juxtaposed scenarios and imaginative aesthetics. Maya Deren, with her surrealist and ritualistic sensibility, demonstrated how space, time and illusion were the perfect subjects for film By the fifties, experimental film had been influenced by the progress of modern art, specifically highlighting a self-reflexive and formalist agenda. To those who appreciate the non-commercial, experimental filmmakers can stretch form and content making new experiences for the embodied mind.

Although there is a large and diverse output of experimental film, it is difficult to actually view these time-based objects. While paintings and sculptures take up residence in galleries and museums, screening ‘art films’ is still a tricky venture. In part, the paucity of venues for experimental film is due to problems of funding, distribution, and a colonial unconsciousness. By this I am suggesting a uniformity of cultural and social experience that colonizes the imagination.

What makes films like Hoolboom’s so fascinating is that they do not simulate reality nor the reality of mainstream film but articulate an alternate or parallel consciousness. Many experimental films have imbibed the evolution of film production and employ various strategies or modes of visual experience. Narrativity is fused with the awareness of one’s own perceptions. “Thus one invests the experience with meaning by exerting conscious control over the conversion of sight impressions into thought images.” Experiments in material construction are juxtaposed with political and challenging content.

Panic Bodies was a treat in that it fused the numerous styles of experimental film into a millennial hybrid, weaving sharp observations with aesthetic wonder. Structurally, the film was separated into six vignettes, each preceded by a black and white etching of a Renaissance subject and a title, including Positiv, Passing On, Eternity, 1+1+1, Moucle’s Island and A Boy’s Life. Part personal narrative, part libidinal spectacle, and with an arsenal of visual pyrotechnics, Hoolboom’s film challenged the viewer to participate—to become embodied. The scourge of AIDS on the narrator’s body elicited personal recollections of the body in pain. This is a film about death, which means that sex is never far behind. The libidinal was explored both in a kaleidoscopic vision of penis play and the jouissance of vulva masturbation. Both scenarios were mesmerizing especially due to the jarring soundtrack that accompanied them.

I had hoped to encounter other troglodytes on the my way to the cinema. None had emerged, and on my way back I had occasion to reflect on the nature of that day’s experimental film. Hoolboom’s Panic Bodies is a death poem in six acts, representing a body in pain and a body in life. Though the air was bitter when I left the theatre, the body that carried me home was alive in the cinematic afterglow.

Hoolboom ranks with Snow, Weiland, Cronenberg by Peter Goddard (Toronto Star, Friday Oct. 9, 1998)

Panic Bodies, the Mike Hoolboom film at the Art Gallery of Ontario’s Jackman Hall tomorrow night at 8pm and Sunday at 2pm, goes through hell to get to where it wants to be. Hell is the here and now. It’s the funny/toxic/grotesque media-blitzkrieg bombing Panic Bodies split screen—and our heads—for the first ten minutes of the films 70 minutes length. The section is called Positiv. Fans of Hollywood’s kind of narrative filmmaking might not want to deal with this mountain of visual rubble which is piled higher and higher on the imagination. It’s as daunting as the hot sex bits, Terminator snips and sci-fi clips careen into a heavily treated segment of a Michael Jackson video which in turn morphs into something else. Even indie-film fanatics may get twisted around by Hoolboom’s manic montages, which are mostly a riff on the real music to come. With this bravura visual set-up, Hoolboom gives us exactly what we’d expect from an adventurous filmmaker who has won a number of awards for two of his previous efforts, Frank’s Cock (1994) and Letters From Home (1996).

The image barrage is the nightmare before the dream. And this is a dream, a film, a meditation on the after-life that’s as powerful as anything in cinema. In fact, to go ever further out on a critical limb-Panic Bodies, a companion to the filmmaker’s recent memoir, Plague Years, is one of the truly defining movies in Canadian filmmaking history, a genuine successor to Michael Snow’s pioneering work, Joyce Weiland’s Water Sark and David Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers, just to name a few of the more visually-charged films the country has produced.

Neither of the program’s co-presenting groups, the Art Gallery of Ontario and Pleasure Dome, put any qualifiers in its all-out praise. Hoolboom is described on one press release as “the most important Canadian filmmaker of his generation.” Hype like this might be expected from institutions hoping to drum up business, particularly for someone like Hoolboom who’s less than a household name. But in his case, they’re mostly right. Hoolboom’s influence on alternative filmmaking has been enormous as a filmmaker, an arts-organizer (who helped start Pleasure Dome) and as a theorist (Fringe Film in Canada, published last year, has interviews with many of Hoolboom’s alternative film peers).

In some ways Panic Bodies continues Hoolboom’s thinking about gay culture in a high-tech world and reflects his deeply-felt autobiographical urges. Yet in many more ways, it goes an enormous distance beyond what we saw in Letters From Home, as the five sections which follow Positiv flow visually and intellectually away from the opening’s scarred and tattooed surface. In Panic Bodies the look and the very idea of the film mesh. “Ever since becoming HIV-positive, I’ve felt like a virus that’s come to rest in this body for a while,” goes Hoolboom onscreen, only as a distant face floating in the screen’s upper right-hand corner. “That it really doesn’t belong to me anymore. Like I’m trying on a new suit that won’t fit.”

Elegiac in tone, Panic Bodies is Hoolboom’s own out-of-body experience, section after section. In A Boy’s Life a man (performance artist Ed Johnson) masturbates away his youthful guilt-and loses his penis in the process, only to fish it back again. (We’re talking about a real hook on a real line. The penis, one hopes, is not for real). Eternity meditates on death’s seductive grace. 1+1+1 turns modern romance on its head, with a slamming techno-track and a pair of happy, hammer-wielding lovers. Moucle’s Island is a wonderfully dreamy feminine sexual fantasy, with some vintage porn. Passing On is about memory itself. Not everything works. Some of the jokes-the penis-fishing bit for one-fall flat. The repetitions in 1+1+1 feel just that: repetitive. But what a great motion picture!

Film so good, it ruined my day

Highly personal work looks at the diseased boy and the filmmaker living inside by Mark Caughlin (Manitoban April 7, 1999)

Perhaps the best thing about experimental filmmaking is not so much the startling originality of the visuals, but rather the highly personal tendencies of the form. And when the creator of such films is living with AIDS, the touch of death tends eventually to find its way into that author’s films. Diagnosed as HIV-positive ten years ago, Mike Hoolboom kicked his filmmaking into high gear at the time and, by his own account, repressed everything he could.

Panic Bodies, however, marks a turn toward a calm, bold candor: it’s a meditation on flesh, on death and on the disease inside Hoolboom’s body. It’s equally a set of hallucinations, an exercise in memory and an elegy to himself that (of course) recognizes his own continuing existence. While the experience of watching Panic Bodies one afternoon left me depressed for the rest of the day, it did so in a meaningful way. The film avoids being emotionally manipulative, making its impact in a way that only a well-crafted film can. Hoolboom may address the audience directly, he may flaunt nude bodies—both healthy and lesion-ridden—but he’s not out for his audience’s sympathy, nor is he out to shock. Rather, he’s groping towards understanding, and he’s sharing that process with an audience. But while he’s considering a whole range of questions besides disease, the body is clearly at the forefront. In the last section of the film, for instance, he contemplates the fact that, as humans, we are contradictory, incoherent beings. Ironically, both our memories and our existence itself are anchored by our body, which is at once our most fundamental imprint, but also the part of us most subject to vulgar decay.

For the filmmaker, film stock is equally the most important imprint—however fragile. In Hoolboom’s hands, it undergoes the same sort of mutation experienced by the body. The Vancouver-based artist shoots new footage and mines home movies and other found images, then processes, blurs and cuts them up, all in order to make things both more personal and more detached and, above all, to re/member. Critics like to highlight the fact that Hoolboom uses footage culled from rock videos, porn and documentaries, but aside from the film’s first section (Positiv), the found image that he uses are not so much pop-culture cut-ups as they are integral—if contradictory—contributions to more extended meditations. And because death doesn’t often come in the form of a dagger in the guy right before the curtain, Panic Bodies broaches its topics idiosyncratically. Divided into six distinct parts varying from 8 to 20 minutes in length, the film comes together in an uncertain whole. In the first segment, the screen is divided into four sections. In one of them a man (Hoolboom himself, presumably) delivers a monologue about AIDS. The accompanying sets of images ironize, (de-)contextualize and expand on what’s being said and felt.

A Boy’s Life, like Moucle’s Island, begins by using the body as a canvas and a mirror, before becoming the story of a man who loses his penis. Moucle’s Island, by contrast, moves into the realm of 20s/30s lesbian fantasia. Hoolboom reduces film stock shot in Disneyland to flecks of light and deep shadows, focusing primarily on sounds of lapping water in Eternity. Over the visuals, he scrolls a letter from a New York filmmaker that talks about seeing the “light” and his brother’s own death. Hoolboom calls his films “documentaries of the imaginary.” As such, this film belongs firmly within the “avant-garde” camp. But it’s not only worth seeing because it’s aesthetically on the edge, arty, or because it makes you think—although it does—but more importantly, because it makes you feel.

Worth its Weight” by John Griffin (Montreal Gazette, Feb. 4, 1999)

Toronto filmmaker Mike Hoolboom’s Panic Bodies is a 70-minute portrait in six parts about life, AIDS, death and memory and our ultimate corporeal betrayal by time, disease and decay. It is not Toy Story 2. It is, however a profound reverie upon the impermanence of all flesh and the powerful pull of whatever comes after we have shuffled off this mortal coil. Less feature film than collection of found or retrieved objects, Panic Bodies feels like treasure unearthed in a loved one’s attic after the loved one has left. It is the key to the sanctuary of psyche.

Hoolboom’s most recent opus was three years in the creation and is divided into separate pieces of a whole. It begins with Positiv, a monologue about AIDS told on four screens with images from Terminator 2, science films, Michael Jackson and home movies—to name a few. Next is A Boy’s Life, which features T.O. performance artist Ed Johnson, Ed’s johnson, the sins of childhood and the possibility of escape through what your priest called self-abuse. Eternity is a film in the form of a letter written to Hoolboom by a friend in New York about the afterlife. And 1+1+1 follows a couple dressing and undressing against a soundtrack wall of industrial noise by Earle Peach. Moucle’s Island is an all-women daydream featuring Viennese filmmaker Moucle Blackout, while the final segment, Passing On, is an elegiac, hypnotically rhythmic look at family history seen through over-exposed film, as if from a great height, or a greater beyond. It is strange and familiar and almost unbearably sad.

Panic Bodies can make for some heavy emotional sledding and might drive those unused to experimental filmmaking to the wall. But those willing to be carried by it will find the experience fulfilling, fraught with identification and quite unforgettable—which might explain why such a theoretically difficult piece won the Telefilm prize for best Canadian feature at the last Festival of New Cinema and New Media here. Great art will out, regardless of content.

Hoolboom isn’t modest about Panic Bodies. He isn’t boastful about it, either. Speaking from his home in Toronto this week, he seems to regard the work as an extension of himself, something he does because he has to. It is who he is right now, in the way that earlier short and medium-length films like Frank’s Cock, Kanada and Valentine’s Day were him in the early 1990s.

“The film represents a lot of work over a lot of time. it was made cheaply, with portraits of people and parts of my life. It’s like a deep and intimate talk between friends before going off to our own solitudes. For me, it’s a way to reconfigure the world and find a shape to everyday life.”

Hoolboom slips into the mystic when he explains that “the finished film exists before I make it. The journey as a filmmaker is to find the place where it is. The piece has inclinations and rhythms of its own. You have to listen to find them. Listening is central.”

He says Panic Bodies and his life in general have been “scrambled together by a combination of doing seminars, getting grants, writing books and living in a rent-controlled apartment,” and cheerfully admits his film isn’t likely to open widely in the multiplexes of the country any time soon. “It’s feature-length but not a feature film—there’s no narrative trajectory. It’s hard to carry around something long, ‘difficult’ and ‘experimental.’ To the extent that I can do it, I become my own distribution company, sending out duplicates to festivals and taking the film places. It’s trundling out into the marketplace at its own steam. One imagines that movies are fixed objects, but I’ve found that it looks different in different places. In experimental festivals it looks mainstream, yet at conventional festivals it seems transgressive. Film itself is interesting. It’s a living, breathing thing. Our experience of watching is really watching the process of film dying.”

To: Ken Anderlini, Programmer, Vancouver Film Festival

From: Mike Hoolboom

Hi Ken. So sorry I can’t step on the airplane tomorrow and come and see you and live inside the festival. Spoke with your assistant yesterday who said she’d pass on word of my not coming. Earle Peach composed most of the music, as well as doing the soundwork/mixes for the film, and am hoping he’ll show. He lives in Vancouver. Had also hoped, to make up for my absence, that you might be able to read out the following as an intro to Panic Bodies before each of its two screenings. Here goes:

Big hugs to Ken for taking my film so late and to all of you for coming. Sorry I couldn’t be here to speak with you. I’ve been sick, mostly, this past month, remembering again the link between illness and movies—both are mediums which make certain expressions possible, others impossible. Both are communicated, usually, in public, though they are understood, and most deeply felt, in private.

The film you’re about to see was conceived in illness.

There are folks much stronger and nobler than I who do other things: like work at a food bank or retreat into Zen monasteries. But as a child of network televison, I’m too lazy, instead I get sick. Through my illness the chatter of small voices and small duties manage to leave me at last, and I am transported from my world of daily banalities into another one, the real world, whose incandescence I manage to dull eventually with habit.

Panic Bodies is a film that has taken the shape of a body or a house, it exists in many parts which don’t resemble one another. The bathroom, for instance, doesn’t look like the kitchen. The first room you’ll encounter features a kind of buffet. And maybe it’s true what they say, that the mouth is a wiser organ than the eye. Because when you’re invited to a buffet dinner, you know that you’re not going to eat every last bit of food on the table. But the eye is a greedy place. It wants everything. In the first room you’ll enter, the buffet tables are full, and I worry that if you try to see everything, you might wind up catching not much at all. I would suggest instead that you make a choice, and that you be guided in your selection by the first principle which guided me in this film’s making: to move towards all that gives you pleasure.