Letters From Home 15 minutes, 16 mm, 1996

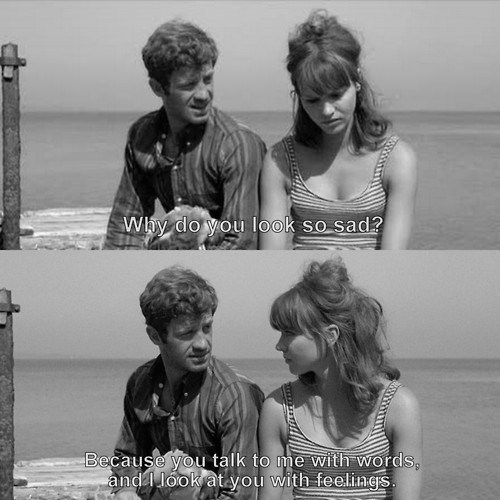

Begun with a speech by Vito Russo, Letters invites a chorus of speakers to sound off on AIDS, love and death. Impelled by a variety of formal procedures, this series of mini-portraits are generously furnished with found footage extracts, hand-processed dilemmas, home movies, super-8 psychodramas, pixilated phantasms, intergalactic warfare and a hot kiss in a cool shower.

“For a work which transforms and transcends the essay film, for its stunning vision and intensely moving testimony of life in the age of AIDS, the 1996 NFB-John Spotton Award goes to Mike Hoolboom’s Letters From Home.” Toronto International Festival Short Film Jury

“Mike Hoolboom has produced an absolutely sensational work, not only by the extreme density and intelligence of the witnesses who appear in the film, but also by the visual quality and inventiveness of his cinematographic language. Each shot, each edit has a message of pure aesthetics in this film. An overwhelming and luminescent reflection on death, AIDS and the living. Fifteen minutes to live!” Image and Nation Catalogue, Montreal

“An overwhelming and luminescent reflection on death, AIDS and living, Letters From Home is a compelling montage of mini-portraits intercut with found footage, home movies, super-8 dramas.” Sheffield International Documentary Festival

“Letters From Home is an impassioned investigation of the politics of disease. It is also something more. If a full comprehension of life including the recognition of death’s constant presence, even in our death-denying culture, Letters offers a cogent, courageous rendering of this notion. It also demonstrates again that the penetrating and poignant films of Mike Hoolboom comprise one of Canadian cinema’s most compelling illuminations of those ephemeral outlines of perception we call life and death.” Tom McSorley, Take One

“The future is not what it used to be””and in this intensely lyrical award-winning work Mike Hoolboom tells us why by creating a dialogue between himself and the late, great Vito Russo. It is both a testimony to life in the age of AIDS and a call to smash the stereotypes that threaten to ghettoize this plague.” Inside Out Festival

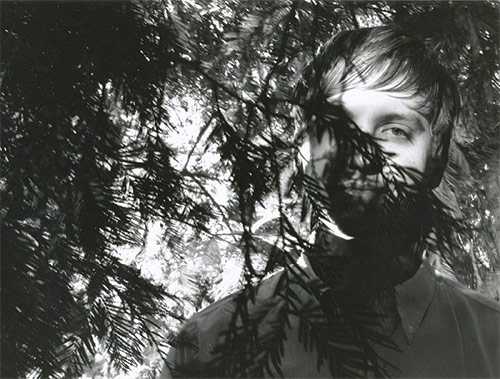

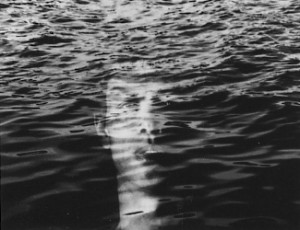

“A visual elegy, a sepia mosaic of images and faces, a shattered dream, a battle… Here, in a few words, are some of the things evoked by Mike Hoolboom’s film Letters From Home. Not forgetting AIDS, of course – the central theme. A unique account gradually takes shape through several different voices. Many and varied are the dreams, memories, fears, thoughts and revolts that the illness provokes and which emanate from the individual and the collective. In the images that follow, the fragile material captured on film forms a muted and painful lament. They evoke childhood, loves, struggles and doubts. Daringly and unexpectedly juxtaposed, they sometimes raise a smile. They are the tragi-comic archives of men desperately trying to free themselves from the laws of gravity, accompanied by the soft, nostalgic crooning of Billie Holiday. The images of a bride in her wedding dress, running alone. Some of the sequences play upon a delicious asynchronism with the voices off-camera, or else illustrate them evasively. Little by little the film reveals its complexity, but it is capable of changing its rhythm, slowing down or accelerating, then concentrating on a face, leaving aside the special effects and superimpositions in order to simply listen, allowing a deep emotion to emerge. For the experimental nature of Mike Hoolboom’s work never intrudes upon the concrete, personal words of these letters, which also suffuse a ray of hope. Despite the everyday reality of rejection. Here the stricken are no longer nameless strangers, they are acquaintances, friends, loved ones.” Bertrand Bacqué, Visions du Reel

“Letters From Home is an intensely moving testimony of life in the age of AIDS. A speech by Vito Russo, in which he suggests that we all live with AIDS whether we are infected or not, is divided into a diaspora of texts read by many different people. Hoolboom adds his own narrative of seropositivity marking the discontinuity of his voice and the others’ through a montage of found footage and portraits.” Hot Docs Festival, 1997

Loving a Disappearing Image by Laura Marks (excerpt)

… Many recent experimental film and videos, flouting the maximization of the visible that usually characterizes their media, are presenting a diminished visibility: their images are, quite simply, hard to see. In some cases this diminished visibility is a reflection upon the deterioration that occurs when film and videotape age. Interestingly, a number of these same works also deal with the loss of coherence of the human body, as with AIDS and other diseases. The following essay continues my research into haptic, or tactile, visuality, here to ask what are the consequences for dying images and images of death, when the locus of identification and subjectivity is shifted from the human figure to an image dispersed across the surface of the screen. In defining a look tied to new ways of experiencing death, these works appeal to a form of subjectivity that is dispersed in terms of ego-identity and yet embodied physically. What this look enacts is something like a perpetual mourning, something like melancholia in its refusal to have done with death. Ultimately, it cannot be described by these Freudian terms. These images appeal to a look that does not recoil from death but acknowledges death as part of our being. Faded films, decaying videotapes, projected videos that flaunt their tenuous connection to the reality they index, all appeal to a look and loss. There are many ways that the visual coherence and plenitude of the image can be denied to the viewer. Among these are the ways films and tapes physically break down, so that to watch a film or video is to witness its slow death. Another is the way significance relies not upon the viewer’s ability to identify signs, but in a dispersion of the viewer’s look across the surface of the image…

I began this research contemplating the conundrum of having a body that is not one’s own, a betraying, disintegrating body. A body that slowly or quickly becomes other, at least insofar as one’s identity is premised on wholeness. This happens with all of us as we age, and it happens acceleratedly for people who have AIDS or other diseases that invade and redefine their bodies. In Letters From Home, Mike Hoolboom expresses the paradox of having a body that is yours but not, when a character relates a dream that he was taken to a room where a handful of crystals was spilled on a table, each of which, he realized, represented an aspect of his personality. “There was my love of the screwdriver and the universal wrench; the break with my sister; my weakness for men in hairpieces.” The man displaying these crystals to him becomes a doctor and tells him he is HIV-positive. “And sure enough, he pointed to an off-colour stone that was slowly wearing down everything around it.” To have an aging body, as we all do, raises the question of why we are compelled to identify with images of wholeness, as classical film theory would have it’ the question of whether this still is or need by the case; and the question of what it would be like to identify with an image that is disintegrating. Following Vivian Sobchack (1992), I suggest that identification is a bodily relationship with the screen; thus when we witness a disappearing image we may respond with a sense of our own disappearance. Cinema disappears as we watch, and indeed as we do not watch, slowly deteriorating in its cans and demagnetizing in its cases. Film and video, due to their physical nature, disintegrate in front of our eyes: a condition that archivists and teachers are in a special position to mourn. When I open the can of a colour film that has not been viewed in twenty years, the thrill of rediscovery these patiently waiting images is tempered by their sad condition, once-differentiated hues now a uniformly muddy pinkish brown. When I watch an analog tape from the early days of video experimentation, the image appears to have lifted off in strips. The less important the film or tape (and by extension, its potential audience) was considered, the less likely that it will have been archived with care, and thus the more likely it is that the rediscovery of the object will be such a bittersweet pleasure. These expected and unexpected disasters remind us that our mechanical reproduced media are indeed unique.

When I began to teach film studies I realized that the students will never “really see” a film in class: it’s always a film that’s half-disappeared, or a projected video that just teases us, with its stripes of pastel colour, that there might be an image in there somewhere, that there once was indexical; relationship to real things, real bodies. One response to this situation can be to see the actual, physical film or video we see as a mnemonic for the ideal film, the Platonic film, once seen in 35mm in a good theatre. This seems to be Seth Feldman’s (1996) argument in What Was Cinema? , in which he suggests melancholically that the institution of “cinema” has ceased to exist, given that most film viewing experiences occur through the medium of video, at home or projected, and will increasingly take place through digital media. A notion of the ideal film, which our viewing experiences can only approximate, is also the basis of Paolo Cherchi Usai’s (1988) thoughtful argument that cinema history would not be possible without the disappearance of its object …

Oh God please not that. Not AIDS. Again and again. The news cycle, the sound bites, the headlined pundits have all weighed in, and surely that old question can’t be still doing the rounds, can it? And yet. The past isn’t what it used to be. I made this movie as a sound/picture virus that might enter its audience, and turn them into us. Oh yes, I imagined, we’re all in it together now. Let me project my feelings until they become your feelings, let them enter you, become you, spreading until there is no escape. After the death of her brother, Diamanda Galas had his epitaph scrawled across her knuckles: We are all HIV positive.

Letters From Home offers a virtual community, a collection of friends and familiars who all take up the stump speech: how do we speak AIDS, live AIDS, in the small large places between us. It was made in the moments after the cocktail arrived and delivered us from a certain end, or at least the us that lived in first person health carings, which left the chosen fortunate few with the newly difficult task of having to go on when every moment had been pointing in the other direction. Is it too awful to say that I was disappointed, confused (why me?), angry (why not also them?), sad beyond measure? Life after death has been more and less than I imagined. Only in the last year two friends confessed to me that they had secretly hoped that I would infect them with the virus, and that we could die together. How much older we were then.

Beyond the Fringe: Letters from Home by Noreen Golfman (Canadian Art, 1986)

For at least a decade now, artist and filmmakers have been trying to make films about AIDS. Born into an image-soaked era, AIDS has taken naturally to film as a host site for feature-length narratives. But no made-for TV movie or theatrical feature film has quite caught the complex of panic, fear, denial and ignorance that attends the disease as powerfully as Mike Hoolboom’s Letters From Home. In this award-winning filim Hoolboom manages to capture in fifteen gorgeously explosive minutes what so many sentimental morality plays have failed to convey: the racking frustrations of being HIV positive and the persistent social confusion surrounding the affliction.

Letters From Home belongs to the growing rich repertoire of short experimental films that continue to be produced in this country in spite of and against full-length mainstream works. Hoolboom himself prefers the term “fringe” both to mark the subversive nature of his art and to avoid the trap of generic dismissal. “Experimental” is too convenient a term to describe a vaguely defined genre of unconventional styles, not to mention any product running under the standard ninety or sixty minute lengths. What, then, do you call a decidedly political fifteen minute film about AIDS that refuses to adhere to common aesthetic practices? “Avant-garde” respect the edge of inquiry and confrontation for which the film aims, but that term too, like so many with early modern ache, ahs lost much of its linguistic power in the diluting wishy-wash of postmodern inclusivity.. If we have come to a wide understanding of what we mean by “fringe theatre”- alternative, oppositional, different – why not “fringe film?”

As the title Letters From Home indicates, this is an autobiographical piece. The question of labels seems especially important. Letters from Home is, among other things, a personal cry of resistance against social acts of containment, especially those that brand and stigmatize. Being HIV-positive surely changes everything-everything being identity. Hoolboom, who discovered that he had the disease in the 1980s, after he had already made a number of short and provocative films, is plainly positioned in opposition to and on the margins of healthy society. Marked by such difference, the body is free to speak its mind. Full-length features presume to have al the time in the world; short fringe films must speak with an urgent burst of declarative power. Hoolboom’s elaborately fragmented style of filmmaking, complexly textured and aggressively layered, shatters all suspicions of order and certainty. In his hands, this short non-genre, working to place matters under compression, refuses to be absorbed into the mainstream vernacular. To put it plainly, the body of the film comes to represent the body of the man.

What, then, is this body? Well, it is both whole and in pieces, a series of allusive and enigmatic images underscored by fragments of song and text. Threading through these disparate representations of culture, identity and experience are voice-over readings from a 1988 speech by the late AIDS activist Vito Russo. At once cogent, angry and courageous, these epigrammatic passages carry the enormous weight of death about them, but in their performance we hear a wild defiance. A descriptive inventory of the accompanying images scarcely conveys the film’s fluid play or irony and grace: home-movie segments of a smiling child at play intercut with archival footage of exploding warships, makeshift planes and ancient automobiles; ghostly shots of civic spaces, bleached of colour and stripped of emphasis, overlap with silent bursts of flame suggesting Armageddon. If, as the film announces, “living with AIDS is like living through a war,” where is there evidence around us of the fight for research and drugs to relieve the dying? This question hauntingly informs the film, but it does not preclude the personal struggle to inhabit the fullness of life, enjoy moments of being and pleasure. Discernibly slowed-down, scratched and tainted shots of men making love under a wash of shower water assert a primal bliss that might be the cause of death itself. Each set of images bears traces not only of its own creation and selection but of its own vulnerability, trapped in time and yellowing away, but purged of nostalgia for which one requires the privilege of health.

Letters From Home adds up to a strange force of immediacy. With neither the dead end of closure or the certainty of duration, the film leaves the viewer with an odd rush of possibility, perhaps the urge to act up. This is no small thing, however short the piece. But, of course, to see it is to know what all this means.

Hoolboom has been amazingly prolific in the 1990s, making internationally acclaimed films-over fourty shorts and features (Kanada, Valentine’s Day, House of Pain, Carnival) with a fury to match his cinematic disobedience. It is unlikely that many Canadians will see his work any more than many will come to understand the politics of AIDS. One of the inspired observations in this film is that our understanding of the disease is almost entirely mediated and thereby misrepresented, a condition that leads to a wide intolerance born of fear. Paradoxically this short, frayed film attempts to destroy its own images to assert their power. There is nothing linear, straight forward, neat or untroubling about living with HIV and, as Letters From Home insolently demonstrates by example, no body of film can hope to do justice to such a condition by pretending that there is.”

Introduction

Introduction to Letter from Home, made at VIHsibilite, a day-long conference on AIDS, testimony and the media, held at the Universite du Quebec a Montreal on December 11, 2009. I whispered this text into the ear of luminous Concordia professor and writer Thomas Waugh, who provided simultaneous French translation.

21 years ago I had a dream

that the angel of Montreal came to see me.

She was whispering in my ear

and I was very surprised

because she was speaking French

and I could understand her!

She said I have some good news and some bad news.

The bad news is that you’re HIV positive.

The good news?

Even though you don’t believe me now,

it will be the best thing that has ever happened to you.

Ten years ago she came to see me again.

She said that this condition is a crisis, which is also an opportunity.

A crisis of intimacy, an opportunity of intimacy.

Please, she urged me, it’s time to make your first movie

in close-up.

It may look dated one day

scratched and old fashioned.

But let it testify to a moment,

the hope of this moment

that I’m sharing with you right now

my love.