Panic Bodies script

note: Panic Bodies is in six parts: Positiv, A Boy’s Life, Eternity, 1+1+1, Moucle’s Island, Passing On. These are texts for three of these parts.

Positiv

Last night I had this dream that I’m living in a world where there’s just two kinds of people: bodies and minds. Somewhere a bell rings and the whole world stops for recess so we all run out of school heading for the wall on the other side of the yard. I can feel my legs growing as I run and with one giant step I’m there, I’m at the wall watching everyone race towards me. And then I realize omigod, I’m a body.

Which is funny because ever since becoming HIV positive, I’ve felt like a virus that’s come to rest in this body for awhile, that it really doesn’t belong to me anymore, like I’m trying on a new suit that won’t fit. I couldn’t be the one who starts sweating at night for no reason at all until the sheets are so wet I have to ring them out in the morning, or the yeast in my mouth is so bad it turns all my favourite foods, even chocolate-chocolate-chip ice cream, into a dull metallic taste like licking a crowbar. I know then that my body, my real body is somewhere else, bungee jumping into mine shafts stuffed with chocolate wafers and whipped cream and blueberry pie and just having a good time, you know?

There are days I wander through the streets like Michael Jackson, deciding to have that one’s nose, those lips and my waiter’s perfect clam shaped ears. When I look around my apartment I think that everything has a warranty except my body, everything here can be replaced or traded in except for the cellulite army which has conquered my thighs, or the small hands which were always too clumsy to play Satie. When I was six and learning the scales I watered my hands everyday without result, until I realized that despite all the chaos and upsets and frustrations my life possessed a shape after all, a unity of design, and that shape was my body.

You’ve grown apart from your family, you remember the day you decided to hitchhike to Vancouver with a large cardboard sign and a backpack filled with books and candles. Your mother drove you to the end of town saying that’s it, you can’t come back now, good luck. That was the day you left home, crouched in the cab of a Molson’s Brewery truck headed for Kapaskasing. Since becoming positive the war of silence has been called to a halt, the arguments dissolved beneath the sense that there’s no longer time for that now. You are haunted by the image of your own infirmity, bedridden and helpless, that you would once again become a child. This nightmare of dependency, of having to give yourself over to them once again, has kept you from them all these years, and now, strangely, through the agency of this disease, you’ve managed to return there, to the place where memory comes from, to the history of your failures, in the body of the family.

When I was six or seven my brother David got it into his head that if we could grow a third arm we’d be right for life, and for weeks we’d argue about where to put it. Dave figured it should come straight out of his chest for the surprise knock out punch while I thought it should run out of my butt because furniture was going to be extinct. I thought it would just die out as we got older and that I’d want something to sit on. We made a little lotion out of eggs and arm hair and a little blood and every day we’d rub it into the spot where we wanted our new limb to grow. We never did grow that extra arm—but Dave did have three nipples—just like Goldfinger in James Bond. I guess it’s not that unusual. But Dave always said that was the beginning of his double that he was growing from the chest out. He always kept a bandage over it so no one would know, one day his double would appear in the world to take his place and he could get on with his real business, or maybe, he’d wink at me, maybe he was already gone.

I think I always looked up to Dave a little bit—even during that year when he was painting everyone’s car green, it just seemed like the most obvious thing in the world. Dave said that next to the brain, the smartest part of a guy’s body was the balls because they were all wrinkled and veiny like the brain was—only there were two of them —and after jerking off into a petri dish he would study his cum for omens. If it came from his left ball then it was about the past, and if it was from his right ball it was about the future. He wanted me to try it, figuring the more samples he had the more he’d understand, but I was worried he’d mess up the changes going on in my body, that I’d never grow up. Or that somehow, through his experiments, I’d become more and more like him as I got older. And I guess that scared me some.

He was the first one who was told you were sick, and you’d never seen him cry before, not since he was six or seven and that was just because he caught his hand in the door. As you held each other and whispered I love you, you knew why it had taken so long to tell him. Your sickness was real now, because it lived independently of you. From now on it would live in your brother as a reminder that we would never be young again, never young enough to change what had already happened. Before you spoke your illness was a professional concern discussed with the doctor, drawn up in charts and tables. If your body had become a danger in your sexual relations, with Dave it had become again a house, a place where blood was thicker than the years we’d grown apart, a place where the certainty of death was no longer disguised by our youth.

There’s not much the doctors can do for you, except draw this blood out for tests. In fact, the more your condition worsens, the more tests are demanded, as they seek ever finer ways to monitor your decline. Your identity is clinging to these numbers, your CD4 counts, the ratios of enzymes and tissues which continue to betray you. At night, when you’re alone, you try to visualize them, you try to imagine them as part of you, belonging somehow, but find that you can’t. The disease seems always separate, an invader, and you wonder whether this lack of imagination will finally prove fatal. Because you’re unable to embrace this intruder, it has no choice but to destroy you. You imagine your body as a military map, with arrows marking movements of troops and tanks, each constellation of borders remarking some lost bottle. As you turn the globe between your fingers it comes to you: the division of geography into nations is also a map of the dead world, each line signaling a procession of corpses. Because the number of the dead far outweigh the number of the living, we’ve divided the world into nationalities in order to mourn it more perfectly. And our mourning together, this must be the thing we call a country.

You think: it’s hardest for your friends, when they met you for the first time there was no way to know that they would have to bury you one day. You all seemed so young, and while they’ve continued to age at the usual rate, all of a sudden you’ve grown so very old, so close to the time of your ending. Mostly you would like to apologize for asking so much of them. Because your slide into sickness is slow, monitored by the machines at the hospital, you don’t notice at first that you’re any different than you ever were, until they come to visit. And while they are gracious and kind and you love them so much, you read the whole cruel truth on their face. You watch yourself dying there. This look hurts you more than all the fevers and sweats and blind panics because where once there was love, now there is only fear, and this vague, terrible sense that all this could have been avoided if only you’d been a little more careful, that somehow you did this to hurt them, or that they weren’t enough so you had to go out and get more, and after you crossed that line you were never the same.

Now that I have AIDS I keep tripping over myself, and sometimes when I’m talking with a friend I’ll just nod right out. When I come to they have this terrible expression on their face like, “Are you alright?” and of course I am. I’m fine, I’ve always been fine, only they can’t see that. My body keeps getting in the way.

Last week Donna came to visit, my best friend. She told me that 6,000 cells die in the body every day and that every seven years we’re completely new people. Donna’s always coming up with crazy shit like that. So I guess I just have to wait it out. I think I’m gonna remake myself as a fat ice cream queen with perfect skin. Donna says that sounds just perfect and then she kisses me because it’s time to go. Visiting hours are over.

Eternity (this text appears onscreen)

Dear Ed,

Hoped I would hear from you but then,

I said I would call if you didn’t,

so I probably will.

You sounded a little tired and said

you had been ‘up and down’,

so I worry that you’ve had

fluctuating health.

You had written about starting

pentamadine treatments

and I remember Ken

(who had them from early on after his diagnosis)

told me that the infusion was unpleasant

and often followed by nausea.

He did say there was

less of a reaction after the first month.

My own nausea-producing medicine

(sinemet) has been altered

to a time-release prescription

which is less irritating

because not as much enters my system

at one time,

however, it is not always 100% effective

until the next dose.

I’m less in touch with it at present

but I remember that in connection with the light

I had that near-death experience

you know, the one of going into the light

and presences being there on the way.

All sound and light were there

as I drifted into it

fragments of voices and sounds

and people were present

and if I let go and passed into it,

the light and sound would gather into a single sound

like a heavenly choir.

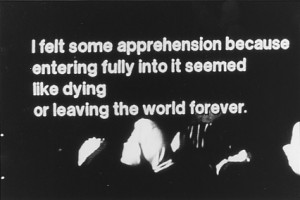

I felt some apprehension because

entering fully into it seemed like dying

or leaving the world forever.

Then just at the last,

concern for someone I knew

pulled me back

and I wondered if it were possible to go into the light

and still be in the world.

It began like a dim star

in the very center of the darkness.

I had seen it many times

while meditating

Sometimes it was blue or red

or outlined by halos of changing colour

and sometimes it took forms

which I came to feel

were projections of my mind.

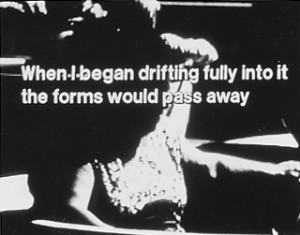

When I began drifting fully into it

the forms would pass away.

It seemed like the sounds and voices created there

were the result of the mind’s attachment

to worldly things.

This primal light and sound

felt like home, it was the place

my personality drew from

to create experience.

Some would say that this feeling

is the last stimulation of the phosphenes

(that are credited with stimulating dreams)

as the brain shuts down in death

and the ringing sound is a similar

last vestige of hearing

when outside stimuli are shutting off.

I don’t know.

I also talked to my brother about this

when I arrived at the hospital

the day he died.

He was unconscious

and in intensive care on a respirator.

The hospital staff said

he had reached the point

where they suspended the rules

about only one person at a time visiting

and they encouraged us to talk to him

because they said patients seemed to hear

although they might not respond

and that voices of loved ones sometimes

brought them back

when nothing could be done medically.

I told him many things

but then began to remind him of our talks

about the light.

I asked him if he could see the light

and told him he could go into it.

I told him he could swim back to the shore

where I was

and Howard and Andy and Andy’s friend Peter

(who came to show Ken

his new green-dyed mohawk haircut)

I told him I wanted to show him

some old photographs from when we were children

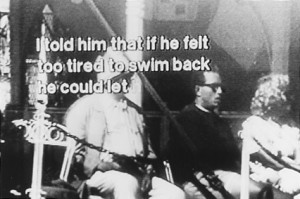

but I told him that if he felt too tired to swim back

he could let himself drift into the light.

I stroked his arm while I spoke.

His pulse raised once

while I was stroking his arm.

But later I was told that he had been

administered a stimulant to start his pulse up again

and that when it only perked momentarily

the doctors knew he was probably going to slip away.

Everything in this world is constantly changing.

Eventually everything is gone or not what it was.

Our attachment to it causes pain and joy

satisfaction and frustration.

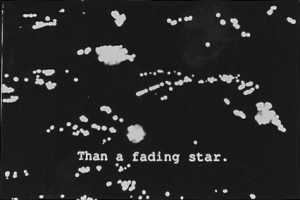

The light and the sound have a feeling of eternity

but they may just be the dot on the tv screen

when it’s turned off

fading away.

Practicing at non-attachment

is a preparation to deal

with the gradual loss of everything.

I write this as one who cried

and wailed with grief

at the death of my cat Spider.

I am writing these thoughts because they

relate to that moment in my kitchen

when we speak, and what happens to us.

Hope to talk with you soon

and that you’re feeling a bit better.

All my love,

Tom

Passing On voice-over script

When we were little, maybe six or seven, my brother and I would get up in the middle of the night and sneak downstairs so we could watch the midnight mysteries on television. It sounds funny to say now but we loved to watch people dying. In the daytime we’d practice for hours on the front lawn, trying to get it right, crawling and gasping our way towards a perfect close until our mother would call us, embarrassed that the neighbours might see. But every night, as we watched the tube, we knew that the secret we shared with broadcast television was that it was preparing us for our own end, that even as children we were already growing older, already dying.

These are pictures of Aunt Harry and Phil Jackson. He was the only adult we called by his first name, and somehow that made him even more special, like it was alright to say the name of God. Phil worked at the steel plant like just about everybody else then, and he did alright until he slipped on a bin and caught his hand on a flywheel. He wasn’t much good for the company after that. They used to go camping up north every summer, but after the accident it was all they could do to keep their house together. Phil didn’t really remember the accident much, he always said, it just happened that’s all, but one day he went out for a paper and never came back. He just vanished into thin air.

Words were a luxury, an indulgence I never shared with my brother, so as we grew older we tried to find something to put in its place. We tried bowling, fortune telling and board games before beginning again our mad pursuit of the road. Somehow it was while driving that we could raise again the possibilities of home, rushing from the judgements that words always seemed to bring us. Here, in the car’s restless overturning of geography, we could find a communion of escape where we might be able to leave behind, if only for an afternoon, the long years apart, the vanishing trail of letters and photographs that only seemed to lead us further from home, and from each other.

Olson wrote him that the body was just a bag of water tied together with a fig leaf. This conspiracy of chromosomes we call the family, a nose or knee joint borne for generations, ensured that he would always be a part of the past without being able to remember it, because there was no way to go back. He wonders how many others have shared his favourite colour, his birthdate, the quick tempers and arguments unchanged for centuries except for the patterns on the wallpaper. It seems no matter how far he ventures he carries always this uniform of recall, this habit of memory we call the body.

His recollections, his memory ensure that he is never finally alone, that he is always in the middle of a crowd scene, trying always to answer the call of his body, of history.

When he is thirteen he travels with his father to Sudbury. His first time away from home. Normally, his father never leaves the big upholstered chair in the living room, the endless repetition of his work day repeated here in his terrible longing to become the furniture which surrounded him. When a letter came announcing his father’s stroke we grimly headed north, and it seemed to me the first time I had ever seen him out of doors, like an animal. Pushing through the crowds of the bus terminal he seemed shrunken somehow, just another man with a coat from the Eaton’s catalogue. When we arrive we go to the hospital where an older version of my father lies beneath a forest of tubes and machines. Sometimes, when I look very hard, I think I can see the old man’s cheek move, but I’m not sure, and after a few minutes my father motions to me. It’s time to go.

When he is sixteen he meets his aunt for the first time, Aunt Leah from Rio de Janeiro. She wears brightly coloured scarves and long dresses with pictures on them, and greets him with a long kiss and a hug, as if they were lovers rejoined after the war. It’s the first time he has ever kissed a woman. The next day she takes them for a walk, the two brothers, past the Harley shop and the Burger Queen and the statue of the mayor with his head cut off. Every time they spot an ice cream stand she stops and buys them one, so this is how they reclaim the neighborhood, floating in the cool dreams of Mr. Sno-Dip and Mr. Softie, wandering through a town they’d lived in all their lives as if they’d never seen it before. Explorers of a brave new world fueled by ice cream and this inscrutable stranger. It’s only when they lean together, his mother and her sister, that he can see they’re related at all. For all of his mother’s stubborn determination to make it in the new world, her sister seems the road not taken. She has a lightness somehow, as if the steps she made left no impression, managed to disturb nothing in her passing. On the last day she draws him aside, insisting that she has a secret to share with him. “Never get old,” she whispers, and then she is gone, managing to take even the smell of her perfume with her onto the airplane.

As I grow older there is less television and more funerals. Eva, Jonson, Mary, Rashid, none of you have managed to survive, and as I am also growing older it’s more difficult to lift you from the ground. Every day it seems easier to lie again beside you, to fall into arms which seem more familiar in death than those who would embrace me here, in the kingdom of ghosts, all of us haunted by what we may become. We the living are the ones left behind, the ones who have come after, left to wonder if a lifetime is time enough to remember all who have passed away. Is there a smile we are capable of sharing, or an intimacy we might reveal that has not already been offered? Our skin is a blanket passed on from one decade to the next, a quilt in which the destinies of the past have crafted an indelible design. If we are condemned to repeat, is it only so that we could come to know you more completely, our dead brothers and sisters? Do the contours of our flesh reveal, in its collection of pores and tissues, the shape of history, or only its pressures, as we step quietly towards the grave, where we can rejoin the multitudes of the lost, the buried and the forgotten.